Part Nine

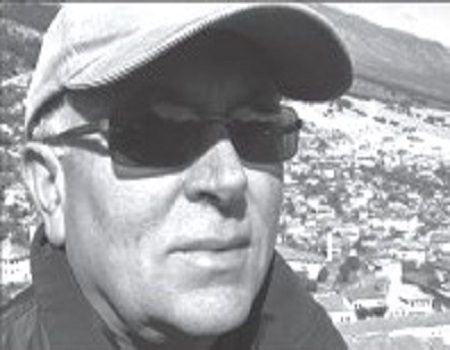

Excerpt from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, a Noble Bookstore and Newspaper’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / When we, Alizot’s children, would recount “Zotia’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No! What a shame, they will be lost…! Who should do it?” And we felt increasingly guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones to do it. But could we write them?! “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zotia used to say whenever he came across poorly written books. As we, Zotia’s children, discussed this “obligation” – the Book – among ourselves, we naturally felt inadequate to the task. It was not a job for us! By Zotia’s “yardstick,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the previous issue

– IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT EMIRI –

BY THANAS DINO

WHEN WE GATHERED AT ZOTIA’S

I would find it unbelievable even to myself if, in the books of the “Southern Library” series, I had not mentioned – even in passing – the name of Alizot Emiri that distinguished bookseller of Gjirokastra, who, I believe, leads the ranks of its proverbial figures.

A short speech of mine for the 70th anniversary of Pano Çuka’s birth, on May 6, 1995, was titled: “When we gathered at Zotia’s.” (“Report from the South”).

Much time has passed, people and regimes have gone, but one thing hasn’t changed on the first cobblestones of the Middle Bazaar in Gjirokastra: the name; “te Zotia” (at Zotia’s), the shop that cannot be imagined as anything other than a bookstore.

Thanks to Zotia, that bookstore functioned as an intellectual headquarters. When we first discovered it, we were young and green, and we didn’t have the status to enter – in the sense of staying or lingering there. Dr. Vasili i Madh, Lefter Dilua, Pano Çuka, Bekim Harxhi, Agim Shehu, Spiro Kufoi, and others from Gjirokastra gathered there, along with all the men of the pen and arts coming from Tirana. We would watch from behind the glass panes.

I don’t believe it was just the newspapers and books that brought them together; it was more the shop owner himself. Alizoti and Dr. Vasili i Madh, who even had the same haircut, looked like Germans to us; Iljaz Babametua looked Italian; Lefter Dilua was known as the man of French culture; Pano Çuka and Spiro Kufoi looked Greek.

Gjirokastrians, as a type, are not expressive; they are careful, calculating people who don’t speak much, and it would be a matter of great curiosity to know what texts and subtexts their conversations about the times held in that bookstore.

Like others, Zotia walked with a measured but steady pace (serbes), unconcerned with the times or the politics of the day, like people who are used to living and making history; history passed through the middle of the Bazaar, the men of the Bazaar were there and didn’t care much for it; built this way, they must have had a disdain for the mundane; “the things we have seen,” in a word.

Zotia used to say: “From my readings of French and Russian literature, even if you dropped me in the middle of Paris or Moscow, I would know where to go, how to orient myself.” I think he lived through the book. Some said Zotia would only glance at the prefaces and, by natural gift, was able to sustain discussions about the books, but I judge that he knew what and how to read. He knew all the Albanian writers and would tease them with his humor and wit.

It is worth telling how that “heavy” headquarters opened for us, my generation. It is well known that at that time, the only entertainment and relaxation was reading. We searched for books with great zeal, and the wonder was that for some – who perhaps had caught his eye for their passion for reading – Zotia did something incomprehensible, even forbidden: he would give us the new book as if it were a library, advising us to keep it well, read it, and return it. We were amazed and thanked him; I am still amazed today when I remember that noble act, unheard of elsewhere.

With his humor and witty remarks, he kept the Bazaar alive; they were carried far and wide, just as they still echo today. Gjirokastrian humor is not the kind that just makes you laugh; it is mostly irony, deep subtext, clever counterpoint, and ambiguity. But I do not wish to artificially comment on things I am not certain about. The episodes with the shops across the street, involving a barber named Kekezi, are particularly remembered! “May you never fall under his humor,” might have been a wish that friends and colleagues made to one another. And they were right.

My mother and his wife worked together at the Military Tailoring, as it was called. It happened that we were together as families at parties or collective celebrations. He would start his humor by teasing his wife – she was wise too, but she didn’t talk back, nor did she take his remarks the wrong way in front of others. Even such simple events opened before me what I later called: “The World of Gjirokastra.” Zotia was from the center of that world.

It isn’t clear to me why, under that regime, Zotia’s family had a political “shadow.” Once we mentioned it with Elmaz Puto – I don’t remember well if he was the Chairman of the Executive Committee or the First Secretary at the time – a man who helped him by protecting him politically. “They say that about him, but they’ve forgotten he also has this,” was his logic, but the facts and arguments he brought are not clear to me, not even vaguely.

Though not from a very large clan, the Emiris and Zotia belonged to those Gjirokastrians who could not easily boast, but were even harder to strike or trample upon. The age difference didn’t allow me to discuss such matters with him, but I have the impression that he didn’t even show them and, deep down, he didn’t care much about them. He was one of those who had seen much and knew the transience of history.

One December, when I was to write the New Year’s reportage with the joyful things of that time, I had chosen the construction of a tourist venue called “Kupola,” across from Përmet, on this side of the Vjosa, inside the greenery, which retirees called the “pressure cooker” because of its cylindrical shape. The project was designed by Zotia’s eldest son – Ibrahimi, an architect and designer who had worked in Përmet for many years.

“Don’t mention him,” some veterans I associated with told me, a matter about which he would occasionally mock me: “Where would they let you stay with us. Ibrahimi has something in his biography,” they would say. “You’re telling me about that family?!” I told them. “To me, who comes from Gjirokastra, you’re going to tell me their biography?!” I didn’t listen to them, of course; I mentioned the author’s name, because the work was beautiful – not just for that time, but even for today.

The last time I saw him, as I remember Alizot Emiri: I was leaving the Executive Committee where I worked, I believe at the end of official hours. Alone. He, also alone, was climbing the cobblestones that lead to the middle of the Bazaar, with his hands behind his back. I greeted him and then asked: “Are you out to do some shopping (pazar)?”

“Listen,” he told me, “I never do the shopping, so that when I die, they mourn me, and not the grocery bag.”

It was a time of great market shortages, of lines, of long waits, and many families burdened retirees with this task. But Zotia was one of those who were not easily subdued or put in a line.

It has been said by some in Gjirokastra, even in whispers, that a bookstore named “Alizot Emiri” could be opened. It seems to me a proposal that stands; it would be a very beautiful thing. / Memorie.al

Gjirokastra, November 21-23, 2010

To be continued in the next issue