ALBANIA: BETWEEN NATIONALISM AND SOCIALISM

Memorie.al / Irritated that Albania “premeditatedly continues to aggravate relations with the Soviet Union,” Russia, last week, ordered its ambassador in Tirana to pack his bags and head home. On the other hand, Albania’s ambassador was also ordered to leave Moscow, as both countries exchanged mutual accusations of spying and bugging their respective embassies. It was the first time that two “Red” nations had severed diplomatic relations (not even in 1948, during Stalin’s spectacular break with Marshal Tito’s Yugoslavia, were diplomatic ties cut). Since the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, where Khrushchev publicly denounced Albania for its defiance of anti-Stalinist directives, the tiny country has become a “surrogate” where Moscow and Beijing squeeze their conflicts.

By officially breaking with Albania, Khrushchev is now trying to reconcile with Beijing, without forcing Red China to either draw closer or deepen the existing rift. Meanwhile, Albania continues to loudly defy Moscow as the last enclave of Stalinist-style communism in Europe.

Portraits and Police in a “Balkan Shack”

Elsewhere in communist Europe, once-ubiquitous busts and portraits have disappeared, but visitors who have recently set foot in Albania – notably a group of German journalists – still find Stalin’s old portraits and methods in this forgotten Balkan shack. In the capital, Tirana, in the broad Skanderbeg Square, three traffic policemen are seen on duty in white uniforms, but there is no traffic for them to direct.

Heavily armed soldiers and police stand before ministries and embassies, on street corners, in parks, and in front of and behind hotels. Other guards carry submachine guns and pace before the residences of top Red officials to protect them from “overly enthusiastic admirers.”

Beyond those in uniform, Tirana is flooded with men in civilian suits from the Sigurimi, Albania’s secret police. Their interrogation methods range from the use of poisonous snakes to electric shocks that violently shake a prisoner when they try to stand or sit. According to a UN report, 80,000 out of Albania’s 1,700,000 inhabitants were deported to concentration camps between 1945 and 1956, and 16,000 of them died there.

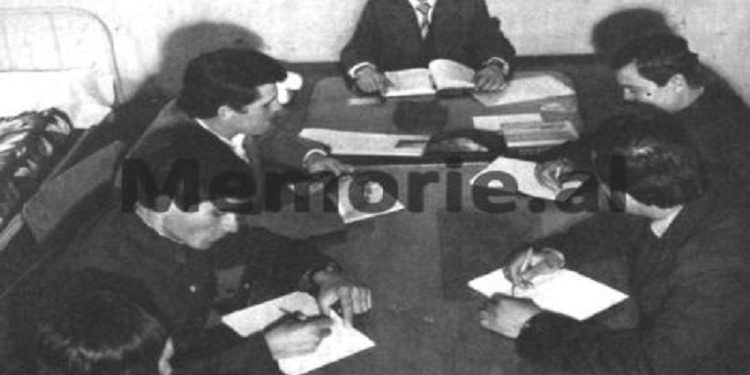

Trials and “Shadows”

Last autumn, a group of dozens of Albanian Naval officers appeared before a makeshift trial at the “Partizani” cinema, accused of being pro-Soviet spies. They were found guilty and immediately taken to a nearby abandoned site and executed by a firing squad.

To a casual tourist, the Sigurimi seems more comic than lethal. Entire squads of two shadow foreign visitors. Any attempt to speak with an ordinary Albanian fails, as the latter lose their voices after receiving a warning nudge on the shoulder from plainclothes agents. One tourist at Durrës beach managed to evade them by swimming far out to meet an Albanian girl in a bikini. Wading in the water, she said: “I would like to talk to you at length, but you must know that in this country, it is impossible.”

The Orator and His “Clan”

Visitors rarely notice any tendency among Albanians to criticize the government or denounce the country’s backwardness, and the Sigurimi is not the only reason. Traditionally proud, suspicious of foreigners, and steeped in a clan mentality, Albanians stubbornly refuse to complain about their country to outsiders. Most would simply stutter and lower their heads, saying: “You must understand us!”

The same national mentality is manifested in the Red leader, Enver Hoxha. Albanians have a Mediterranean penchant for fiery, denouncing speeches, and Hoxha is well-known, even among his enemies, as a master of this oratory. Tall, handsome, with sleek hair now turning gray, Hoxha reaps loud applause for his insults toward Khrushchev.

Hoxha’s portrait hangs on almost every wall. His profile appears on the national currency, the Lek, and at meetings of the Central Committee (where most members are related to each other and to the leader by blood or marriage). Hoxha speaks from a podium adorned with a plaster bust of him.

A Spoiled Bourgeois Turned Dictator

Like his country, Enver Hoxha is full of surprises. Instead of a rugged highlander chief, he is actually a former schoolteacher and the spoiled son of a wealthy Muslim merchant. Despite his “tough guy” (garip) mentality, his manners are those of an educated bourgeois, reflecting his schooling in the universities of France and Belgium.

During WWII, Hoxha united the leadership of communist guerrilla groups and not only liberated Albania from Italian occupiers but also eliminated rival guerrilla groups and dissenting voices within his own party. Consequently, today, of the 14 original members of the Politburo, Hoxha is the sole survivor.

Contrast: Donkeys and Mercedes

His closed Stalinist regime has done little to lift the weak Albanian economy. The few paved roads and large buildings are relics of the Italian occupation. There are no private cars or buses; Albanians travel from village to village by donkey or in open trucks. The only railroad is just 70 miles long, and the only seaport, Durrës, can process only one ship per day.

The greatest contrast is between the poverty of the masses and the grotesque luxury of the communist elite. There is no middle class between the peasant with a donkey cart and the official driving a “Mercedes” from the state garage. Tirana has a TV station that broadcasts to a total of 200 television sets in the country, all owned by party officials. While workers patch their pants with rubberized rags, the new “jet class” wears Italian-cut suits and impressive evening gowns.

The Chinese Influence

Soviet technicians have been replaced by Chinese ones. The Chinese receive the same wages as their Albanian colleagues and spend their free time devotedly studying the difficult local language. However, most xenophobic Albanians view them as if they have just emerged from a zoo. Chinese films are shown in countless open-air cinemas, where students often hiss at the blind official propaganda in the dark.

Albania has historically faced powerful neighbors, from Rome to the Byzantine Empire to the Turks. Even under communism, it seems it hasn’t lost its talent for having a complex about being ignored. Whether Enver Hoxha continues this way depends not on him, but on distant Red China. For now, Hoxha continues to denounce Khrushchev as a traitor to Marxism, while the “Peking Review” proclaims that: “Albania will always stand like a granite rock, remaining the only fortress of the socialist camp in Southeast Europe.”/Memorie.al

Friday, December 22, 1961