By Agim Janina

Part One

Memorie.al / Acquaintance with Ibrahim Kodra came as it does with any artist. Initially, you happen to hear about him and his work, and later you are given the chance to meet him. The artist lived in Italy and news about him was scarce, but in meetings with contemporary painters, his name was rarely mentioned. His works were unknown. It was whispered that they were “modern.” In the National Gallery, there was a landscape of Tirana that few had seen. The fame of the painter’s name arrived vaguely, intertwined with legends and truths. It was known that he was from Ishëm (some believe the name means “the handsome/graceful one”), where he spent his childhood, while his early youth was spent in Tirana. Having left for Italy, he was the “great absentee.” While researching the Drawing School, his name was present in every conversation held with his contemporaries.

“People’s Sculptor” Odise Paskali, one of the founders of the school, recounted that Ibrahim Kodra was initially at the Technical School and wanted to become a painter. He was expelled from the Technical School. “I went to the Ministry of Education and begged them to take him into the Drawing School. – ‘We are surprised by you, Paskali – they told me. – We are kicking him out as an undesirable element, and you want to take him into your school’?!

‘Ibrahim does not want to become a mechanic. He has the soul of an artist; he paints cinema advertisements. However, the public sees the advertisements, and through them, Ibrahim addresses the people, guiding their taste. If he comes to the Drawing School, he will paint better and make the cinema advertisements more beautiful.’ They were not convinced and did not allow me to take him as a regular student. Nevertheless, he came often and painted.”

Hasan Reçi, Sadik Kaceli, Foto Stamo, Nexhmedin Zajmi, Qamil Grezda, Kel Kodheli, etc., had been classmates and later separated into different schools in Italy. They went to the Academy of Rome and Kodra to the Brera Academy, which would define their artistic paths and fates, which were entirely different: the former became staunch realists, returned to Albania, and submitted to the movement of Socialist Realism.

Kodra followed the modern trends of the time, exhibiting in famous galleries in Italy and abroad. In an exchange of letters between him and Zajmi, when the latter had sent him a postcard with a reproduction of his work titled “The Drin Dam,” depicting several workers building the Drin hydroelectric power station, Kodra replied: “I searched all over Rome, but I could not find such workers anywhere!”

Zajmi had written to him that these are the workers, this is art, this is how one paints in Albania. The painter’s first return to his country took place in 1973, and the people who met him were timid; although he traveled everywhere, he did not exhibit any work, gave no interviews, and did not speak about his art.

His opportunity came after the arrival of democracy, where he freely met colleagues, friends, and many art lovers, even holding a solo exhibition. It is not that he received warmth from all Albanian artists – which hurt him – but the curiosity to know him was great. From one of the meetings with him, from my personal archive, we are presenting the following conversation, conducted in July 2003.

One evening, we met the artist Ibrahim Kodra near the National Gallery of Arts, waiting for the opening of his solo exhibition. In the garden in front of it, a small buffet was set up, where coffee and drinks were served at several tables placed around. Along with the painter, several artists and Gallery employees gathered.

Inside, the painter’s works were being arranged, and he entered and exited from time to time. The Master was accompanied by Renzo Calzavara, a painter and close friend. Meanwhile, during the conversation, viewers and art lovers approached to listen to the great artist.

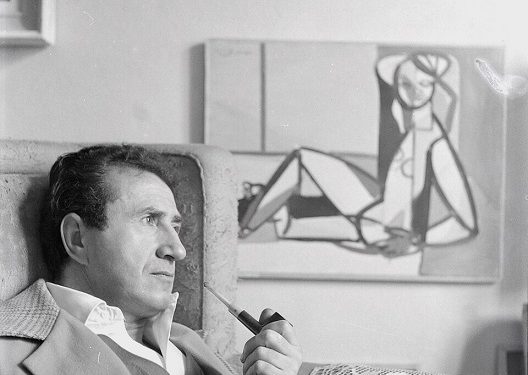

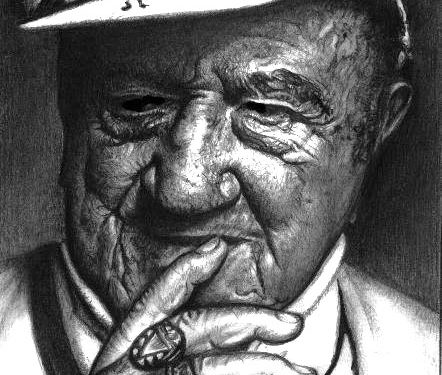

Kodra wore his characteristic cap, this time in white with thin checks; a smile lingered on his lips, while his eyes in his wrinkled face sparkled with kindness. Despite his advanced age, he showed vitality in conversation, though questions often had to be repeated as he had begun to lose his hearing. He answered slowly with a slightly raspy voice, sounding as if speaking through his nose. During the conversation, he often used words in Italian or French.

As soon as he arrived, he sank his bulky body into a rubber chair. On his large hands, several rings shone brightly on his thick fingers. He kept his mouth slightly open, and his lower lip seemed to hang down, revealing his dentures. From under his cap, a few strands of hair dyed in a reddish-brown color emerged.

In his youth, he had been a powerful boy with the toned body of an athlete and had been declared a javelin champion. Several photos from that time showed him handsomely, but a later accident when he fell from a horse caused him to drag one leg slightly when he walked. It was clear he felt good in the cool of the evening, which was evident in the delight on his face.

– “Let them shake the hand of the painter who smells of Albania,” – I spoke.

He gave me his hand but did not move, as if my presence had made no impression on him. Someone reminded him of his childhood years, and he began to recall when, together with Kaceli, Stamo, Zajmi, Grezda, etc., they made their first wanderings on canvas and when in the afternoons they went to swim at the Brari Bridge. Suddenly, he also mentioned the visit that the three Albanian sculptors Kristaq Rama, Muntaz Dhrami, and Shaban Hadëri had made to him in Milan during their stopover on the way to Paris. “We could not go to Paris without meeting the great master Kodra,” the painter would recall Kristaq Rama’s words.

With emotion, he recalled an “incident” in a restaurant in Milan, when as Albanians, after eating; they were “fighting” over who would pay. Kodra, with his Great Spirit and characteristic gentleness, would say: “Be silent, for the lunch is paid for. I gave the owners of the place a painting, and I have the right to eat 1,000 lunches!” – he fell silent as if moved, and continued as if lost in memories:

– “My mother left me when I was three. My father remarried to raise me. My stepmother gave birth to a son. We named him Qamil. When my father died, six months later, my stepmother married again. ‘I cannot go with you; I will stay with my brother!’ – Qamil told her. He loved me very much. He had finished the Agricultural School in Kavaja. They killed the poor soul. The house was beautiful with a yard, a large garden, and a well with sparkling water. I grew up with a well. We had all kinds of figs, apples, pears, and centuries-old olive trees.

– Did you start drawing in Ishëm?

– “My father brought me a block of paper and taught me to write my name in Turkish. While playing, I filled the block. And so it comes naturally to draw the house, the sea, the mountain… and thus slowly the inspiration comes, it grows…”!

– “You have also written poetry,” – a young student who had just sat near us and was listening with curiosity interjected and asked.

– “I have written twenty poems. The first poem I wrote, which spread everywhere, is the poem for my mother. When I read it, everyone cried. I have recited it many times.

After finishing primary school in Ishëm, I came to Tirana to Harry Fultz’s Technical School, where Daniel Ndreka taught me, but there was also Professor Dajçi. Painting was a tool of work. I have always been inspired by my people, as I left Ishëm when I was small.”

The painter pauses and stops narrating; you must encourage him to speak. To keep the conversation going, we ask some questions about his childhood or youth memories.

– “Do you remember Lasgush Poradeci teaching at the Drawing School?”

– “Indeed, – he livens up and adds, but… these are names that are distant to me… I remember Odise Paskali, Abdurrahim Buza, and some others. In the Technical School, there was a classical branch and a ‘scientifique’ (scientific) branch. There I received my art education. Queen Mother Geraldine and the Prince approached me and housed me in the ‘Naim Frashëri’ dormitory. Near the dormitory, Odise Paskali set up the Drawing School as an evening school.

Kaceli, Zajmi, Grezda, etc., studied there. I would go after finishing my lessons, at night, in the evening hours from eight to ten. Odise Paskali, when he saw his name in my catalog in France, was pleased because he thought that if Kodra put my name as his first teacher, it means he has not forgotten Albania.

Buza was a good professor. I remember when I did a work ‘Café Durrësi’ in Tirana. It was a cafe for the wealthy. Rich people went there because inside the venue, Gypsy women performed dances. They danced while holding a ‘napolon’ (gold coin) on their forehead and they must not overturn it while dancing. If they didn’t overturn it, they won. Buza was on the commission and they liked the painting and gave me a reward.

The writer Haki Stërmilli published the book ‘If I Were a Boy’. Girls were secluded; they dealt with the house and family, while boys were understandably free. The book was addressed to the girls who were secluded, that they too should be free. I did the drawing for the cover, where I presented a girl enclosed within a window.

Haki Stërmilli worked across from ‘Lumo Skëndo’s’ bookstore, a large bookstore that had ‘Larousse’, fabrics, and many other things. It was a luxury shop. Albania lived well then. It was the Monarchy. Children were well-dressed. Girls stayed together. I remember Nermin Vlora, Vera Blloshmi… very beautiful girls. In the center was ‘Vllazën Kaceli’, who had a haberdashery and bookstore where we bought colored pencils and notebooks.

Upon finishing the Drawing School, I was waiting to receive a scholarship. Queen Geraldine had promised it to me and in the summer she calls me; ‘We will send you to Italy, for Fine Arts,’ – she said. While I was waiting for the scholarship to go to Italy, a journalist with the last name Shundi meets me. – ‘Ibrahim, the great Italian actress Maria Denis has come to Tirana with a group of tourists to be present at the screening of the film ‘Two Orphans’, in which she stars. Would it not be good to make a portrait of her in Albanian clothing’?

‘Of course,’ I replied. ‘Give me the photograph.’ The next day, the journalist had met the Italian actress at the ‘Kontinental’ hotel on ‘Mussolini’ Boulevard. I did the portrait and we went together to give it to her. She was with the Consul of Italy, Attoma Lorusso. She came. The girl was very beautiful, like Brigitte Bardot, very famous. – ‘How beautiful,’ she said when she saw the drawing, ‘it resembles me, I like it very much. You are very talented. Why don’t you come to Italy to study painting’?

Her words were of great importance. Two days later, the consul sent me a letter stating that I had been granted a scholarship to study in Italy. So I had two scholarships: one from the Royal House and the other from Italy.”

The painter took a breath and after taking a sip of water, he began to wait for another question. He is not in a hurry and remains still. He breathes with some difficulty.

– “When did you have your first exhibition?”

– “In Italy, they welcomed me very well, and the first work I did was for the ‘Sindacati’ (The Municipality). They invited me and gave me a reward of 250,000 lire of the time, as well as the first prize. ‘What is this prize?! Why are you giving it to me?’ – I asked. ‘We gave it to you – they told me – because Kodra proved to be the smartest, the best boy of Brera’.” (Laughs)

“After three years, before finishing my studies, the Italian state brought some of us students to Albania to see if the Italians were doing bad or good. We saw that they had built the Ministries, Hotel Dajti, they had started the railway, they had done many things; the Durrës marsh which brought fever and malaria, they had drained it. They said Albania is a very rich country, as is still said in Italy today, that Albania is the land that gave us the world’s bread and has not only petroleum, but – they don’t know it, but the engineers are saying it – great underground wealth.

They have sent, and the word is that they have sent 150 entrepreneurs who are working to elevate Albania from a tourism perspective, to make the country more beautiful, to become the tourist destination of Europe, of great importance.”

I remembered that Kodra’s last joint exhibition with former Albanian students who studied at the Academy of Rome was held in 1940 in Bari, and since then he had no longer exhibited with them.

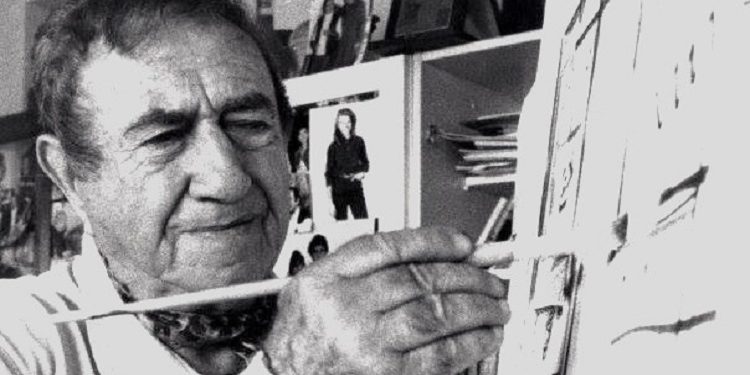

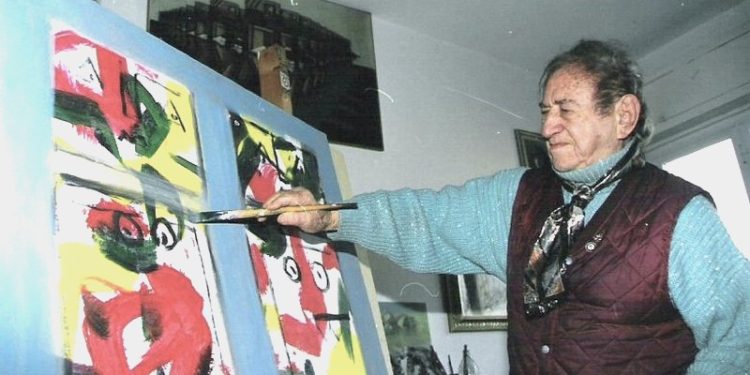

The painter added: “They remained, whereas I continued; I had interest. I signed contracts; I received ten million a month and 100 points. The point system is the French way of valuing painting. In Switzerland, I worked well and held exhibitions everywhere. I have 1,000 paintings there. I believe I have made more than 6,000 or 7,000 paintings worldwide.

The beginning in Italy was difficult, – Kodra continues, – but then word spread: ‘This Albanian painter is good!’ – here and there, and foreigners came from Paris and Germany. My agents held exhibitions everywhere, from Tokyo, Canada, London, Paris, etc. Everyone has written the most beautiful words about me. I keep them in the archive, which is a museum in my home – books, newspapers, magazines, numerous articles – but I believe they found the most beautiful words to develop my work.

In the early years, I did drawings from the war, which was always published. Meanwhile, the communists invited the great poet Paul Éluard. He was invited by Giancarlo Vigorelli, ‘un grande scrittore’ (a great writer). We formed a commission and he asked me to make a drawing for Paul Éluard. I did it, and he put it in his magazine ‘Mercurio’. Éluard wrote his last poem. He could not leave the house because there were those ‘guardia tedesca’ (German guards). It was the time of the ‘Maginot Line’. He entered the house and wrote this poem:

Que voulez – vous la porte était gardée

Que voulez – vous nous étions enfermés

Que voulez – vous la rue était barrée

Que voulez – vous la ville était mâtée

Que voulez – vous elle était affamée…”!

Kodra’s raspy voice echoed as the painter brought back the verses from the poem titled “Poetry and Truth,” with a passionate recitation in beautiful French, spreading through the quiet of the Tirana evening.

“Éluard, – Kodra continued, – accompanied by the writer Beniamino Joppolo and a journalist from the newspaper ‘L’Unità’, came to visit my studio. Seeing some works, the poet remarked: ‘Kodra is the primitive of a new civilization!’ The word got out and the newspaper published it. This saying has always been taken as a reproach… but in my painting, what are these figures with squares and geometric shapes?! I have always said, today it is your portrait, the portrait of all humanity; today we are in a civilization of consumption, meaning man has lost his sincerity.

We are closed off. I wrote it then, they liked it and the word spread; these figures I make have created a great space, they are liked… the civilization of consumption, of this political time today. This saying of Éluard’s has been taken up and developed by the greatest critics; they have found the most beautiful words to write about my painting. At that time, the artists Breton, Aragon, and Paul Éluard were very famous.”

– “How did you meet Picasso?”

– “In Milan, – Kodra replied, – we painters of the ‘Novecento’ stayed together: Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, Francesco Messina, a great sculptor, Carlo Riccardi, Achille Funi, the world’s greatest fresco artist. He taught frescoes. My friends were Ennio Morlotti, Cassinari, Gianni Dova, Roberto Crippa, and Renato Guttuso, who was a very close friend of mine.

Renato was linked to the Resistance. ‘Uno grande scrittore’ (A great writer) Davide Lajolo, a friend of mine, we had a mutual liking for each other, and in the evening we would all look to have dinner together.

They loved me. The poet Salvatore Quasimodo always stayed there because he had his house near Brera, ‘Via Garibaldi’ no. 16; I was his friend. He always came to see me. At ‘Biancheria’, which was across the street, the greatest in the world would come. It was very famous at that time. They called it the ‘Quartier Latin’ (Latin Quarter), where the greatest people came.

In 1948, Italy was in the hands of the communists, from a cultural perspective, because after the Resistance, it was programmed that Italy would become communist. Many fascist hierarchs transformed into communists and worked so that instead of the Peace Congress being held in Paris, it was held in Rome. Then art and the Resistance, instead of doing it in Paris, they did it in Bologna…

Guttuso introduced me to Picasso. He immediately became very good friends with me; he invited me four times to Cannes, to the Côte d’Azur; ‘Mon ami peintre Kodra!’ (My friend the painter Kodra) – Picasso would always say when he met me.” / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue