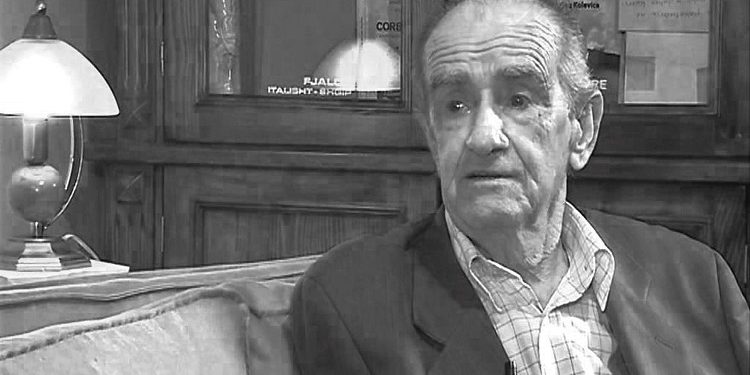

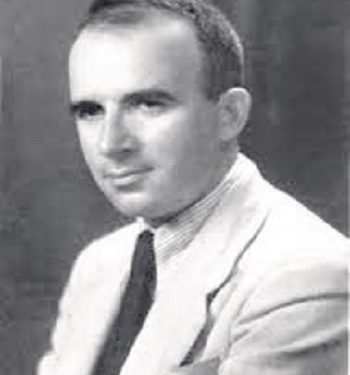

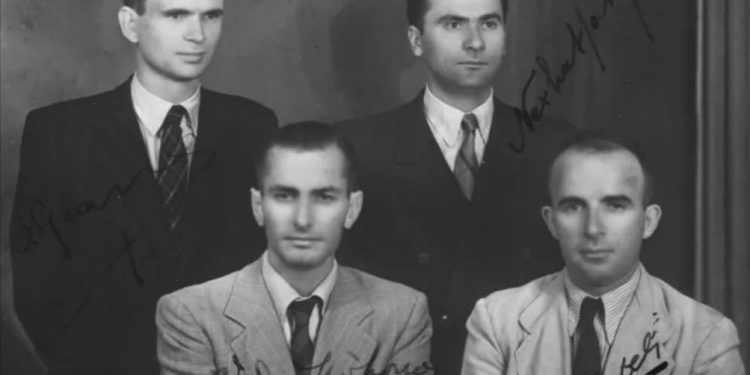

Memorie.al / I shared a friendship with Mitrush Kuteli that lasted almost a decade (1958 – 1967). He – a renowned master in his mature years. I – a young engineer chasing the muses, whom he, with his expansive heart, always uplifted and placed by his side as a peer…! I visited Mitrush often because there – as Lumo Skëndo says of Naim – “I would arrive poor and leave rich; I would arrive hungry and leave satiated; I would arrive hopeless and leave full of hope; I would arrive with a sick soul and leave feeling alive and spirited.”

But today, on the anniversary of his birth, what more can I say than what I have said before and what so many others have said? Nevertheless, for the greats, there is always something left to tell: In those twenty or so years of life spent under the communist dictatorship in Albania, Mitrush Kuteli occupied himself (out of necessity, not desire) primarily with translation; therefore, I wish to say something more about his contribution to this field.

The Translator

As early as May 1939, he was the first to introduce the Albanian reader to Romania’s great national poet, Mihail Eminescu, publishing a book of 24 poems translated by him, along with a description of the poet’s creativity and biography, where he had the courage to defend the idea – somewhat argued – of the Romanian colossus’s Albanian origin, from whom he had translated and published his first poem at the age of twenty-two.

Four years later, through the flames of the Second World War and his own bitter experience in that war, he was the first to introduce the Albanian reader to the great poet of Ukraine, Taras Shevchenko. To this period belong his precious observations on the accuracy and value of translations, as well as on the purity of the Albanian language. Sixty years separate us from these words spoken by him, but it seems to me they are even more valuable today. Listen to them:

-“We must say that we need shqipërime (Albanian adaptations), not word-for-word translations. Those who wish to enrich Albanian with the masterpieces of world literature must choose the former path and not the latter.”

-“(In translations) we have impoverished pens and, especially, anonymous scribblers who did not know the laws of Albanian and, many times, not even the language from which the work originates. Many translations, where Albanian has emerged slaughtered by the finger.”

-“And I would pray to those who make laws to add a new paragraph to the Penal Code for the punishment of all those who, because they possess a typewriter and a Greek or Italian translation made from a French text, mock Albanian and the Albanian reader.”

-“The press has a heavy mission and a responsibility in relation to this mission. Otherwise, the press, the editor, becomes responsible alongside the translator as destroyers of the language.”

Upon these clear and sound principles, he based his work as a translator from early on until the end, and with everything that left his hand, he gave us unattainable examples of dedication and high quality. This is entirely natural, because he who has proven himself with first-class original works cannot dirty his hand by making poor translations. There is also something unique here.

As is known, throughout the “socialist camp” of that time, when the glaciers of the communist dictatorship set in, some talented writers did not make a pact with the devil but found refuge in translations and writings for children. Thus, for example, in Russia, Samuil Marshak translated Robert Burns and other writers and wrote charming pieces for children. Valery Bryusov translated classical Armenian poetry. Boris Pasternak, while working secretly on his Zhivago, translated the second part – so difficult – of J.W. Goethe’s Faust and parts of Shakespeare.

And with us, the writers who had produced original works before the war and had made a name for themselves, after surviving the Xoxe typhoon, also found refuge in translations and children’s stories. Lasgush performed the colossal work of translating Eugene Onegin and all those poems by Heine, Goethe, Mickiewicz, Burns, etc. Mitrush Kuteli did the translations we will discuss below. Here I want to point out something important that shows how much harsher the dictatorship was here and how much more savage was the envy, ambition, and even malice of colleagues.

In Russia – that is, in the former Soviet Union – V. Bryusov, S. Marshak, and B. Pasternak received the highest awards of the time in their country for the translations they did.

With us, not a single award was given to any of that distinguished generation of translators who were the sole pillars holding up Albanian culture. Not then while alive, nor today after death. Mitrush Kuteli – having emerged after two years of heavy imprisonment, unaccepted, even expelled as an economist, insulted, despised, and mocked as a writer – how was he to earn his daily bread for himself and those he carried on his back, this knower of several foreign languages? Nothing remained but the wide field of translation!

And Mitrush Kuteli, with the heavy yoke of the quota of that time, for fifteen years in a row (1952–1967), cultivated and plowed the endless chernozem (black soil) of translations. From Russian, he translated over twenty volumes; from Romanian, four or five volumes; he translated several volumes of Turkish, Chinese, Persian, Arabic, Mongolian, and Polish prose; he collected and translated folktales of various peoples as well as the poetry of Eluard and Pablo Neruda (the volume “Wake up, Lumberjack”). This entire amount to over seven thousand pages of books printed in small type.

We must not forget, however, that during this time, he also produced books with original writings acceptable for that time, such as “The Chestnut Forest,” “Xinxifilloja,” “Ancient Albanian Tales,” and “In a Corner of Lower Illyria,” and the unpublished poem “The Rivers Flow,” which together make more than a thousand pages. Anyone can understand from these few dry figures what heavy work that so sickly man performed!

Everyone has spoken and speaks with admiration about the high quality of Mitrush Kuteli’s translations, especially about the translation of the book Dead Souls by N. Gogol, but a genuine study has yet to be done. Albanian culture owes a debt here, just as it does for the lack of a study on the evaluation or importance of the seventeen books and pamphlets of economic writings by Dhimitër Pasko – the economist. Who knows, perhaps someone from the Faculty of Economic Sciences at the University of Tirana is listening.

Dhimitër Pasko (Mitrush Kuteli) was a distinguished economist, a rare translator, but above all, he will remain as an Albanian writer in one of the highest places of honor in Albanian literature, a unique master of prose and the Albanian word.

To Mitrush, for that peerless inspiration with a deeply Albanian soul in his writings, we can say it was fitting, as for no other among our writers, to repeat the words of the great Frenchman Pierre-Jean de Béranger:

“Le peuple c’est ma muse” (The people are my muse).

And because the people were his muse, he is read and will be read with pleasure by simple folk, by high intellectuals, and by cold scientists, and for all, he will be a bountiful mine.

The Prisoner

Much has been written about some of those Albanian men, distinguished figures of culture who were imprisoned, interned, or executed during the communist dictatorship in Albania. Many of those men had wives who silently followed them, kept them alive, went along with them, and thus, unsupported – even insulted and despised, with their husbands in prison, interned, or executed – knew how to raise and educate children for the Albania of tomorrow; and if they groaned or shed tears, no one heard or saw them. There were many such women, but it seems to me that nothing has been written about them at all. I know how to speak only about a few.

I know of a respected woman from Korça who, with two daughters not yet fully grown, went to see her innocent husband locked in the Burrel prison. And it was an Albanian who spat on them there as they waited, when he learned they were the wife and daughters of a prisoner.

It was an Albanian as well who wanted to force them out of the car and leave those defenseless beings in the middle of the crossroads, but no one could stop that soft-spoken woman from performing her duty as a worthy spouse. I also know the wife of a writer who, in early 1991, having returned straight from internment, climbed the stairs of the then-offices of the newspaper Rilindja Demokratike. No! I will never forget that face of an Albanian woman! I do not believe there is a white woman’s face in the world with so many deep lines, scars, wrinkles, and furrows – marks as ugly as they are painful, the result of her untold sufferings.

I also knew an elderly woman, may she rest in peace, renowned for her rare feminine beauty in her youth, who fell in love and married a talented young writer whom they imprisoned, and when they released him, they did not allow him to be more than a municipal house painter; yet that young bride, and later woman, never left her husband’s side, living and suffering through the darkness of that time, which even the Thousand and One Nights would not be enough to recount.

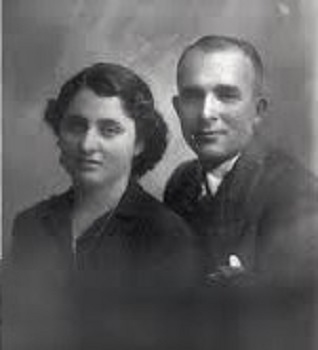

From this noble flock of silent, soft-spoken, suffering, and tireless women is also Efterpi Skendi (Pasko), the worthy spouse of the writer Dhimitër Pasko (Mitrush Kuteli). She hails from an old and well-known family in Korça, noted for their behavior, friendship, and unquestionable honesty. In the 1930s, she finished the then “citizen” school that prepared girls with education and domestic skills to be capable as worthy spouses, ladies of the house, and educated mothers who would raise refined children.

She married Dhimitër Pasko in 1946. It seems they were made for each other, because they were born on the same day of the year, September 13. This year, the 95th anniversary of Dhimitër Pasko’s (Mitrush Kuteli) birth coincides with the 81st anniversary of his respected wife, Lady Efterpi, to whom we wish a long and happy life together with her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

We said they married in 1946, but almost exactly one year after the marriage (May 16, 1947), Mitrush Kuteli was imprisoned and sent to the extermination camp of Vloçisht (in Maliq) where her father and her brother, Mr. Foqi Skendi, were also serving a baseless sentence as “rich merchants.” Mr. Foqi Skendi told me: “When they brought Mitrush, they locked him in a pigsty. That camp was a horror. In the morning – only something like tea; bread – like mud – only once a day, at noon.

We were forced to go to work running. We ran barefoot through the mud, above the knees and up to the waist. Below us, leeches sucked us; above us, mosquitoes tore at us. Dysentery took its toll. When we returned from work in the evening, we walked on hands and feet like livestock because we could no longer stand from exhaustion. A merchant from Korça, Koci Misrasi, could take no more and hanged himself.

Alfred Ashiku was beaten to death because he ate a beet he found there in the mud. Another, Niko Kirka, was left tied with barbed wire to a pole facing the sun. There they left him like Christ on the cross for two days and two nights, and we, about 1,500 prisoners, were forced to walk past him and spit on him. This was the Maliq camp.”

Through this hell passed Mitrush Kuteli as well. Seeing his hopeless state in the prison and the camp, he wrote to his wife:

“So close we are, yet so far,

I beg you, do not wait for me

Terrains of darkness surround us,

And no star shines for me.

Why should you tie your fate?

To a luckless one like me,

When you know my name was crushed

By violence and brutality?

So take the courageous step

Toward a life of joy,

And forget me here, in the grave,

Dead and uncovered.”

But Lady Efterpi, who had sound personal and tribal moral foundations, was strengthened even more by that cry of despair from her husband, and for two years straight, she followed him from prison to prison until he was released in April 1949.

After this, a time of a certain loosening began following the bloody terror of the early post-war years, and the celebration of friendship with the Soviet Union began.

Then, translators from Russian were needed, and Mitrush, having emerged alive from prison, was able to find work as a translator from this language for the propaganda articles of Soviet newspapers that the Albanian state press needed to publish.

From 1952, he began working as a translator at the “Naim Frashëri” Publishing House, but then came 1956. Movements had begun in several “People’s Democracies” of the Socialist Camp. Mitrush Kuteli’s name still appeared as an “Enemy of the People” in the old Sigurimi lists; therefore, to ensure the peace of the capital, he had to be removed with his family from Tirana, based on the hypocritical law of “Urbanization.” What the two of them suffered then was told to me by Lady Efterpi:

“As I remember, it was the month of March when a policeman came to us with a paper and said: ‘Your urbanization has come out!’ That is what they said then to those who were being expelled from the city. They told us we would go to Kavajë, but where we would stay was not specified. Our passports and what was called the ‘House Book’ were branded with the stamp A.P., meaning Enemy of the People. Dhimitri was not afraid. ‘We will go,’ he said. ‘I will not go and beg anyone.’ ‘Where will we go, man?’ I said. ‘We have three children, where will we drown them in Kavajë? Tell me where I must go and I will go myself.’

We petitioned the Prime Ministry, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but no one gave us an answer. We waited in agony. When evening fell, I would say: ‘Thank God it is night,’ and as soon as day began, I would say: ‘Oh no, what will this day be like?’ because the policeman would come and threaten us: ‘When are you going?’ One day he told us they would come to take us with a truck.

We got up at three in the morning, it was still dark, and went with all the children to my father’s house. During the day, we would circle the house and watch from a distance what was happening…!”

The story is long, but this is enough to somewhat understand the sufferings of that time. Anyway, let us say that “normal” life began.

Mitrush Kuteli worked as a translator at the Publishing House, along with that flock of distinguished translators whom Lasgush painfully called the “Porter-Translators.” With the exhausting work of a translator, for seventeen years in a row, Mitrush Kuteli earned the children’s bread, but Efterpi always stood by his side. Until the daughters grew up, she alone washed, cleaned, swept, and kept the house shining. “This house,” Mitrush often said, “is held together by Efterpi’s fingernails.”

In that small kitchen of theirs, I saw for myself how Efterpi, from her place by the machine where she sewed everything needed for the house and the children, followed with attention the stew boiling on the stove. When she finished with these two tasks, she would turn her chair toward the table where the typewriter was and begin typing the translations prepared by Mitrush, so that she too could earn a few more lek for the seven mouths of that family. After Mitrush’s premature death, she worked for several years as a typist to earn bread for the children who were not yet grown.

The Commemoration

Everyone today commemorates W. Shakespeare with admiration, but it was not always so. When he emerged from the “Globe” theater, it was hard to find anyone to tip their hat in honor. And so it was for a long time…! It was Victor Hugo who said: “W. Shakespeare does not need a monument. England needs his monument!”

Taking a cue from the words of the great Victor Hugo, we say: “Mitrush Kuteli does not need a monument. Albania, Kosovo, and even more so Pogradec, need his monument. If everyone turns a deaf ear, then shame on them!”

Mitrush will be here, in Tirana, he will walk the streets in the rain and sing:

“Oh, what a wonder,

To wish not to be human

And to envy the stones

For stones do not suffer when it rains

Over Tirana.”

He will be in Pogradec, in that burnt plot of the house, raising the goblet of glory full with that harsh juice of the village that drinks the rakia.

Izedin Jashar Kutrulia will be forever in Prizren and everywhere in Kosovo, in the midst of the living and the dead. Memorie.al