By Prof. Dr. Aleksandër Meksi

First part

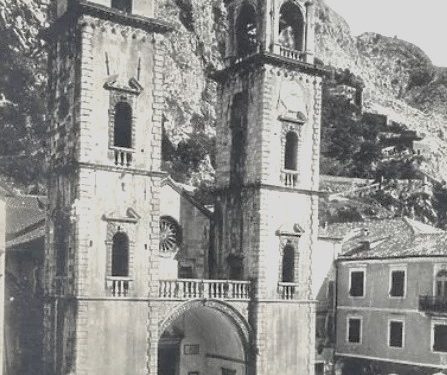

Memorie.al / Mirdita, with the Holy Mountain above Orosh, has been over the centuries the center of great veneration by the Christian population, not only of the region but also beyond, reflecting the significance and renown of the local abbey and its historical role. Indirect evidence of this lies in the vast number of legends and stories associated with it; the saint and the region. The first mention of a Diocese of Arbanon, “Lazarus episcopus Albanensis,” is found in the consecration act of the Church of Saint Tryphon in Kotor in 1166, where, alongside Lazarus – who consecrated the altar to the left of the main one –“Andreas prior Albanensis” also participated.

This diocese and the Principality of Arbanon, as suggested by Andreas’s name and title, are objects of extensive scientific research aiming to shed light on various aspects of their history, often with varying results. To judge this diocese accurately, we must follow its progression over time, determine its geographical extent, and clarify several historical issues. In the mid-12th century, regarding church organization, the territories inhabited by Albanians fell under the jurisdiction of several ecclesiastical centers.

In Northern Albania, under the Catholic Archdiocese of Ragusa-Epidaurus, the following dioceses were dependent: Bar (Auarorum), Ulcinj (Licinatensem), Shas (Suacinensem), Shkodër (Scodrinensem), Drisht (Driuastensem), and Pult (Polatensem). In Central Albania, we have the Metropolis of Dyrrhachium (Durrës) with the dioceses of Lezha (Elison), Stefaniaka (Stefaniakon), Kruja (Kroon), and Kunavia (Hunavian). In Eastern and Southern Albania, the Archdiocese of Ohrid with the dioceses of Gllavnica, Deaboli, Kanina, and Dibra. In Southern Albania, the dioceses of Himara, Butrint (Buthrotit), and Drinopolis (Drinopoleos) fell under the dependency of the Metropolis of Naupactus.

Among these, the dioceses of Northern Albania belonged to the Catholic Church, otherwise known as the Latin Church, to which the Catholics or Latins (lëti) of Dyrrhachium were also linked, led by an archdeacon – evidence of a coexistence with the Orthodox. The path of formation for these structures and their leanings toward the East or the West resulted from specific historical and cultural conditions these lands experienced during previous centuries.

Historical study of administrative and ecclesiastical organization has shown that during the 8th and 9th centuries, the church in territories inhabited by Albanians did not practically depend on the Patriarchate of Constantinople. We believe this is explained, on one hand, by the difficulties of connecting Dyrrhachium to the imperial capital and, more importantly, by its stronger ecclesiastical ties with Rome and the Latin Church. The inclusion of Dyrrhachium under the Patriarchate seemingly occurred around the end of the 9th century (Synod of Photius in 879) and was sanctioned in the early years of the 10th century.

This is evidenced by a notitia from the time of Leo VI, dated around 901 – 907. In this notitia, Dyrrhachium – the 42nd Metropolis in rank – oversaw the dioceses of Lezha, Kruja, Stefaniaka, and Kunavia; essentially the lands between the Drin River to the North and East, and the Shkumbin to the South, which at this time were almost entirely the lands under the Byzantine Theme of Dyrrhachium. Further south, up to the Vjosa, were the lands occupied by the Bulgarians around the 860s, and further below, the Theme of Naupactus.

While for the 10th century we know the ecclesiastical organization of the Metropolises of Dyrrhachium and Naupactus and their suffragans, historical documentation lacks data on the dioceses depending on the Bulgarian church, as well as on the northern territories of the Theme of Dyrrhachium, whose extent up to Antivari we know from “De Administrando Imperii” by Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

Of great interest is also the so-called notitia of John Tzimiskes (969–976), which should be linked to the restoration of Byzantine power after the collapse of the Bulgarian kingdom – namely in the last quarter of the 10th century. According to it, the Metropolis of Dyrrhachium extended to Antivari and the interior of the Vlora bay, overseeing 15 suffragan dioceses, including: Antivaros, Likinidon, Skodra, Drivasti, Dioklea, Polathon, Elison, Kroon, Stefaniaka, Hunavia, and Cerëniku.

However, this state of affairs did not last long, because in 1022, the dioceses of Bar and Ulcinj were severed from Durrës and linked to the Roman Catholic Church through the Archdiocese of Ragusa-Epidaurus. This came as a result of previous ties to the Latin Church and Rome’s efforts to assert itself as a universal power. From this time, a new phase of connection with the Catholic Church begins.

Thus, in 1089, the anti-pope Clement III, upon the petition of King Bodin of Dioclea, transferred the dioceses of Northern Albania to the Archdiocese of Dioclea-Antivari. These were the dioceses of Bar, Ulcinj, Shkodër, Drisht, and Pult. From this, it is understood that they continued to be dioceses since the end of the 10th century (perhaps in some cases with interruptions), while the Diocese of Shas was a new creation.

With the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Latins in 1204, favorable conditions were created for the advancement of the Catholic Church in Albanian territories. Naturally, this was not achieved easily due to the resistance of the Orthodox Clergy, both in Dyrrhachium and in the dioceses in the interior of the country. Since the 11th century, the presence of an Amalfitan colony and slightly later a Venetian one is evidenced in Dyrrhachium, each having its own churches.

For the Amalfitans, a church is evidenced in historical documentation in the mid-14th century, but it is understood they must have had this church since the time they were the sole Western colony. For the Venetians, we have the evidence of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos granting them the Church of Saint Andreas near the port in 1082. Besides these, the connections of Catholic believers with organized structures like the archdeaconry are evidenced as early as 1200.

We believe that the limitations imposed by the Byzantine Emperor Basil II on the Metropolitan of Dyrrhachium through his diplomas of 1019 and 1020 were also due to the tolerant stance toward the Latin Church by the Orthodox of Dyrrhachium. An organized Latin church with chapels and properties is evidenced by traces of Pre-Romanesque and Romanesque-Gothic sculpture in Durrës, as well as the ruins of the Church of Saint Mary of Brar east of Tirana, where we have the tombstone inscription of sevastos Mihal Sgura (year 1201) in Greek and Latin, along with fragments of mural painting with Latin signatures.

With the conquest of Durrës and part of coastal Albania by Charles I of Anjou and the formation of the “Kingdom of Albania,” changes occurred in the ecclesiastical status as a result of the Catholic Church’s efforts. We have what Šufflay calls the third phase of Albania’s ecclesiastical organization. From this time, through the intervention of Bar and Dyrrhachium and the establishment of Dominican and Franciscan orders in Albania, a period begins characterized by an “offensive” of Catholicism against Orthodoxy, particularly in Central Albania down to Vlora.

These efforts yielded results with the creation of several new Catholic dioceses, such as Sapa (behind Orthodox Lezha) in 1291, Balec (before 1347), Danja (before 1361), and Vrego (on the banks of the Shkumbin) before 1353. During Angevin rule, Catholic dioceses were also established for Vlora in 1273 and Kruja in 1279, which functioned as long as those centers were under the Angevins, with their titulars later staying elsewhere.

Later, the Catholic Church assimilated the dioceses of Kunavia (Canoviense) in 1310, Stefaniaka (Stefphaniense) in 1363, and Lezha (Alexiense) in 1357, while the Orthodox Metropolis of Dyrrhachium is mentioned for the last time in 1343, after which it faded and its formal titulars resided elsewhere depending on political circumstances.

However, during the period under review, a distinction must be made between the faith of the feudal lord and the episcopal see versus the faith of the local clergy and the masses. On this, some reports from the late 13th and early 14th centuries shed light. Thus, in 1265, Pope Clement IV, writing to the archdeacon of the Latins of Durrës, confirms the specific character of Albanian Latinity.

Later, in 1295, a treatise by the Genoese Galvano di Levante states that feudal lords of the Sguraj, Blinishti, Mataranga, and Thopia families are “neophytes” in terms of faith. Therefore, conversions to Catholicism were never final, and the Angevin archives in Naples speak clearly of this.

Moreover, it is difficult to determine the faith of the population in the interior of the country, as changes in clergy leaders often did not affect lower ranks. In an anonymous description from 1308, it is stated that in the dioceses of Central Albania (Kunavia and Stefaniaka) and the northern ones (Pult and Dibra), the inhabitants are neither Catholic nor Orthodox.

Ultimately, we would say that by the mid-14th century, the Catholic Church, after decades of offensives against Orthodoxy, had managed to expand – besides Northern Albania – into Central Albania, bordering the territories that ecclesiastically depended on the Archdiocese of Ohrid. Entering under Venetian rule at the end of the 14th century for coastal cities, and under Turkish conquest for the rest of the country starting from the second decade of the 15th century, made this state of affairs almost final.

Preserved documentation shows that under the Archdiocese of Antivari were the dioceses of Ulcinj, Shas, Shkodër, Sapa, Danja, Balec, Drisht, Pult, Prizren, and Arbanense; while under Durrës were Lezha, Stefaniaka (with Benda), Kruja, Kunavia, Vrego, and Vlora, although some of them existed only briefly. Let us now address, based on historical documentation and studies, the history and territories administered by the Diocese of Arbanon, as well as the principality of the same name.

As mentioned, we have the first evidence of it in June 1166, where Lazarus “Episcopis Albanensis” or “Arbanensis” participated in the consecration of the altar of the Church of St. Tryphon in Kotor. A year later (Dec. 20, 1167), Pope Alexander III addressed this Bishop as “Lazarum episcopum de Albania,” praising him for wishing to deny the Greek rite and for his will to avoid it in many instances whenever the opportunity arose.

On the same day, the Pope, in another letter of official testimony, confirmed the suffragans to the Archdiocese of Ragusa, among which the Diocese of Arbanon is absent – it is also not recognized in many other previous papal bulls confirming Ragusa’s suffragans. Likewise, as seen above, a Diocese of Arbanon is not among the suffragans of the Metropolis of Dyrrhachium or the Archdiocese of Ohrid.

In such circumstances, we believe we are dealing with a diocese created not long before in a territory of the Metropolis of Durrës – thus under Byzantine rule – which, to affirm its existence or due to religious conviction, linked itself to the Archdiocese of Antivari. If the diocese had been established for a long time, it would have been included in the lists of suffragans, especially if it had been severed from any Catholic diocese dependent on Bar.

That the Diocese of Arbanon (Arbanense) was created in territories hitherto belonging to Dyrrhachium is confirmed by the content of the aforementioned letter from Pope Alexander III, in which its adherence to the Orthodox rite (“Greek” in the letter) and its dependency on the Metropolitan – to whom he must show due respect – is quite clear. This is explained by the good relations at that time between the Pope and Emperor Manuel Komnenos. We understand Bishop Lazarus’s participation in the 1166 ceremony in Kotor as evidence of the desire for a connection with the Catholic Church through Bar. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue