Can One Remain the Same After Experiencing True Art?

By Minella Aleksi

Memorie.al / “I grew up with Kadare’s literature,” are a phrase commonly heard from many Albanians. I have asked myself: what does it mean to grow up or be formed by the literature of one of the world’s most important writers? Does it make you better, or not?

The Albanian society of the dictatorship years was filled with gloom, sadness, abundant proletarian revolutionary fervor, class upheavals, profound loneliness, but also much “revolutionary solidarity,” based on the principle of one for all and all for one. Anger thrived naturally in an atmosphere where success was sought through class struggle – a terrain of jealousy, envy, and other human vices.

During my high school years, I experienced the friendship of a family acquaintance who had studied humanities in Rome from 1940–’43 and kept a rich library of French and Italian literature at home. He showed me a book that had a note on the first page: “You are no longer the same after experiencing true art.” Every time I recall it, I ask: does it truly happen that way? Could Albanian society be saved by the experience of true art, or by what we call “culture”?

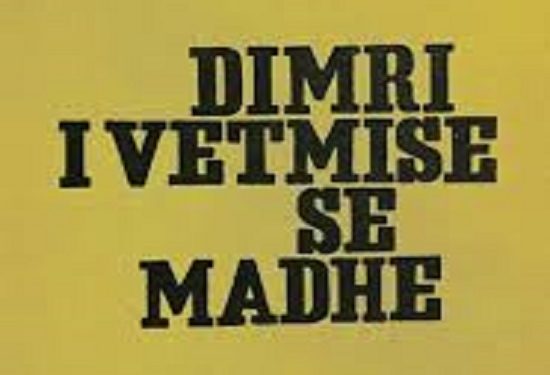

The Shock of “The Winter of Great Solitude”

When the novel The Winter of Great Solitude was published, it was the era of “working-class control groups” and the perceived danger of the “fattening of the revolution”; hence, the struggle against bureaucracy was required. An atmosphere of immense pressure and accompanying psychological anxiety prevailed. “Old pharmacists noted an increase in the sale of Valium.” Until then, no other novel or artwork had sparked such a comprehensive discussion. The writer was summoned to various worker collectives and the Writers’ Union; the debates were, of course, among the harshest. It was read more than anything before, but the most zealous in the discussions were often those who had not read the novel at all.

Many citizens found themselves as characters within the novel. It did not provide messages; the truths – the facts – were staggering. I will bring only one: The writer says: “Besnik thought about the struggle between the capable and the incapable, one of the most vicious wars within socialism. The trouble is that in this war, those who tire first are the capable,” he said to himself (p. 452). It was a time when the capable behaved with humility toward the incapable. Murderous communist indoctrination was violently expressed in the slogan “the voice of the masses.” The crowd was incited against the individual. This truth stated so brutally, had never before been cast into the field of social thought.

This staggering novel accelerated a visceral awakening. For a long time, anecdotes or humorous episodes began to circulate, reflecting different interpretations of the text. Precisely what Marcel Proust emphasized was happening: “While reading, every reader is, in fact, a reader of himself. The writer’s artwork is simply a kind of optical instrument offered to the reader so that the reader may discern what, without this book, he might never have seen in himself.” The Albanian community was divided: for and against the writer Kadare.

Reading Deeply vs. Reading Broadly

The novel opened a window for the communication of thoughts and awakened critical thinking. Later, I perceived this tectonic shift in Albanian thought as the shock a lung experiences when, after long exposure to smog, it finally receives pure oxygen. Naturally, I spoke with the family acquaintance who had studied in Rome.

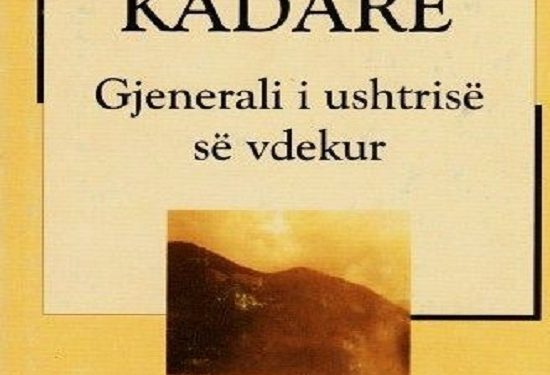

When I told him that previous novels hadn’t “moved” me like winter, he replied: “It’s not your fault; until now you have read The Liberators, The Swamp, and The Dead River – which you even have for your graduation exams. They haven’t yet included The General of the Dead Army in the exam theses! Until now, you have been reading ‘broadly’.”

“What does that mean?” I asked. After a pause, he continued: “Our professor of classical literature in Rome used to repeat: why read broadly when you can read deeply? With winter, you have begun to read deeply; it has awakened you, taken you by the hand, and opened the great door of a magnificent giant building. Amazed, as you walk through the vast corridors, you open one door after another, marveling at the mystical objects of the ancient past and beginning to explore them.”

It was the moment I felt my “Individual Self” within me. I felt as though I had emerged from a fog. Until then, I had walked inside the mist, as a “something” alongside many other “somethings.” With the “Individual Self” crystallized through the novel, I began to understand the meaning of critical thinking; with the mind’s eye, I was seeing what we call the “self.” I was distinguishing that small voice inside my head telling me that now you exist as a distinct being. I realized first that the “I” (the Self) is responsible for making decisions regarding actions to be taken. It is the engine that moves things inside my head in a wonderful, stealthy manner, in total darkness, hidden from my sight.

Above all, my “Self” suffers. It does not wish to be seen by me; it hates being seen and hides. The second thing it does is produce masterful justifications for its ugly actions. Everything my ego does is ugly. It knows no beauty, love, relaxation, or pleasure – only judgment, hatred, jealousy, tension, and dissatisfaction. It likes revenge. The ego always gives me exceptionally convincing arguments that every ugly thing I do is not my fault, but someone else’s.

Reading and re-reading these fictional novels empowered the sharpness of my mind to discover two antidotes: first, to detect where the ego usually hides from my observation, and second, to discover that in most cases, the fault was mine and not someone else’s. These discoveries freed me from the anxieties of the “Self”; I understood my identity. They sharpened my critical judgment toward myself to resolve the daily conflict between me and my “Self.”

The Ancient and the Modern

In winter, Ismail often makes complex references to Greek and Latin tragedians, Beethoven’s symphonies, etc. After winter, I naturally began to read The General of the Dead Army. It was a time when the cultural atmosphere was permeated by socialist realism. Yet, in that novel, neither the party nor revolutionary slogans were mentioned. Unlike the atmosphere of the “communist sun” and “socialist blue sky,” the events unfold under a sky full of clouds and rain that rarely stops. The novel was considered outside the norms of socialist realism and was criticized by official critics.

However, in the minds of readers, the novel was an alternative to the official one; the idea of rediscovering the humanist code prevailed. It brought to mind the humanist spirit of the European Renaissance. The disinterment of war victims reminded humanity of the universal lesson that nothing is more precious than peace. I experienced the emotions of true art. It felt as if my mind had expanded. I was viewing war and its consequences through the lens of the novel. Just as with winter, those Albanians who understood the novel’s significance were no longer the same.

The Real Estate of Human Culture

Later, much later, I learned from the writer himself that his genius mind had chosen, early on, to read not broadly, but very deeply. That is why he emphasized that “in the Soviet Union, I learned how I should not write.” Broken April, Chronicle in Stone, The File on H., The Palace of Dreams, and others followed as a necklace of world values.

In every Kadare novel, references to ancient Greek and Roman authors were omnipresent. Some Albanians who came into contact with great literature realized something crucial: modern literature often reorganizes old humanist ideas, whereas ancient Greco-Roman literature continues to suggest and invigorate new ideas. Long ago, I came across an album showing a stone in the courtyard of the Temple of Apollo in Greece, engraved with the words: “Know Thyself.”

In The Monster and The Ghost Rider (Doruntine), the writer touched the roots of Western civilization – the emancipatory foundations of human society. It was a time when the communist state had led us into the steppes of Siberia and far-off Asia, as far as possible from the Western civilization centered on man. The subject of literature is man; reading it helps us know ourselves.

The distant past of Greek and Roman antiquity returned to the modern table through another gate. Those who read and understood the novels felt once again that reading literature remains the surest way to live the life that the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates declared the only one worth living: “The Examined Life.”

I have reason to ask: what about those who have not read Kadare but make insulting him their life’s purpose? Or those who read him without understanding? Have they ever asked themselves what kind of person they are, or have they ever examined their lived lives? Can they detect the “Self” hidden in their souls, or are they trapped in the conflict of the narcissistic ego?

Final Reflections

The inability of a person to know themselves or examine their life led a wise man to say that the rate at which a person matures is directly proportional to the amount of shamelessness they tolerate in themselves. I doubt they have ever felt the “Individual Self” within. They continue to be fog, walking as fog among other things within it, indistinguishable from one another. It is said that the fog of the crowds shrinks individuality, while individuality liberates the intellect.

The writer spoke of these things at a time when the dictatorial regime dreamed of creating the “New Man.” That is why he brought us Aeschylus, This Great Loser. He leaves you breathless when he asks about a staggering truth: “How was the disappearance of ancient tragedies possible?” Strong ancient literature competed with the Bible, which religion had declared the “book of the world.” Yet, before the genius word of the ancient Greeks, the Bible was but an ordinary book – just as Jesus Christ was before thunderous ancient heroes like Prometheus.

Through Kadare’s work, the “collateral” of Albanian culture has gained a form of real estate – an enduring asset – of value to all of humanity. A classic is a work that gives pleasure to the minority that is intensely and permanently interested in literature. It survives because that minority, eager to renew the sensation of pleasure, is eternally curious and engaged in a perpetual process of rediscovery.

A classic is such because it has stood the proverbial test of time, and to do so, it has said something profound about life that helps us understand fundamental truths about people and our world. The writer Ismail Kadare did this as few in the world have. Therefore, Albania and Albanians are no longer the same./Memorie.al