Part Six

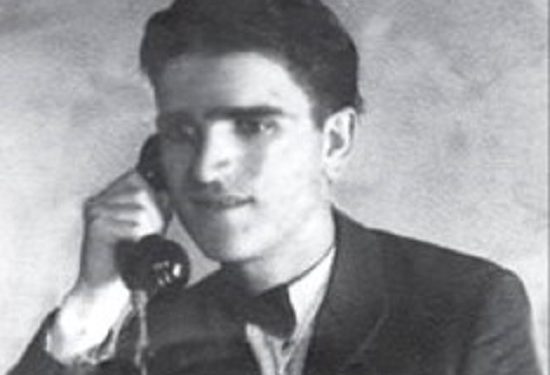

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, a Library of Noble Wit’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / Whenever we, Alizot’s children, told “Zote’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social gatherings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No? What a shame, they will be lost…! Who should do it?” And we felt increasingly guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones to do it. But could we write them?! “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zote used to say whenever he leafed through poorly written books. When we, his children, discussed this “obligation” regarding the Book, we naturally felt inadequate to fulfill it. It wasn’t a job for us! By Zote’s own “yardstick,” we were incapable of writing this book.

To be continued from the previous issue…

IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT EMIRI

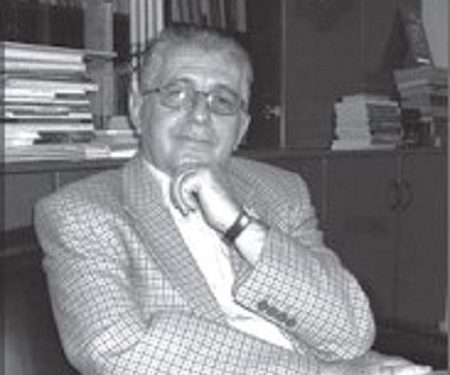

By Prof. Dr. JORGO BULO “I CANNOT COPE BY WEEPING, BUT BY SINGING” (My noble friend, Alizot Emiri)

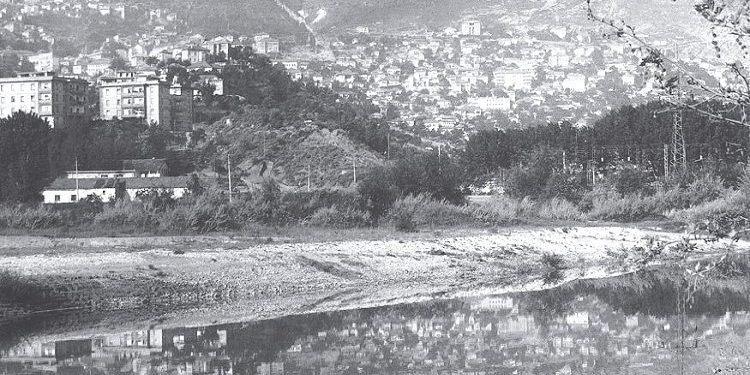

I lived in Gjirokastra for 13 years as a high school teacher, and for all those 13 years, Alizot remained among the most heartfelt and wise people I knew. His daily work, which supported his family, was surrounded by the culture of the books he sold. But first and foremost, he possessed a cultured soul. He did not care for the state of that era, and his reasons were generally above the level of the ordinary people around him. This coldness toward the state resided within his soul, seemingly unreadable. It wasn’t found in insulting words, but in a dismissive silence, which for him was also a sign of nobility.

In that environment of state oppression and the common psychology of the people around him, to hurl insults was like walking on a muddy road from which you emerged barefoot, or like holding your mouth open toward the sky, waiting for stars to fall like candy! Heroism to the point of sacrifice was something else entirely, meant for different circumstances in his view. Alizot was at peace with himself – silent with officials, approachable with people, and full of humor with trusted friends. Thus, his life passed surrounded by books containing all the wisdom of the world.

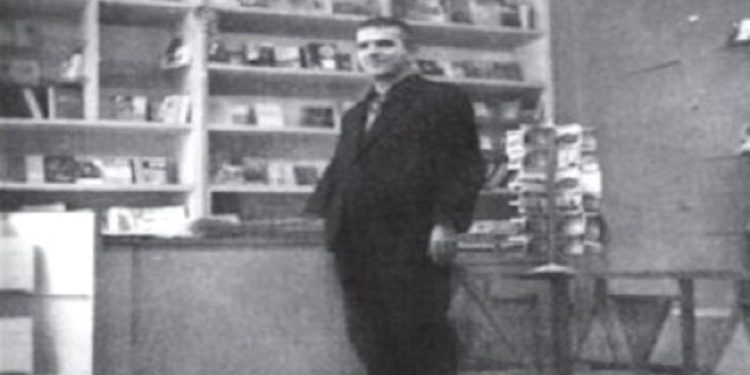

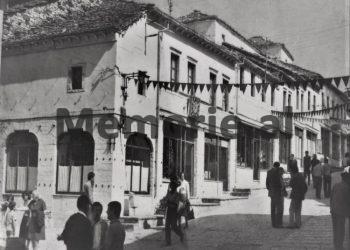

I had his three children as students, each better than the last, and they provided more opportunities for me to meet their father. In his bookstore on the city’s central street, the parade of people walking to their business passed naturally before his eyes. He did not interfere in their lives, yet through them, he could sense the city’s spiritual pulse. Some climbed upward as if going to a wedding, others descended as if toward a graveyard… Life moved the same before his eyes, while he remained dignified – at times the “trouble-bearer” of the day, at others the philosopher of an undefined era for that city.

There, heading up or down, I would also walk with my teacher’s bag tucked under my arm. His sweet face behind the glass windows invited you to enter. I would go in with the certain pleasure that I would hear something new and wise. Even before he spoke, his face radiated sincere kindness and humor. Among the books that filled the shelves, he was a “book” in his own right, wandering among them to arrange them better and to subtly place them into the hands of those who entered. Many bought a book out of shame, for to return it in front of others was considered a blow to one’s manhood!

Humor was the first thing on his lips. He lived in a city where people, in their simplicity, possessed kindness, while the state produced malice. Since he could do nothing against that malice – which could drag a victim all the way up to the castle prison – he burdened it upon humor so that people, as if without his intent, could read the situation more clearly. It was a city where a porter’s pack-saddle was more human than the Committee’s “Gaz” (Soviet jeep).

At Alizot’s, you could learn these things accurately. Of course, he knew who he was talking to. From the street, he appeared through the glass sometimes like a dark surrealist painting, sometimes like a master of the house tending to his books, speaking to each by an intimate name. With intellectuals, he was serious and cultured. With the little ones, he would lean down tenderly, like women scattering crumbs for birds. He would show them the pictures in their books and explain them briefly. He watched those who entered aimlessly with an eye of pity. Someone would walk in with bags from the bazaar, and he would first humorously ask about the prices! Someone once accidentally dropped a banknote, and Alizot pleaded with him to pick it up, claiming his wife had taken the broom home that day!

When a cooperative chairman entered, his eyes fixed on Walt Whitman’s book of poetry, Leaves of Grass. He was examining it closely because winter was coming, and he was responsible for securing livestock feed. Alizot watched him from the corner of his eye.

“That grass – why is it only ‘leaves of grass’ and not full-grown grass, the kind our livestock needs?”

“Because it is select grass,” Alizot replied.

“Where does it grow?”

“In America, but the book teaches you that such ‘grass’ can grow here too. It’s good for children!”

“I don’t follow you,” the chairman replied.

“Buy it for the schoolchildren, and they will learn, for themselves and for the livestock. Once you’ve read it, come back and tell me! Tell the other cooperatives too!”

He didn’t argue further; he bought three books, looked once more to see if he could clearly distinguish the blades of grass on the cover, shook his head indecisively, put them in his bag, and left.

“What will you do when he finds out what’s inside?” I asked my friend.

He laughed: “You heard me, I didn’t lie at all; it is good for the students. Besides, sometimes these folk need it this way! When they don’t know how to judge, why are they in such a hurry to speak?”

He told me another story: “Yesterday, the Chairman of the League, Shuteriqi, came by. His book Kënga në Minierë (Song in the Mine), written while he was stationed in Mirdita, has turned yellow from the summer and wrinkled from the winter. No one buys it. The author entered with two officials. I pretended not to recognize him. He saw his books on the shelf, didn’t like their condition, and suddenly asked me just to pass the time: ‘How is business?’

‘Nothing much,’ I replied, ‘The Song in the Mine has left me stuck at the door!’ I stayed serious, acting ignorant. He turned his back and left.”

An official later rebuked me: “Don’t you know who that was? You insulted his book!”

“I am not the civil registry to know everyone who enters here! Besides, it is up to the book whether it praises or insults its master! I am Ali-Zoti (Ali-God) for myself.”

He laughed to himself again. “It’s 12 o’clock. Come, let’s sip a coffee!” He closed the shop and we went out.

“Your humor never runs dry,” I told him, “where does it come from?”

“From your Lab song that I love so much: ‘I cannot cope by weeping, but by singing.’ In that polyphony, it’s as if my soul has found its shelter.”

He never asked me how his children were doing in school! But one day he said anxiously: “I have a wonder or a worry: it seems to me that national history, the deeds of our ancestors – especially against the Greeks at our border – are being taught to the children in a truncated way! I cannot understand why in the gymnasium, history is only taught by Greek teachers, one after another. Who is orchestrating this?! You see it yourself, you are close to it! I asked my child one day about the Greek occupation of Gjirokastra in 1940, how they lowered our flag and raised theirs. The child’s eyes went wide, as if hearing a fabricated dream!”

Then he added: “I fear that even if they do well in their finals, the scholarships are still commanded by a Greek, strangely hidden behind the surname ‘Çami,’ as if attached by someone! Anyway, others know these things and they will solve them themselves,” he concluded his concern with wise neutrality. Surprised by his observation, I shrugged and searched my memory!

“I didn’t tell you this so you’d bring it up in the Pedagogical Council,” he added humorously, “because as a Lab, you might just fire it off like a shot!” He laughed sincerely and ordered another drink.

As instructions came from above, havoc was wreaked against religion and its places of worship. Suddenly, a roadside tavern brightened its sign, writing “KAFE” (Coffee) in beautiful calligraphy. But since the stone was narrow, they wrote “KA” on top and “FE” below, so from a distance it read: “Ka – fe” (There is – faith/religion). The owner who did it was summoned by the Party, then the Sigurimi (Secret Police)…! The most fearsome Secretary of the Committee, with terror in his nearly white eyes, went to Alizot and, after glancing at some books, said:

“The word ‘Zot’ (God) in your name is against the Party line! How can you still keep it in this revolutionary spirit? You even have smart children in the gymnasium.”

Alizot, found in a tight spot, replied calmly: “I am not to blame for my name, Comrade B.; my parents gave it to me when the Party hadn’t been born yet, and my father hadn’t foreseen this! But I have a question: Is the word ‘Zot’ (Lord/God) equal to the word ‘Zonjë’ (Lady)?”

Without realizing where this was going, the secretary affirmed: “The same: ‘Zot’ is male, ‘Zonjë’ is female.”

“In that case,” Alizot added calmly and politely, “if the Heroine ‘Zonjë’ Çurre has her name changed, I will change mine right after her!”

The secretary found no words to respond, snorted rhythmically as was his habit, and left, muttering an angry reply to discuss with his comrades.

The Leader of the country arrives in the city. With a luxury cane in hand, Enver Hoxha walks slowly through the city’s cobblestones, surrounded by officials of every kind. The sidewalks were filled with people, most watching him with pride and adoration, others with curiosity. When he saw someone he knew, he would meet or greet them, depending on his memory of each. Alizot stood in front of his bookstore. As soon as he saw him, the Leader called out in the local dialect: “Alizot!..”

That was all he needed, and he set off through the crowd to meet him.

They embraced, and then Enver asked about his children and his work. To every question, even if things weren’t great, Alizot said only: “Well.” Photographers were capturing them in dozens of shots from all sides and in full color. Finally, Enver asked him once more: “So, you have no troubles then!”

Smiling slightly, Alizot replied with an intimacy he allowed himself: “Now that we’ve been seen together, Comrade Enver, for a while, I won’t have that many troubles.” He smiled, and they parted.

Whenever I go to Gjirokastra… I instinctively turn my head to the right, as if expecting to see Alizot Emiri in his bookstore… He was not simply a “bookseller,” but an institution.

I must have been in my first year at “Asim Zeneli” high school when I entered the shop… He pulled from under the counter the 1926 edition of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat and told me:

“This is not a book for sale; read it and return it when you’re done. You will like it.”

He showed me trust… he had the rare intuition to recommend to everyone exactly what they needed. Alizot Emiri remains unforgettable… a rare book of folk wisdom. I hope his sons preserve not only his memory but his spirit./Memorie.al

Tirana, February 2011

Continued in the next issue…