Part Three

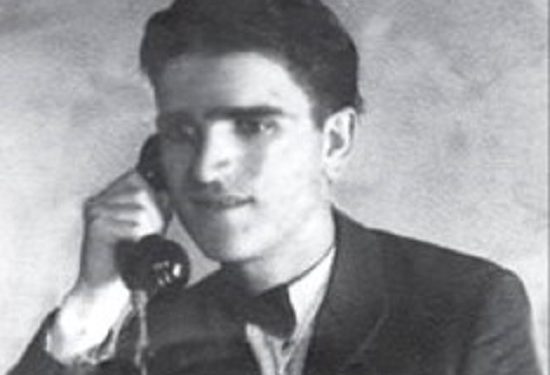

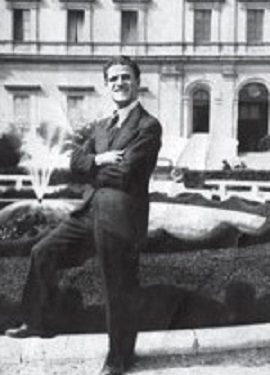

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, the Bookseller, and the Noble Journalist’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Memorie.al / When we, Alizot’s children, used to tell “Zote’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, we were often asked: “Have you written them down? No! What a shame, they will be lost… Who should do it?” And we felt increasingly guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones who should do it. But could we write them? “Not everyone who knows how to read and write can write books,” Zote used to say whenever he handled poorly written books. As we, Zote’s children, discussed this “obligation” – this book – we naturally felt our inability to complete it. It was not a job for us! By Zote’s “measure,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Continued from the previous issue…

IMPRESSIONS AND MEMORIES OF ALIZOT

A conversation with the prominent writer Dritëro Agolli

Dritëro Agolli shared these impressions and memories with us when he fulfilled our wish by inviting us to his home on January 22, 2011. We felt very good seeing Dritëro recounting with pleasure and laughing constantly while portraying our father’s personality.

We had heard our father speak with high regard for Dritëro as an outstanding writer. He recalled their beautiful, humor-filled meetings with great pleasure. Zote particularly valued Dritëro as a man who, despite his high social status, remained humble and knew how to respect people. Alizot felt highly respected and valued in Dritëro’s company, which brought him special joy.

Our mother, may she rest in peace, who lived many years after our father’s passing, used to remind us and plead with us to find an opportunity to meet Dritëro, have a coffee with him, and thank him on behalf of our entire family for the respect he had shown toward our father, Alizot Emiri, during those difficult times. We thanked Dritëro with deep gratitude for fulfilling this wish.

We believe he also enjoyed our presence in his home. He welcomed us alongside his wife, Sadie. They hosted and honored us as the children of Alizot Emiri – as the children of a friend! Dritëro’s granddaughter and grandson took photographs of us – a special memory. With his approval, we recorded the entire warm conversation on a dictaphone. We also told him some of Zote’s stories. He laughed from the bottom of his heart and, after every story, repeated his praises for Alizot’s wisdom, finesse, culture, and especially his clever and kind humor.

ALIZOT WAS MY FRIEND

The first part of the conversation with Dritëro, January 22, 2011:

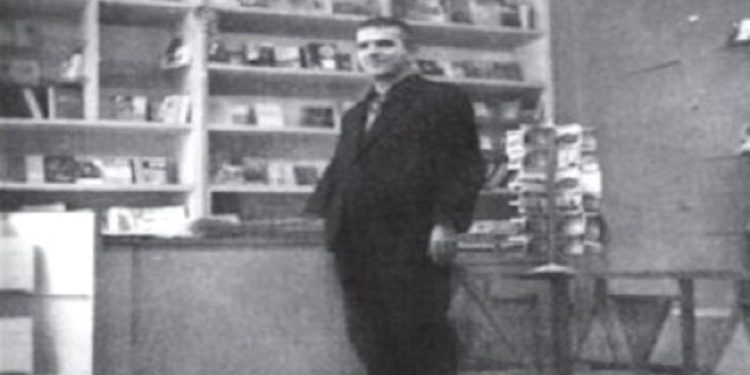

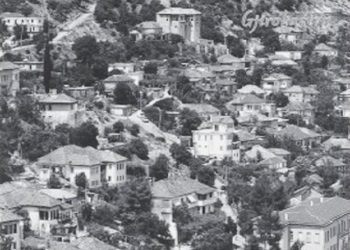

In Gjirokastra, no matter where we wandered, we always ended up at Alizot’s bookstore, located at the “Qafa e Pazarit” (Neck of the Bazaar), on the left side as you went up. He kept a very good bookstore, but he also drew people in.

I valued Alizot highly, and when I met him – as I often visited Gjirokastra on business back then – I felt great pleasure because he was very pleasant in his words and conversations. He knew a lot from his life experience in general, but also a lot about history and books because, as the old folks say, he was a “well-read man.”

He had a subtle humor when he told stories – the kind of humor belonging to a high intellectual. It wasn’t vulgar humor; it was rare. Generally, the people of Gjirokastra at that time were humorous and possessed originality in that field. Whether at the table, in cafes, or homes, humor was never absent. Alizot had mastered this from daily life. He knew history very well, read books, and knew all the historical events of Albania – both ancient and contemporary.

In a word, he was an entire encyclopedia. Perhaps because of this wisdom gained from both life and books, he was so pleasant in conversation that you never got bored staying with him. He didn’t repeat things; he hated retelling them.

Particularly, what impressed me then was his certain disdain for those who didn’t behave well, who promised much but did nothing. I remember once while on service in Gjirokastra, many Marxist-Leninist books had been released, and the series of Enver Hoxha’s volumes had also begun.

-“You have quite a lot of these,” I said when I entered the bookstore.

-“My friend, I had even more,” he said, “but I went to the Party Committee, placed them on the desk of every instructor and party worker, and told them: these are the books you must know because you are Marxists and you must explain them to the people. You don’t take a single one of these books. Rarely does someone take one, yet you never come to my bookstore to browse or leaf through a book. Therefore, I am giving these books to all of you; collect the money and bring it to the bookstore. I cannot give them to you for free; perhaps the authors, Marx or Engels, could. I took them to sell, so I am bringing them to you instead of you coming to get them. And I sold all of those,” he said. “I also went to the Executive Committee and sold them there too. But I have a few left; I’ll take those there as well so they have them. Thus, slowly, these political books are selling. I take literary books because people are more curious to read them. Here, for you – if you haven’t already gotten it in Tirana – I have an old book; you’d do well to take it.”

I took it and still have it in my library today. From this fact, I thought one day: this is how a bookseller should be. He must know the books he has, know their content, and be able to say: “this is useful for you.” Today there are all kinds of books for all professions, but booksellers are not like the booksellers of old, like Alizot.

Then Alizot said to me: “Shall we go ‘sip’ a coffee?”

– “Fine, let’s go,” I said. “Let’s go to the plane tree, to the Hunters’ Club.”

– “Old men go there and they will bore us,” he told me. “Better we go to Cile Muka.”

Cile Muka had his own tavern; he was a man who looked after other things but did so with mastery, so both of them were masters. At that time, I had published in ‘Zëri i Popullit’ the line: “I have Cile Muka nearby and culture right across.”

We had a coffee and a glass of raki. Cile placed another glass in front of us, and Alizot said to him: “What got into you to set me on fire?!” From that time on, whenever I went to Gjirokastra, I would ask my friends: “where shall we ‘sip’ it?” – as Alizot used to say – or when they placed another glass before me, I’d say: “What got into you to set me on fire!”

Once I was at Zote’s bookstore during the Gjirokastra Festival, and folk groups were marching up from Qafa e Pazarit. The large drums of Dibra and Tropoja were beating so hard that even the books shook from the thunder.

-“Well, Zote,” I asked, “how does this joy seem to you?”

-“Very good,” he said. “All the rats of Gjirokastra will flee; not a single rat will remain. From the noise of these drums, they will flee to Libohova, they will flee far away, and this is a good thing for us because every five years, Gjirokastra gets cleaned of rats…!”

He told it so beautifully. I repeat it, but the repetition lacks the nuances it had when he told it himself. There are plenty of stories, and they are beautiful, not vulgar; they are cultured and do not offend. Agim Shehu told me how he once asked Alizot:

– “Where are Basho Thomai, Ramiz Harxhi, and Lefter Dilua? Where are they?”

– “There, they are descending Qafa e Pazarit singing the national anthem,” Zote told him, for they were his friends and he joked with them, as to Alizot, they were like new patriots and “Rilindas” (National Renaissance figures). Alizot was a man of great humor.

He told us that in Gjirokastra, when Enver Hoxha once came, he saw Alizot at the bookstore door, met him, and embraced him. Alizot was very happy that people saw Enver embracing him, because in Gjirokastra there were some people who reminded him of his biography, telling him that in the 30s he had written this or done that (since Alizot had also been a journalist, writing for the newspaper “Demokracia”).

Alizot was a clever man of great culture – not just ancient culture, but also the new culture after WWI, WWII, and the National Liberation War. He knew the most interesting places in Gjirokastra very well, but he knew even better how to give advice. For example: “this building is decaying,” or “this castle wall has defects from time.”

– “Come, let me show you,” he said to me one day. “See how grass and figs have sprouted in the wall? These will grow roots and this wall will fall, but they don’t listen to me; they tell me this grass holds the wall up. They are fools, for this grass sends roots deep inside.”

My point is that he was interested not only as a man of books but also in the environment, the city’s cleanliness, and the cultural monuments of Gjirokastra. When we were students in Gjirokastra, those monuments were standing, they were good and beautiful. Recently, since no one looks after them, a large part of them has been destroyed, and it is a tragedy…!

If we had people like Alizot today, the appearance of Gjirokastra, the bookstores, and everything else would be different. You are doing well with this book about Alizot, and you should collect other memories too, for there must be elderly people in Gjirokastra with many memories of him, particularly of his rare words.

On February 9, 2011, I went to Dritëro’s house to show him the edited transcript of the conversation we had recorded. They welcomed me like a son of the house. Mrs. Sadie came to the door; Dritëro stood up as if he were about to meet Alizot. I felt more respected than I deserved.

I gave them a symbolic gift: a CD of the piano concert performed at the National Theater of Opera and Ballet on January 28, 2011, by Alizot’s granddaughter, the pianist Almira Emiri, accompanied by a brochure of the program and her CV. They were delighted.

Mrs. Sadie brought glasses of raki.

– “After you called,” she said, “Dritëro has been pensive the whole time, recalling his acquaintance with Alizot. This brought him joy, because knowing him belongs to the beautiful times of Dritëro’s life. Today he got up at dawn and sat down to write about Alizot again. Dritëro cannot write by hand easily now because it trembles a bit, but for this piece, he mastered that ‘disobedience’!”

She placed the page handwritten by Dritëro before me.

– “I will make a photocopy of this manuscript so you have a memory from Dritëro’s hand,” Mrs. Sadie said.

– “Now you will continue writing what I say!” Dritëro told me. And we continued putting his thoughts on paper: He spoke, and I wrote.

– “I felt uneasy,” he said, “that in our first conversation, we didn’t draw some conclusions about Alizot. For Alizot was no ordinary man!” Just as we finished writing, I asked them to look at the “introduction” that Ibrahim and I had prepared. I read it to them. They listened until the end.

– “You have done it very well,” said Dritëro, receiving Mrs. Sadie’s approval. “You can place it at the beginning of this conversation, but remove that epithet ‘simple’ (humble) that you wrote for Alizot!”

– “But Alizot was a simple man!” I insisted.

– “You are wrong!” Dritëro corrected me. “There are no ‘simple’ people; that are a term left over from old times. A human being is very complicated. And Alizot was not an ordinary man! He was a man of knowledge, of wisdom…” / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue