Part Eight

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, the Library, and the Noble Soul’

TWO WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / When we, the children of Alizot, used to tell the “stories” of Zotia (Alizot) in joyful social settings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No! What a pity, they will be lost…! Who should do it?” And we felt increasingly guilty. If it had to be done, we should have been the ones to do it. But could we write them?! “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zotia used to say whenever he handled mediocre books. When we, Zotia’s children, were discussing this “obligation” – for the Book – we naturally felt our inability to fulfill it. It was not a job for us! By Zotia’s “measuring stick,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the previous issue

IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT EMIRI

By Dr. ADEM HARXHI

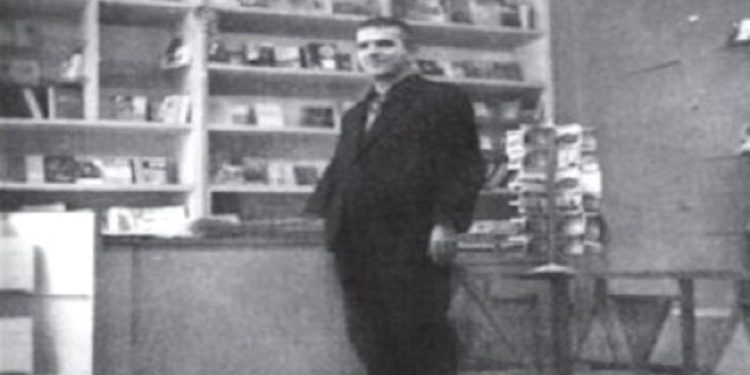

THE LEGENDARY BOOKSELLER

Every time I left my house, like many other Gjirokastrians, I would head to Alizot’s shop. We went there to buy a new book, but also to exchange or listen to a wise word. He didn’t just sell books. He was an excellent literary analyst and lecturer. He analyzed books with intellectuals as if it were a literature class. This amazed me, and I am convinced that this was not advertising; it was passion, which is why he did it for many years and in an exquisite manner.

“I’ll wait for you at Alizot’s,” I told Rustem on the day he was summoned to the District Party Bureau after having “insulted” one of the Party Secretaries.

The First Secretary of Gjirokastra at that time was Piro Gusho. As soon as he arrived in Gjirokastra, the first thing he did was imprison several hospital doctors. He did this everywhere he went.

“Like the groom who killed the cat on the first night of the wedding to terrify the bride,” Alizot once said.

Rustem arrived and began to tell what had happened at the Bureau meeting.

“They criticized me severely,” Rustem said. “The First Secretary told me: ‘You dared to insult Comrade Kristo. Do you know that Comrade Kristo is a member of the Central Committee of the Labor Party of Albania?!'”

At this moment, Alizot interrupted:

“What, is the Central Committee a pancake (kulaç), that each of them has their own piece?”

We smiled and left. This was Alizot’s subtle humor.

These were the years when friendship with China was flourishing. A prominent Chinese professor, a specialist in “Convention Diseases,” came to visit Gjirokastra. The professor had recently returned to China after studying and working for many years in America.

In the Castle, while admiring the city from the highest vantage point, the professor asked me:

“Is there a restroom here?”

“No,” I said, “just let it go somewhere here.”

He went behind a ruined wall.

After the visit, we went down to the “Hotel Turizmi.” He liked the city very much, with its characteristic buildings and cobblestones like a carpet. We returned to Alizot’s shop, whom we found sitting behind the counter, with a thick hand-rolled cigarette at the corner of his lip.

He stood up, as he did whenever people entered the shop.

I explained who the guest was.

“Did he like Gjirokastra and the Castle?” Alizot asked.

“Very much,” the guest replied. “I had never seen a city like this. But, I regret that I had to leave an unpleasant memory there.”

Alizot looked at me, surprised. The professor, noticing Alizot’s curiosity, said:

“I urinated behind a wall… I had no choice. There were no bathrooms there.”

There were notes of humor in his words.

“You did well,” Alizot said. “You couldn’t become a Kuznetsov.” The professor laughed at this humorous intervention.

Dr. Cetbauer, a professor of ophthalmology from Vienna, also visited Gjirokastra. When we entered the bookstore, the Professor approached the counter to look at the books. Alizot assisted him. He picked up Enver Hoxha’s book, “Reflections on China.” After flipping through a few pages, the Professor said:

“This is your third divorce. Now you are like that good man who has separated from three wives. Who would dare give him another wife?!”

Alizot and I looked at each other, and he replied jokingly:

“It doesn’t matter how many times we divorce, we won’t be left without a bride. We are of noble stock (sojli)…!”

I doubted if the professor fully understood the Gjirokastrian word “sojli,” but the Austrian nodded, smiled, and we left.

When I was working in Budapest, I met Dr. Cetbauer at his clinic in Vienna.

As soon as he saw me, he asked:

“Have you found a bride, you noble ones (sojlinjtë)?”

“No, not yet,” I told him.

He remembered the conversation at Alizot’s.

It was the beginning of the 80s. An English journalist working for the World Health Organization came to visit Gjirokastra. He had just written a valuable book on global health problems. He donated a copy of the book to the hospital.

We entered Alizot’s shop. The friend looked at the stands and flipped through the books on the counter. At one point, he turned to Alizot:

“Do you see that gate over there?” – pointing from the window to the shop across the street. – “Why is that small hole needed in the bottom corner of the gate?”

Alizot came out from behind the counter and said:

“Are you talking about this hole?” – showing the guest a similar one in the gate of his own shop.

“Yes,” the guest said.

“We have it for the cat, so it can enter and hunt mice. We have these in the internal gates of our houses too.”

“I have traveled to many places in the world because of my work, but I have never seen this practice anywhere,” said the guest.

“Spread it as an Albanian experience for the eradication of mice. We distribute experiences!” Alizot said mockingly.

A few months later, I received a letter from London. It was a newspaper page with photographs of an alley from the Gjirokastra bazaar. There, the gates with the hole at their bottom were visible.

I brought only a few moments of Alizot’s clever humor. Such moments happened every day. Alizot was and remains a character and a personality of the city. Anyone even today says: “at Alizot’s,” “opposite Zotia,” “above and below Alizot,” just as they say in Gjirokastra; at “Premto’s bakery,” at “the seven springs of Meçite,” “at the Power Plant,” and others. Alizot has become a cultural milestone for Gjirokastra. Everyone knew him, fellow citizens and those who came as visitors or on official business to Gjirokastra.

Friends, even if they came for a few days, would spend some moments with Alizot, with his humor and his books. Those who entered that shop, as Lela told me while I was writing these lines, would come out smiling from the humor and conversations with Alizot. For everyone, he was an open book of culture and the ancient wisdom of the aristocratic city.

Whoever was born, raised, and worked in Gjirokastra, as I was fortunate enough to do, had finished a university before even going to school – the University of Gjirokastrian Civic Education. The teachers of that University were Alizot and his friends, our parents, to whom I bow with respect.

Every year I have gone to Gjirokastra, the last time was in the summer of 2009. It was a warm afternoon when, with Lela, I went out to reconnect with the city of my dreams. Every time I go, I feel saddened. The Bazaar is not what I had left in 1985. It has lost its beauty and grace.

On the shop ledges, in small groups, Gjirokastrian men and boys sat and talked. When I approached them, they would stand up and we would embrace. It was the mutual gratitude of people from a city full of “shilë e nostimadh” (wit and charm).

They all asked me the same question:

“Do you recognize me?”

They were all younger than me, but I recognized many of them. Even if I didn’t recognize them, they resembled their fathers, their kin, people with whom I worked for years and who, with their civility and kindness, made me serve them as their own son and did not allow me to fail.

I also saw Zotia’s shop. It was no longer a bookstore. Now, fruits and vegetables were sold there. The Bazaar had changed. Several small businesses had opened, but the beloved bookstore was missing. The knowledgeable, wise, and humorous bookseller, the sage Alizot Emiri, was missing.

Would it not be better if that shop were a bookstore bearing his name? Let that valuable and beautiful tradition continue.

One summer, recently, I learned that the “Kadare” bookstore had opened in Tirana.

I was very happy and went to visit it. It was truly a good bookstore. There were places where you could read comfortably and where you could also have a cup of coffee. It was organized like “Barnes & Noble” or “Borders” bookstores in America, naturally on a smaller scale. Ismail is my childhood friend and a world-renowned Gjirokastrian writer. In honor of his work, I had to go to that bookstore. I remember it was a hot summer day.

I bought thirty pocket-sized books, editions of ABC KLASIKËT, recommended by my friend, Spiro Dede. I sat down to leaf through them and drank a bitter espresso. I was pleased by those editions and the coffee. I went to that bookstore several times. I returned to America with the books and very good impressions.

The next summer I was in Tirana again. I headed for the “Kadare” bookstore. What did I see! It was no longer a bookstore. A large “fast-food” advertisement awaited me there.

Dejected, I returned home. A question hung in my mind: “Why had they destroyed that comfortable and beautiful bookstore?!” I felt sorry.

Ismail, the distinguished writer, Honor of the Nation and the city, and the legendary bookseller Alizot, do not have their names where they deserved to be more than anywhere else. These two places, which should have distributed culture, were replaced by food shops. Something is not working with us, I thought, which is why we struggle and cannot find the road to progress…!/Memorie.al

New York, March 1, 2011

To be continued in the next issue