Memorie.al / The Konçi family is a well-known name not only in sporting circles but also beyond. From the professor, coach, and prominent personality Zyber Konçi, to Doctor Xhavit Konçi, Agim – the dancer of the National Ensemble of Songs and Dances – and Lulzim Konçi, a physical education official and FIFA football referee. Today, nearing his 80s, spending time between Tirana and New York with his daughter, Konçi – as friends and colleagues call him – enjoys a coffee and a cigarette, just like in the old days, without overdoing it. A life divided between football, being an educator in several schools in Tirana, a referee, and later an observer, until he stepped away from active sports. “In Beijing, during the match, I asked our footballers to commit a deliberate foul so I could demonstrate the card, but they argued with me, refused, they were afraid,” Konçi recalls.

Konçi, how did you begin your career as a referee?

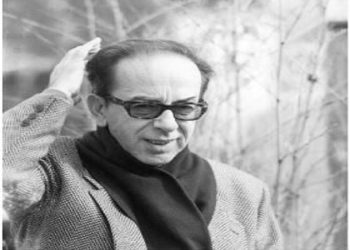

Initially, I was a football player, a midfielder with the youth team of “Tirana” and later with “Dinamo.” Around 1965, I started frequenting the Refereeing Sector, and that’s where my career as a football referee began. From a First Category referee, I became a FIFA referee in the early 1970s until I retired around 1990. I am part of the generation of referees trained by Ramiz Kuka, Sami Kotherja, etc.

You have directed many matches, even as far as China?

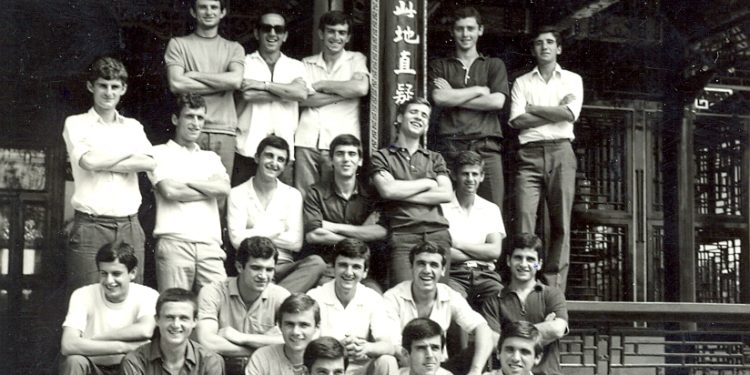

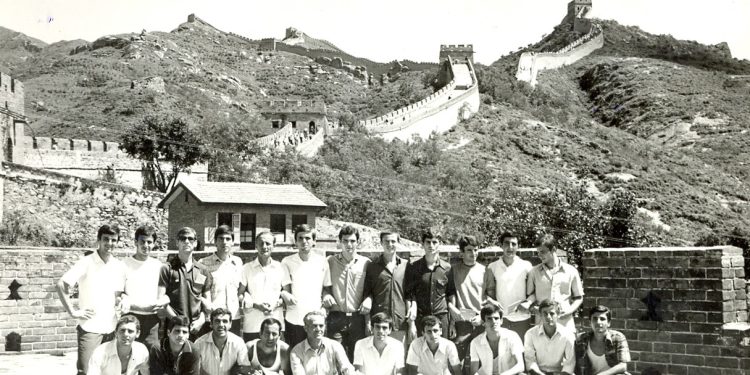

Certainly. Both in national championships and international ones, including club matches and various tournaments, such as the one in Sofia 1979 (World Cup qualifiers for youth) in August 1979. Also in the Far East, as you are recalling, in the summer of 1974.

You set off back then for the People’s Republic of China…

Along with the representative youth team that was leaving for that friendly tournament, the AFA (Albanian Football Association) also appointed me as a referee.

Was there a reward? How were you treated financially?

From the first match I directed, the Chinese liked me, saying, “The level of the Albanian referee is very high and we need to learn from him.” After that, I refereed all the matches with rotating local assistants. Of course, there was a disparity in refereeing levels. There was no financial reward, but they placed a car at my disposal.

How did you communicate with the assistants?

Only with a few words we learned there, like “zoshang ho” (good morning), “ni ho ma” (how are you), “peng” (friend), “tunze” (comrade), “hao i” (good night), “la zhel” (come here). I remember that during match breaks, they brought us orange sodas and other refreshing drinks because the heat was intense.

This was the period following the Nixon-Mao Zedong meeting; what was the political atmosphere?

In the 1970s, relations had begun to change, but during that month, we did not see or observe any moment where complicated or tense situations might arise. Everywhere we went, we were accompanied by a great spirit of “unbreakable friendship,” as it was called in that period.

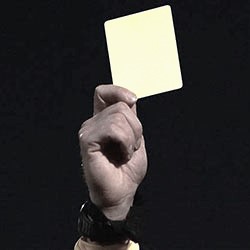

Coming to the card, how did the idea come to you?

By receiving information that in China, cards had not yet found application, due to the fact that China was not a member of FIFA. Chinese football in those years, for political reasons, was detached, isolated from the wider sporting world, without participation in major world events with clubs or national teams.

Had you brought out the card in the earlier matches?

No, because in those matches there was no opportunity to show cards. The matches were held in a high spirit of friendship and understanding. We were instructed to behave correctly, as were the Chinese. However, in a friendly we saw in Tianjin somewhere, between a Chinese military team and a Vietnamese one, it was chaos with no punishment.

And to make it concrete…?

The idea of showing the yellow card began to nag at me, but a moment had to be found and something improvised. I couldn’t do it with the Chinese; I had to provoke it with our footballers so I could demonstrate it publicly.

We are in Beijing and the last match was being played, right?

During the week, with Refik Resmja and Nimet Merhori, we discussed it in the hotel room. I told them that as something new from the World Cup, the yellow card would be good to show here, so the Chinese could become familiar with it. But they did not agree.

“Don’t get us in trouble,” said the Sigurimi (Secret Police) officer who accompanied us. But I had decided, and the night before the match, Refiku told the Sigurimi officer: “He has decided to show the yellow card tomorrow!”

Did you tell the players?

I didn’t tell anyone except the translator, Lin, to whom I explained that if I showed a yellow card, the purpose was to make FIFA’s new rules known in China.

Were there refusals or objections?

The match took place at 10:00 PM because of the high temperatures; that’s why they played the matches late. During the game, I told the players, from Captain Starova to Tit Hyseni (our flag bearer), that as defenders they should commit a foul. But no one dared and no one agreed.

“Why me?” one would say. “No, I won’t foul the Chinese, they will punish us…” said another. They were afraid. During the first 45 minutes, this debate continued. It was truly a hassle, because a heavy tackle could be considered an action that might even damage the friendship…!

And who was the “victim” player?

In the second half, when Dion Kushe, an honest player, intervened against an attacker, I blew the whistle loudly and long, and the play stopped. Without hesitating, while running, I pulled the yellow card – which FIFA had given me – out of my right trouser pocket and, with my hand stretched high, in a very visible manner, I pointed it at Kushe. He was surprised but said nothing, as the matches were disciplined. He even went to the player lying on the ground, embracing him and apologizing.

So you are the first referee of a card?

I remember that the 100,000 spectators broke into applause because they had never seen such an action. Meanwhile, the public address system began explaining in their language: “The Albanian referee, Konçi, has shown the yellow card, which FIFA began applying after the World Cup in Mexico. This card is given as a warning to footballers who violate the rules.”

Were you emotional?

Naturally, and greeting them, I turned to the stands, thanking them and bowing with my right hand over my heart. The game was interrupted for a few minutes and restarted after the medical staff, which came to assist the injured player, left the field. That was the first and last card. If I hadn’t shown it there, I wouldn’t have had another chance.

How did the game end?

As I said, this was the last of the 9 tournament matches and took place at the “Workers’ Stadium” in Beijing. We were facing their national youth team, like ours, and it ended 2-1 for our team, with two goals if I’m not mistaken, by Metani. Although results, as was known, were determined by “friendship,” we won several of them.

What is the story with the Mexican dancers in China?

We were in Beijing, when at our hotel – the best at the time, with 12 floors – the translators and companions stayed on the third, while we were on the 10th. An artistic group arrives there, with beautiful Mexican girls. The ensemble was called “Juvenilja.”

They spoke Italian, and our boys fell in love with them. One night they had arranged to meet, and while they were descending the emergency stairs, they were discovered.

What happened next?

The Sigurimi officer had heard a noise and, going out, had seen them leaving secretly with them. He informed us, we went out, but they ran away. The staff gathered and held a meeting at 2:00 AM in the hotel.

Exactly at that time, an Albanian student had fallen in love with a foreigner, and as punishment, they had isolated her in the embassy; her return to Albania was by ship, a 6-month journey.

For our players, they had a harsh discussion. “These people belong in prison!” shouted the Sigurimi officer. “No,” Resmja countered, “they are the children of our comrades.” “If you speak to those dancers even once more, we will send you back to Tirana,” they were ordered, and the matter was closed.

What else do you remember from that tour?

The journey – departing from Tirana to Iran, then to Beijing. The planes had no air conditioning; on the long road, air would leak in. “The plane is burning!” someone shouted out of fear. There we spoke a little Italian and some Chinese words. I remember Ilir Bushati when he dribbled past opponents and Resmja getting angry with him.

Or when they sent us to watch opera performances. Then the tea cups, the gift sets that you couldn’t come back from China without. The return, then from Beijing to Moscow and Budapest, where we stayed for two days.

Tell me a bit about Loro Boriçi…?

In China at that time was Doctor Profit Cani. We found him there, along with Loro Boriçi, who waited for us for hours at the airport. Very humble; the Chinese spoke the best words about him. But “the one with number 10” – that’s what they said about Resmja, as Refiku was the most popular Albanian player the Chinese knew, having been there several times.

But the saleswomen in a supermarket, when they recognized Gezdari as an actor in an Albanian film, called the translator to make sure and asked him.

After all these years, together with the card….?

That was an unforgettable month, a wonderful group, players, coaches, without forgetting the translator Lin, with whom Resmja joked about the Albanian language. The card had an echo even in Albania.

When we returned, driven by curiosity, that action was recounted with humor in sporting environments or friendship groups – even on the train when we traveled, they would ask me: “Konçi, tell us how you pulled out the yellow card that amazed the Chinese…!”/ Memorie.al