By Rezarta Delisula

Part One

Memorie.al / Eighteen years is a long time – endless – as you wander from one horrific prison to another, from Burrel to Spaç; once to see a husband who has lost half his body weight, and next, a son imprisoned at a very young age. They are endless when you struggle to obtain travel permits to move from one city to another within Albania, as you suffer in horrific internment camps, leaving your books behind to tend goats in the shack where you live, hoping for a single glass of milk; eating sweets made with the blood of a freshly slaughtered pig, convincing young granddaughters that their father is not an “enemy,” and carrying the burden of the pain caused by the absurd, loathing stares of others on your back…!

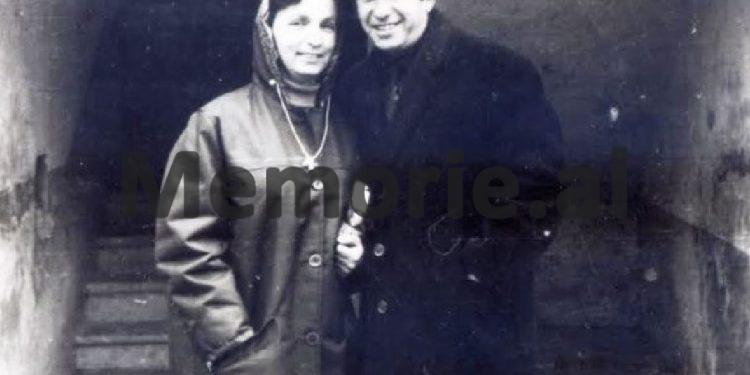

This was the fate of Liri Lubonja, the wife of the former director of Albanian Radio-Television (RTSH), Todi Lubonja, for 18 consecutive years, from 1974 to 1991. In her written memoirs, “Far and Among People” (Larg dhe mes njerëzve), we touch upon the drama of an entire family, and through Liri, the drama of many other Albanian families as well. It all began after the 11th Festival at Albanian Radio-Television.

The liberalization of music and lyrics, European attire, and the imitation of foreign singers by our own were some of the accusations thrown after the 11th Festival at RTSH. This year, the categorization of “enemy groups” reached the people of art and culture. Immediately after the 11th Festival, at the meeting of the Presidium of the People’s Assembly on January 9, 1973, Enver Hoxha delivered a speech where not only was the festival criticized, but direct responsibility was placed on the shoulders of the Director of RTSH, Todi Lubonja.

Liri Lubonja’s Memoirs: The Starting Point

“The comments from that speech created an atmosphere of danger and anxiety that Todi and I began to feel more and more. In the evenings, when we went out for our usual walks, thinking that Todi – as the person directly criticized for the festival – should have some information, friends and concerned acquaintances would stop us in the street, wanting to know any details. One of the most troubling questions was: ‘How far will this go?’ No one knew, least of all us,” Liri Lubonja writes in her book. At RTSH, consecutive meetings regarding the 11th Festival began, and in the February plenum, Enver Hoxha warned of a special plenum where ideological issues would be examined.

Everywhere, people talked about the 11th Festival. The youth could not understand the “evil” in the lyrics, music, and clothing that were allowed to appear on television. Around Todi Lubonja and his family, everything was becoming more difficult. “Meanwhile, I continued to work every day in the scientific hall of the National Library, where many employees of the Institute of History also came. I always sat at a table that was leaned against the wall. One day I noticed that the table next to mine began to stay empty. The woman who usually sat there worked in the mass organizations, in a position of responsibility. I saw that she had moved to the other side of the hall,” Liri Lubonja recalls.

The Bill

At the end of March, Hysni Kapo, after speaking to Todi Lubonja about the great damage he had caused the Party, communicated his relocation to Lezha, where he would go as the director of the Construction Enterprise. On April 15, Todi began work, while Liri, who worked at the Institute, was ordered by Hysni Kapo to quickly complete the formalities and leave her job for Lezha, where she had been assigned as a history teacher at the “Hydajet Lezha” general high school.

Following a character reference prepared with kindness by Muhin Çami – where, amidst the discussions, the long hair of her eldest son, Fatos Lubonja (a fourth-year student and married), also found a place – on April 30, 1973, Liri Lubonja departed for Lezha along with her younger son, Gimi, who was a high school student at the time.

Liri was assigned to teach the first three years and only one graduating class. “The only pleasure this undeclared internment gave us were the walks we took in the evenings on the road leading to the Island of Lezha. We were convinced, without anyone telling us, that our house had been ‘equipped’ with wiretaps; but when Fatos came one Saturday, he brought us a warning from a childhood friend, an employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, who had told him: ‘Tell them to be careful, they have planted microphones’,” says Liri Lubonja. She adds that the atmosphere in their home was stifling, like a kind of absurd theater where the actors were themselves.

Meanwhile, Gimi attended high school and was one of the best students in his class. He was active in both sports and playing the guitar, but he was never allowed to take the stage because he was Todi Lubonja’s son, and the First Secretary of the Party Committee in Lezha could not permit it. The 4th Party Plenum, to be held on June 26, was the big test Todi Lubonja had to pass. He had been asked to perform a strong “self-criticism.”

“On June 27, after I finished teaching, I rushed home, worried. Had Todi returned? What had happened? How far had they gone? Gimi opened the gate for me. He looked sharp, holding a coffee pot (xhezve) in his hand. Todi had just returned. In a low voice and with few words, Gimi told me what had happened and rushed to make him a coffee.

Todi was upset, but more so disgusted by the arrogance, the banality reaching the level of street thuggery, the slanders, and the servility of many of those who had been ‘comrades-in-arms’ – members of the highest forum leading the country: the Central Committee of the PPSH. He mentioned names and told me what they had said. I knew many of them, and for some, I was not surprised they had behaved that way. The next day, in a mock meeting where the collective of the construction enterprise had gathered, Todi’s dismissal as director was announced with great fanfare,” Liri Lubonja recalls with pain.

According to her, besides the accusations coming from Tirana, fresh ones from Lezha were added, such as “he associated with kulaks,” which had been said by Drania, the secretary of the organization. A few days later in Lezha, a broad meeting with the city’s intellectuals and officials was organized, while the envoy from the Central Committee denounced the “enemy activity” of Fadil Paçrami and Todi Lubonja. Naturally, after this meeting, the consequences would also fall upon his wife, Liri, who was part of the basic education organization. People began to distance themselves from her.

Divorce?

Even though Liri Lubonja had been working as a high school teacher for several months, her character reference had not yet been read by the organization. After Enver Hoxha’s report held at the 4th Plenum, a meeting of the organization was scheduled. “One of the communists from the organization – the one from the eight-year school – came to see me. Her son was Gimi’s classmate. She advised me to divorce Todi. She told me I had to do it for the sake of the boys. I refused her and told her that even the boys thought like me. I had truly spoken with Fatos and told him that they would surely ask such a thing of me, and that I had no intention of doing it,” says Liri Lubonja. In truth, at the meeting, she was openly asked to divorce her husband, Todi, which she did not accept. In that early July of 1973, she was expelled from the party, where she had been a member since 1944. Naturally, her dismissal as a teacher followed immediately.

Liri was assigned as a warehouse worker in the pastry workshop – a very difficult job, considering that all the warehouse workers before her had ended up with financial deficits, and one had even been sentenced to 10 years in prison for it. There was no other choice; she had to accept the job. Todi, at that time, earned only 400 lek as a “normist” (production worker).

The difficulty was apparent from the start. At the end of the month, she was found to be short one hundred byreks, and later the deficit increased to 100 pieces a day, which she had to pay for out of her salary. After several tribulations, Liri requested to leave the job, and finally, she was assigned as a worker in the agricultural warehouse, a job she started on October 12, 1973.

“Those outbursts of Enver Hoxha had not ended. They removed Todi as a normist because he did not have the ‘appropriate professional training.’ From then on, he would have to produce eight square meters of tiles a day to earn four hundred lek – a job that required muscle and physical strength,” says Liri, recalling with pain that her husband’s health – then 51 years old – was deteriorating.

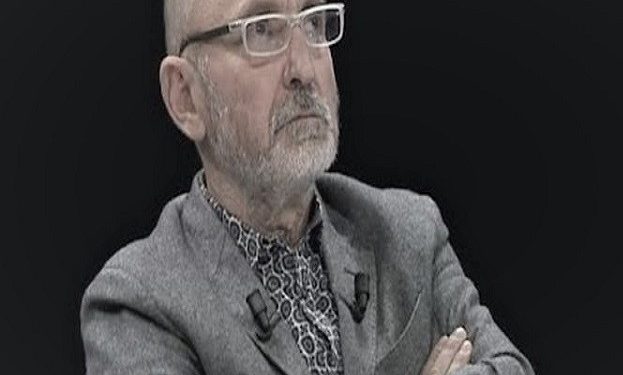

At that time, Fatos and Zana were in their final year of university and had their first child, Ana. On January 2, 1974, after celebrating the New Year, they took their last photos together, because for two consecutive decades, the hell of prisons and internment began. After finishing university, Fatos and Zana were assigned to Burrel. The couple was expecting their second child. Zana stayed in Lezha, while Fatos departed for Karpen in Kavaja, where the military training for the Faculty of Natural Sciences was being held. On June 27, Fatos and Zana’s second daughter was born, whom they named Tetis, after the goddess of the sea.

The Arrests

On July 25, at 6 o’clock in the morning, employees from the Department of Internal Affairs knocked on Todi Lubonja’s door. They were looking for Fatos. “I was shaken. For Todi – though it seemed absurd and I didn’t want to accept it – I had prepared myself spiritually even for prison, even back in Tirana; but it never crossed my mind that they would lay a hand on the boys as well. This I could not endure. Fatos in prison!” writes Liri Lubonja. Two days later, on July 27, the head of the Department, Mithat Bare, declared the arrest of Todi Lubonja. A diabetic for years, they did not even allow him to take his medicines, calling them a “luxury.” “During the interrogation, they told Todi: ‘We have arrested Liri too.’

A heavy psychological pressure, a blow against the detainee, who during interrogation is completely isolated, without any connection to the family. Todi told me how, when they took him out of the cell, he would secretly glance at the shoes, sandals, and women’s slippers lined up in the corridor, trying to find mine among them,” she says sadly, recalling that her husband was taken from the house in a thin suit, in which he spent the entire winter in the cell.

After the raid on the house, and not even 13 days after Todi’s arrest, the Central Commission for Deportation and Internment decided that Liri Lubonja and her son Gimi, who had just finished high school, could not move from Lezha without travel permits issued by the Department of Internal Affairs.

“We hadn’t even known that a Commission for Deportation and Internment existed, but immediately we saw what that administrative sentence given to us meant: we were deprived of any possibility to go to the Investigator’s Office in Tirana to send food to Todi and Fatos according to the regulations. It was good that Zana was free,” Liri Lubonja writes in her memoirs about the horrific years. They often gave them the run-around for travel permits to go to Tirana, and once when they were supposed to meet Fatos, they lied to Liri and Zana. This later began to happen often. Even at the trial where Fatos would appear as the accused, his mother was not allowed to go.

On December 17, from a telegram sent by her daughter-in-law, she learned that he had been sentenced to 7 years in prison for “agitation and propaganda.” On December 26, the deputy head of the Department informed them that they had to vacate that house and move to the hospital neighborhood, up on the hill. Zana, with her two young daughters, joined Liri and Gimi. In those same days, Gimi, the youngest, received his call for military service.

There was no news from Todi, and likewise from Fatos, who had already been sentenced. Only in the second half of March did a letter from Fatos arrive. He had been imprisoned in Spaç. After his letter, they learned that Todi had also been sentenced. “I am very well, in unit 321 Burrel, come for a visit. Love, Todi.” This was the first letter the family received in March 1975, since his arrest.

The First Visit

Obtaining a travel permit for Spaç was not easy for Liri Lubonja. She had not seen her son for months; however, no one from the Department of Internal Affairs showed any mercy. After many requests and rejections, in April, she was able to secure the permit. The pilgrimage to Spaç was difficult. Liri relates that they traveled by bus as far as the Mat Bridge, then by chance vehicles, and for the most part, through the mountains on foot. “Pain and misfortune usually created a numbing contraction in me. A kind of sense of shame, a restraint against ‘weakness,’ made me experience the hardships within myself. In this, I resembled my mother, whom – despite the great pain and misfortunes she had in life – I had never seen with tears in her eyes.

However, when Fatos appeared before me, with his head shaved and wearing those hideous prison clothes, I was overcome with emotion and was on the verge of bursting into tears, had he not cautioned me two or three times as he hugged me tightly: ‘Don’t, it’s a shame.’ It felt like I was seeing a bad dream,” the mother recalls. That same month, Liri Lubonja was able to get a permit to meet Todi. After all the food was thoroughly inspected – all the eggs were broken, the fruit and byrek were cut into pieces in search of any “secret” letter – they let her pass. “Todi and I met in a small room at the entrance of the prison. We embraced with love and emotion, but with restraint”…, writes Liri Lubonja, who at the end of the meeting promised her husband that she would bring the granddaughters to visit…!

“How we experienced Enver’s death in internment”?!

Immediately after the sentencing of Todi and Fatos Lubonja, the unimaginable began for their family. Liri Lubonja, from the Institute of History where she worked before 1973, now had to endure loading and unloading at the agricultural enterprise, and not only that, but also cleaning the toilets (WCs). And after the heavy physical labor, the Lubonja family would experience all the internment camps in turn…! Through Liri Lubonja’s narrations in the book “Far and Among People”, we touch upon the real life of the internees, described by one of them.

Toilet Cleaner in the “Bachelors’ House”

In May 1975, Liri Lubonja received a document informing her of her dismissal from the agricultural warehouse and appointing her as a loading-unloading worker in the packaging warehouse; the salary was 370 lek. Suffering from hypertension and a collection of illnesses, she tried to request retirement, but this was certainly not accepted.

Her husband and son were in prison, so she had to work in places she had never imagined. The next job after that was in construction, preparing mortar and concrete, and later digging trenches. After appearing before the medical commission, the doctors forbade her from working in the sun due to hypertension, but Liri needed a job, so she had to look for one.

“They assigned me as a cleaner. My first task was cleaning the WCs, the stench of which poisoned the whole area. Without any hesitation, I entered those WCs. It wasn’t a matter of spite. Could you act otherwise when you were forced to spend most of the workday there? From someone completely foreign to them, I received a compliment: ‘She has turned those filth-holes into clean rooms.’ Good enough. They couldn’t give me a medal.

I continued to clean the WCs, to set the cauldron outside and wash the sheets of the construction bachelors’ house in those cold December days, when they gave me an envelope with a letter signed by the director. In it was written the termination of the job position,” Liri Lubonja recalls with pain. And after her work as a WC cleaner, she was assigned to gather sage (sherbelë). Because she was allergic to pollen, she had to take an allergy test, and based on it, she could not work there. Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue