Memorie.al / He rest lonely, and perhaps forgotten, there in the Erseka cemetery, beneath the whistling winds of the Kolonja plateau and Mount Gramoz. He awaits an unspoken word for the renowned “Old Man” of Southeastern Albania, who, during the difficult years of World War I, brought foreign generals and diplomats to their knees. But that word was never spoken – neither in life nor in death – by any of the governments that followed: from Zog’s regime, naturally, he expected nothing, as he had turned his rifle against him; from the communists, he received only a few hollow titles of no use to anyone; and from the democrats, total oblivion.

On this anniversary of the start of World War I, in which Albania was one of the greatest victims, it is an honor to mention one of the Albanian heroes of this war: Sali Butka.

Who was Sali Butka?

Sali Butka was born in the village of Butkë, Kolonja, in 1857, into a large family with early origins from Frashër, Përmet. Known by the surname Aliçkaj, they had migrated around 1630 to settle in Butkë. A large but simple family, they began to gain fame throughout the regions of Kolonja, Përmet, Korçë, and Skrapar when Tahir’s son, Sali, joined the guerrilla bands (çeta) formed at the beginning of the 20th century against the Ottoman Empire.

In the First Bands for Freedom

He was a member of the Monastir Committee “For the Freedom of Albania.” In December 1905, Bajo Topulli personally went to Sali Butka’s house, where the first national guerrilla band was formed, declaring the start of the armed uprising. Led by Sali Butka, this group included patriots such as Qani Starja, Qamil Panariti, Riza Veleishti, and others.

In 1907, Butka’s band, alongside those of Çerçiz Topulli and Mihal Grameno, organized the assassination of the Greek Despot, Photios, considered a major enemy of Albania. Following this, the Turkish government imprisoned Sali and burned his homes in Butkë. Later, the High Porte incited their local tool, Dajlan Bej Qafzezi, to murder Sali’s brother, Selman Butka.

In Vlora, Defending the Flag

Recognizing his immense contribution, Prime Minister Ismail Qemali summoned Sali Butka to Vlora and received him warmly. There, he met Isa Boletini, Luigj Gurakuqi, and Bajram Curri. He organized the defense of the new state against Greek military incursions. At the time, the newspaper “Liri e Shqipërisë” wrote: “Sali Butka has unsheathed his sword and is fighting the Greeks… showing bravery as in the time of Skanderbeg.”

With Rifle and Pen for the Motherland

From a young age, Sali read and distributed the works of the National Renaissance, bringing them from Monastir and Sofia. He collaborated with Petro Nini Luarasi, helping him establish the first Albanian school in Kolonja. Alongside Nasuf Bej Novosela, Sali protected Petro Nini from enemies who constantly threatened his life. It was during this time that he began writing patriotic poems, which transformed into folk songs still sung today.

The Two Great Wounds of 1914

The year 1914 brought two heavy tragedies to the “Old Man.” During the battle of Qafa e Martës against Greek forces, his close comrade Nasi Qafzezi was killed. The second blow was the death of his 23-year-old son, Ganiu, on July 2, 1914, in a clash with reactionary forces. Sali composed a lament for him: “The mountains of Gramoz weep for Gani Butka who was slain,” a song that remains a staple of gatherings in Southern Albania.

The Surgery without Anesthesia

When Greek massacres began in the south in 1914, Sali and thousands of refugees fled to Vlora. An old eye injury from Nikoliça had become unbearable. His friends urged him to go to Italy for surgery. He boarded a cargo ship to Bari, where Albanian immigrants helped him reach a renowned clinic.

When he entered the operating room, the doctor insisted on using anesthesia to put him to sleep. The “Old Man” refused.

“I don’t know what I might do while asleep,” he said. “What if I lose control or bellow like an ox in the middle of Italy and shame myself? Can you do it without medicine?”

The doctor insisted, but Sali was as stubborn as a mule. The surgery was postponed. After a second consultation, his request was granted. The operation was performed without anesthesia. They placed the removed eyeball in his hand. Not a single sound escaped his lips; only beads of sweat rolled down his face, pale from pain. The following day, the newspaper “Corriere della Puglia” ran a front-page headline about the Albanian who underwent surgery without anesthesia.

“No one would have submitted voluntarily to such a case; one must be Albanian, one must be brave and courageous to do such a thing,” the paper wrote. The event drew journalists and surgeons from across Italy.

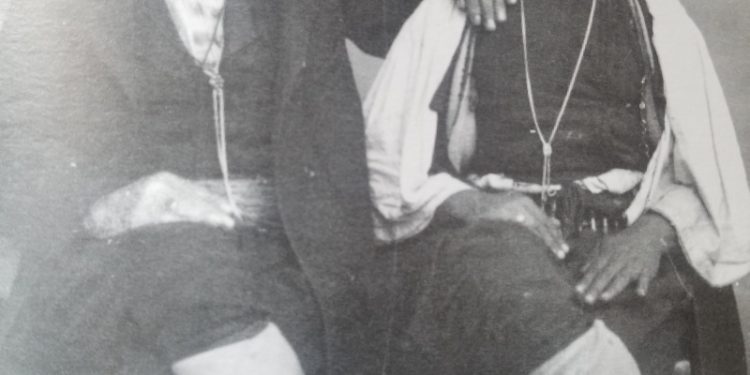

The Clever Peasant and the French “Checkmate”

Sali Butka used a tactic similar to Kutuzov’s against Napoleon. In 1916, when the French were considering handing Korçë over to the Greeks, Sali surrounded the city. When a French representative came to negotiate and spy on his strength, Sali ordered his 5,000 men to move in a loop – appearing, disappearing behind a hill, and reappearing. The Frenchman calculated that Sali had at least 12,000 certain troops.

Convinced of Sali’s “massive” army, the French officer telegraphed Thessaloniki, and the message traveled all the way to Paris. The reply came back: “Korçë belongs to the Albanians.” Thus, the “Old Man” protected Southeastern Albania from Greek annexation.

The Ultimatum

In August 1919, during one of Albania’s most critical moments, the French again prepared to hand Korçë to the Greeks. Sali Butka gathered 1,500 volunteers in Gjergjevica. In September 1919, he issued a 14-point ultimatum to the French command:

Ultimatum in the Name of the Albanian People

“Commander, unaware to the French people and against our will, your diplomacy… has pronounced the death sentence of the Albanian people by handing Korçë to Greece… We find ourselves forced to warn you: hand over the city of Korçë and its surroundings within 48 hours…”

Gjergjevica, September 1919 – Commander-in-Chief Sali Butka

The Final Chapter

After his battles were over, Sali returned to Butkë to rebuild his homes from the ashes. He lived his final days quietly, remembering his sons left on the mountainsides. He was briefly arrested during the Fier Uprising under Zog’s regime but was released as he was by then just “a handful of bones.”

Before his death, he hired two stonemasons to carve his headstone with a sculpted eagle. He sent them back twice until the design was perfect. He died on October 20, 1938./Memorie.al