Part Two

Excerpts from the book: ‘ALIZOT EMIRI – The Man, the Library, and the Noble Soul’

A FEW WORDS AS AN INTRODUCTION

Continued from the previous issue…

Memorie.al / When we, Alizot’s children, would tell “Zotia’s” (Alizot’s) stories in joyful social settings, people would often ask us: “Have you written them down? No! What a pity, they will be lost… Who should do it?” And we felt more and more guilty. If it had to be done, we were the ones who had to do it. But could we write them?! “Not everyone who can read and write can write books,” Zotia used to say whenever he handled poorly written books. When we discussed this “obligation” – the Book – among ourselves, we naturally felt our inability to perform it. It wasn’t a job for us! By Zotia’s “yardstick,” we were incapable of writing this book.

Would Alizot, as a bookseller, have agreed to keep this book written by us in his private bookstore – for example, about a similar character? Certainly not! If he were forced to read it, he would have ended up staying in his Gjirokastra dialect: “Nonsense… mere trifles!” Then, who could write it for us? The goal was simple: A tribute to Alizot, as a distinguished bookseller, a well-known and beloved character in Gjirokastra in his time, but also as an extraordinary parent. We took courage.

We have some advantages: We are from Gjirokastra, and we were contemporaries of our father! Moreover, in many of Zotia’s pleasant incidents, we were witnesses or “victims.” But what about the literary value?! We will compensate for the literary poverty with a child’s love for their parent. Agreed! Besides, when it comes to writing, we aren’t at zero. After all, we passed through the classrooms of the “Asim Zeneli” high school, famous at the time, and furthermore, we were students of Agim Shehu, the talented poet and literature professor.

Wait… wait, we almost forgot, we are also Alizot’s children; surely he must have left something in us too. He did… he did, but he left something as a bookseller, not as a writer! Hesitation again! All these factors, which seemed generally positive, were not enough to take the courage to write a book.

We debated:

The reader doesn’t owe it to us to read our school-level essays. “Don’t worry about the reader; they are wise enough not to buy our book, no matter how confused they might be by the countless publications of authors who haven’t read a single book themselves but compensate with endless writing.” Aren’t we the ones who have said so often: “Oh Lord, intervene, for you have forgotten us again! Take the pen away from us! Don’t let us put our own eyes out!” To write it, or not to write it…?! We finally solved it. We will make a book for our family, for Alizot’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren. We won’t sell it in bookstores.

We will distribute it to Alizot’s friends and their families as a sign of gratitude for the love and respect they showed toward our father. They will forgive us for the lack of literary value. They know we are not writers. Zotia would have agreed with this approach. His soul would rest easier! We decided that Shpëtim would write it and Ibrahimi would complete it.

The Portrait of Alizot

To highlight Alizot’s portrait, we have completed this collection with biographical elements and assessments written by many authors in their books, such as Dalan Shapllo, Elmaz Puto, Bajo Topulli, Baftjar Dobi, Sevo Tarifa, and Vasil Dilo, which we have excerpted and placed here, along with Zotia’s humor. Our heartfelt gratitude goes to them!

Messrs. Vasil Kati, Skënder Çiço, Petro Dudi, etc., have also written kindly about Alizot in their books, to which we are also grateful. We respectfully thank the people of knowledge and letters: Dritëro Agolli, Muzafer Xhaxhiu, Nasho Jorgaqi, Gaqo Veshi (Hyskë Borobojka), Agim Shehu, Jorgo Bulo, Adem Harxhi, Thanas Dino, and Andon Lula, who welcomed the news that Alizot’s children were fulfilling a wish of theirs and of society to commemorate Alizot. With what love and respect they gave us their impressions of knowing Alizot!

We would like to emphasize the special contribution of Prof. Nasho Jorgaqi, who stayed with us from the moment we asked for his impressions. He praised us for this initiative, freed us from our insecurities, and encouraged us, constantly urging us not to delay the work we had started. He read the raw material we prepared and gave us the advice of an “old master” before we sent it for editing and publication.

Humorous Anecdotes

We were able to highlight only a very small part of Alizot’s humorous incidents – only those where we were present and some we happened to hear from the retellings of others. How true are the stories written in these bits of humor?

It must be understood that they were not written by the author himself, Zotia. It had never even crossed his mind that one day his witty sayings would be written down. His humor was natural. With humor, he challenged poverty and the stress of the times. He felt wealthier and calmer. He would have needed a secretary following him from morning till night to pick them out.

And a secretary he certainly did not want, even if they were assigned to him by force. He couldn’t afford it. It was a time when people talked to themselves out of numerous troubles and looked back to see if anyone had heard them. Imagine when you wanted to make a joke! Thus, these stories are brought from memory after about fifty years, as well as from oral traditions. They are not recordings!

We have taken care that their retelling is as close to reality as possible in essence, while in form, there may certainly be small changes, because Alizot himself never told the same story the same way twice. Except he had the gift of maintaining and even increasing the dose of humor. He made the story even more pleasant on the spot. He never bored you when he told a story.

We particularly wish that no one is hurt by these memories. It was in Alizot’s nature not to hurt others. He controlled his humor so that it was always as kind as possible. He wanted everyone to laugh. Except for those cases when he used humor to strike a vice. In case someone feels hurt, surely, we – the children – have hurt them unintentionally. For that, we apologize now!

Does anyone have anything to add? With what pleasure we would welcome it! But did we manage to bring Alizot’s portrait alive and in full? We do not feel at ease! We know well that we cannot lay our father’s “egg”! As long as we continue to introduce ourselves as the children of Alizot Emiri, it means we are not exactly like him. We would have to bring him down to reach him ourselves…! No! Impossible!

It would not be modesty at all to say that we “remained like oregano at the foot of an oak.” This is the only misfortune our father left us – that we will leave this world as children, “Alizot’s children,” but nonetheless, each of us will also have his own individuality and age.

With respect for the reader,

The Children of ALIZOT EMIRI

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

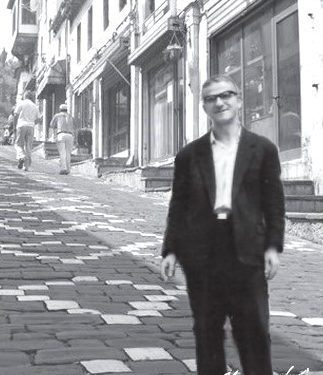

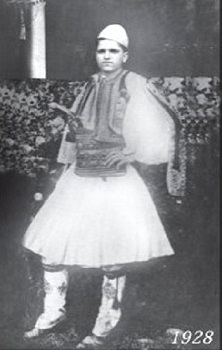

ALIZOT EMIRI was born in Gjirokastra on February 3, 1914, into an autochthonous Gjirokastra family. For economic reasons, he cut his schooling short and began working at a very young age. From 1928 to 1936, between the ages of 14 and 22, he worked in Gjirokastra at the Post Office, at the newspaper “Demokratia,” and as a seller of books and newspapers. In the period 1936-1938, for economic reasons, Alizot was forced to go to Kuçova and Tirana, where he worked as a switchboard operator and telegraphist.

In 1939, together with his brother, Mufit, who was a student at the Lyceum, they opened a rented bookstore in Gjirokastra named “Dante Alighieri” (later called “International Bookstore”), which operated until 1947-1958. During this period, they brought literature in Italian and French to the bookstore, because these languages were known by the intelligentsia who had studied in the West, as well as by the student youth who learned them at the Gjirokastra Lyceum.

They established connections with Italian publishing houses and book and newspaper distribution agencies, which periodically supplied the bookstore with literature requested by readers. They brought periodicals (newspapers and magazines), literary editions of world masterpieces, and encyclopedic publications such as “Larousse,” “Enciclopedia Italiana,” etc.

Later, they connected with E.S.I. (Edition Social International) of France, through which they ensured the arrival in Gjirokastra of progressive literature in French, such as “Cahier de la Jeunesse,” “Clarté,” etc. Through Uncle Braçe, their father, who worked at the post office, they managed to bypass the censorship control of packages containing prohibited literature coming from abroad.

In the bookstore-stationery shop, they also traded gramophone records produced by Italian record labels, where, in addition to the classical repertoire, they brought parts of the Albanian folk song repertoire sung by Tefta Tashko, as well as polyphonic songs recorded by Neço Muka.

The Emiri brothers’ bookstore became a true cultural center, especially for the student youth of Gjirokastra. In this bookstore, heated discussions of patriotic youth took place. With the occupation of Albania by fascist Italy, the Emiri brothers openly expressed their hatred and protest against that occupation. Mufit, an excellent third-year student at the University of Medicine in Padua, Italy, interrupted his studies to become active in the Anti-fascist Movement in Gjirokastra.

The Emiri brothers refused to join fascist organizations and refused to sell the fascist newspaper “Popolo d’Italia” in their bookstore. (For this reason, the Consul of Saranda closed their bookstore in Gjirokastra for six months). Despite this, the distribution of progressive literature did not stop. It was distributed illegally by Mufit to his friends with progressive ideas.

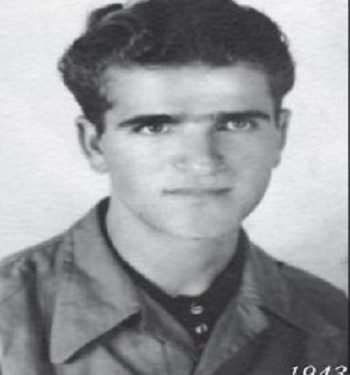

The Emiri brothers participated in anti-fascist protests and demonstrations, and their anti-fascist stance caught the attention of the occupiers. They were arrested as defeatists in March 1942, after the ceremony commemorating the war of Mashkullora, when the fascist carabinieri found a flag raised with the embroidered call: “Today in our hearts, tomorrow in the mountains of Albania!” Alizot was arrested in Gjirokastra, while Mufit was arrested in Tirana. They were held for two months in prison and were sentenced by the fascist military court to one year of conditional sentence each for subversive activities (against the occupation).

On October 4, 1943, Mufit was killed at the age of 23 by German forces and their collaborators, who fired mortars from the castle of Gjirokastra onto the population that was climbing to the upper neighborhoods for protection. Alizot actively supported the war against the occupiers, being a liaison for the First Operational Zone, and providing various financial or material aid, such as typewriters and writing paper.

After the war, in memory of his slain brother, Alizot several times provided aid to the city’s schools, with school supplies and items to help poor students. At the beginning of 1946, central government leaders, who knew Alizot’s special talent for trade, proposed that he start working in the state trade structures in Tirana, but first, he had to become a member of the Communist Party. Alizot did not accept this condition! He did not want to be included in party structures.

On July 22, 1947, Alizot was arrested, and after about five months of investigation, on December 10 of that year, he was sentenced by the military court of Gjirokastra. He was accused of agitation and propaganda against the people’s power, as well as participation in a traitorous organization for the violent overthrow of the government. Alizot was a citizen of broad horizons, a man of progressive ideas, of free thought, and for the free market. He was characterized by a spirit of protest against injustice, but never a man of violence.

Even behind bars, he opposed the injustice of the sentence. After this, by decision of the Presidium of the People’s Assembly, his sentence was reduced from 10 to 4 years. After his release from prison at the end of 1951, Alizot worked initially as a private radio technician, later as a seller in the state Trade enterprise, then opened a private haberdashery-stationery shop. After 1956, when private activities were banned, he worked as a librarian in Gjirokastra until he retired in 1973.

On November 12, 1983, he passed away from a serious illness, with his family in Gjirokastra. The people of Gjirokastra honored Alizot with an extraordinary participation in the funeral procession to the cemetery. In complete silence! Without a word! Without… “Unforgettable be the memory…!” The “class” struggle hung over Alizot’s head, “faithful,” even after his death. His remains rest in the city cemetery of Gjirokastra, that city where he spent his entire life and where he left a name! If we were to formulate a C.V. for Alizot, it would be as follows:

Education and Culture

He was educated as a self-taught man and cultured through the continuous reading of books, as well as the frequenting of cultural and artistic environments. Thus, he had the great school of life and books. He had beautiful and aesthetic handwriting, a unique calligraphy.

Professions

In conditions of extreme poverty, in a country with a very low level of development, born and raised in a poor family with no inherited wealth, Alizot strove for the survival of the family, starting everything almost from zero. He mastered and practiced several professions:

Mail distributor, seller of books and newspapers, switchboard operator, radio technician, photographer, haberdashery-stationery merchant, repairer of fountain pens and lighters, artisan producing envelopes and boxes, but above all “BOOKSELLER.” In the multitude of professions practiced by Alizot, one reads his special effort to face life with dignity in those difficult conditions.

Foreign Languages

He mastered the Italian language at a very good level. In Italian, Alizot had read the masterpieces of Italian and world literature which were not translated into Albanian. He knew at a communication level French, Greek, and German. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue

![“When the party secretary told me: ‘Why are you going to the city? Your comrades are harvesting wheat in the [voluntary] action, where the Party and Comrade Enver call them, while you wander about; they are fighting in Vietnam,’ I…”/ Reflections of the writer from Vlora.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)