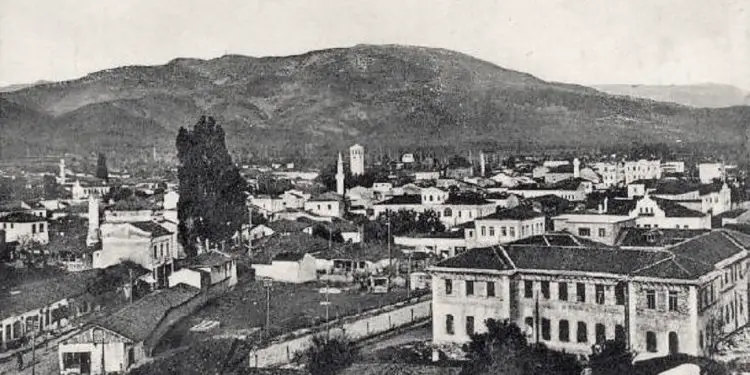

Memorie.al / “I was born in Elbasan on March 8, 1902. My father, Emin Haxhiademi – whose patriotic activity began as early as 1877, meaning before the League of Prizren – is known as a close collaborator of Kristoforidhi and the second oldest patriot in this city after him.” Thus begins the biography of Et’hem Haxhiademi, the first Albanian playwright, recounting the beginnings of a life that was both furious and definitive for his later work. Upon meeting the surviving members of the Haxhiademi family, a photograph of the man who left an indelible mark on Albanian literature catches one’s attention.

His European attire, stoic posture, and especially his gaze are the elements that distinguish him as a man who would bring so much, but receive so little from a stubborn life. With hesitation, his brother, Selaudin, recalls those few moments spent with him, bringing to mind the grim period of his imprisonment, which marked his death at the age of 63.

According to witnesses and official sources of the time, his death was the result of a heart attack; however, how true this was given the nature of the dictatorship – where people vanished so easily – was never confirmed, leaving the death of the downtrodden Et’hem Haxhiademi an enigma.

Childhood and Life

Childhood would decide everything for his future – simultaneously bright and bitter. This was confirmed by Et’hem himself in a manuscript sent to Lasgush Poradeci, titled: “Notes on My Life.” As a student in the first class of the newly opened “Normale” school, he recalls the first Albanian books he read, privileged by his father, who possessed all the magazines and newspapers of the time in the Albanian language.

Being the son of a prominent patriot and one of the founders of the “Normale,” Et’hem would be the first to be registered at this school. “I learned the Albanian language from my father,” he states, “since before the proclamation of the Young Turk Revolution (Hyrrieti), being the first student of the Albanian school in Elbasan in 1908.” The existence of a telegram sent by the great Faik Konica proves this historical fact, though it was never acknowledged by the regime in power.

In 1919, he began his high school studies in Lecce, Italy, but the exam period proved unfavorable for him, as Albanians were being pursued by the Italians due to the Vlora War. Yet, Et’hem managed to resist the pressure, being the only one among many other Albanians who was able to pass the grade. Afterward, Austria awaited him, where he would continue the completion of high school and the study of the works of Greek tragedians in Latin and German.

In 1924, he was in Berlin, continuing his university studies in Law – as he says, against his own will, but according to the wishes of his parents. The polyglot from Elbasan never for a moment forgot literature in various languages, especially from the ancient period. During his stay in the German capital, tragedy suddenly became a part of his life. The girl he had fallen in love with died, marking a blow for the young Et’hem, who in 1927 returned to Albania and, a year later, was appointed sub-prefect of Lushnje.

In 1933, he was in Gjirokastra as the chief secretary of the prefecture. At this time, it was Zog’s monarchy leading the country, and the King himself held high regard for Et’hem’s preparation. It would be exactly this time – despite Et’hem never involving himself in politics – that would decide his fate. During the Italian occupation, Haxhiademi remained indifferent, participating in no movement, but in his thoughts, the Balli Kombëtar movement was considered just.

It was his stance during the fascist occupation that decided his imprisonment in Burrel Prison during the communist dictatorship, which caused so many problems for his family. His sudden death was determined to be a heart attack, even though Haxhademi had never suffered from such conditions. This is precisely where suspicions of a possible murder arise, but according to the family, this was never proven.

The Tragedies

A few old books and some newspapers of the time would provide Et’hem with the sustenance of the Albanian language. “They were poor,” Et’hem states in his correspondence, “but for us, they were very rich, and my father kept them in a special room where I read them in secret.” Perhaps this is where the love for the book and especially for drama was born, of which Et’hem read very little in his childhood, but it was deeply marked in his soul, thus writing his future.

The drama translated from Turkish, “Besa,” by the great Sami Frashëri, would be his first sustenance of drama in Albanian, and drama in general. Speaking of the drama “Besa,” he states that its lines and emotions were so great that he locked himself in the room that was also the shelter of books to finish it. The impressions of this drama were such that, at the age of 14, Et’hem decided to write his first drama as well.

“One day I sat at a table and began to write a drama, naturally with a national subject, as was the spirit of the time. I stayed for days on end, sometimes even leaving school without attending. When the people of the house asked what I was doing, I wouldn’t tell them. In the end, after about two months, I finished the drama and showed it to my father, who was capable of judging it.” But his stern and very determined father did not accept the idea that his son could write such a difficult genre and told him that it was laughable and deserved to be burned.

Obeying his father, Et’hem decided to burn that drama, but not the desire to write dramatic works. While studying at the high school in Lecce, he read Virgil’s “Bucolics,” a work he decided to translate when he learned Latin well. And indeed, his determination had no end. After three years, Haxhademi, now prepared, translated the “Bucolics” from the original version into hexameter, something that none of the well-known writers had done until then.

There is no lack of appreciation for him here, as for the time, no Latin work had come into Albanian, and especially no writer had been able to use the hexameter. During his higher studies in Berlin, with his great love for ancient legends, Et’hem managed to treat his first tragic work, “Ulysses,” which was fully the spirit of Aeschylus, after thousands of years. Tragedies held the heart of the young Haxhiademi and could play with it.

In his manuscript, he also lists his favorite writers, especially the ancient ones, but does not forget to appreciate colossi like Shakespeare. The next work would be exactly one of the stoic characters of the great Greek tragedy, “Achilles.” He would then continue with other tragedies, such as “Alexander,” “Pyrrhus,” and “Skanderbeg,” which, by following the rhythm and the misty veil of Greek tragedy, brought them to our days and especially under the Albanian cloak.

Literary Correspondence with Lasgush

Haxhiademi: “Tragedy is my spirit of living”

In the next correspondence, Lasgush had asked Haxhiademi for his works, and the latter had gladly sent him several of the many lines that never saw the light of publication. A life full of suffering and a personal tragedy brought by the death of his beloved in Germany made Et’hem write not only tragedies but also elegies, which ranked him as an elegiac poet. An elegy under the title “Galates” brings the poet’s pain for his lost love, for his beloved girl.

He was in Albania now and sang to her in the language of the famous Greek tragedies. “The Nymphs of Shkumbin” was also the work that brought antiquity to the Albanian literary river. “The beautiful nymphs continued to bathe in the river water along the Albanian lands, and the hunters, not understanding the value of their song, ‘abduct’ them. Is this not an Albanian occurrence?” – he continues the letter addressed to Poradeci, from the forgotten name of Albanian tragedy, Et’hem Haxhiademi.

But the mother, too, as an always beloved and compassionate portrait, comes into the writer’s elegiac verses upon her death. “Black Night” (Nata e Zezë) would also be a lament for his mother, whom Haxhiademi defines as the person he loved most in this world. Even an ode for Naim Frashëri was not missing from the literary activity that would mark his life.

“Briefly, as per your request in ten pages, this is my artistic life. In the letter you sent, you gave more importance to lyrical poems. But for me, the greatest significance lies in the tragedies,” concludes the letter of the tragedian who dared to challenge the greats of antiquity and who throughout his life never forgot his passion for tragedy, something for which, as he says himself in his correspondences and memories, he was “kneaded.”

The Testimony of Selaudin Haxhiademi regarding those few moments with his imprisoned brother

It was precisely Selaudin who, with his silent and short-spoken nature, defines his brother while protecting him from distortions and seemingly favorable assessments. According to him, many of the works were destroyed by envious people, and often his fate was sealed by the ill-intended. “The great remain great, and his assessment cannot be a favor,” he continues, “We do not want superficial assessments. In the few moments I knew my brother, I realized he was a man who had not thought of profiting or escaping situations.

When we met him in Burrel prison – the four children and our mother – he asked us to remain silent so as not to be worried for him, and especially not to write him anything, as the correspondence never reached his hands. The only moment his fellow prisoners in Burrel remember was the day of Fan Noli’s death.”

According to him, Noli must have been older than 83, as he could not have been ordained a priest at the age of 23. The monist regime itself, by imprisoning him, managed to exploit his translation, to which he was devoted more than anyone else, especially regarding ancient works. Many of his translations during prison have either taken another name or were not published by the monist dictatorship.

Having studied in Western countries, Haxhademi was a man of broad knowledge even regarding politics, but he did not involve himself in any of the movements, staying away from the war and especially far from the communist movement. This harmed him greatly, bringing prison and death. He received no decorations, he was not recognized, while his brother passed away very soon, also from a heart attack.

Emin, following his brother’s path, also became a mayor during the time of democracy. Great but forgotten is how literary critics have defined the name of Et’hem Haxhiademi, one of the pure figures with unimaginable values, as he dared to cultivate tragedy, yet was the most unfortunate among Albanian writers, suffering the tragic fate: death in prison. / Memorie.al