By Çelo Hoxha

Part Two

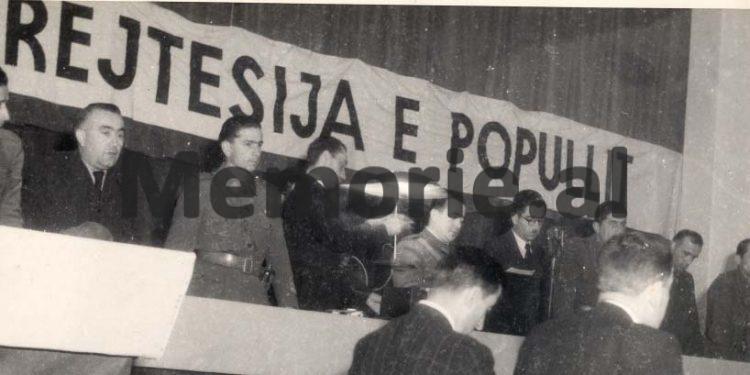

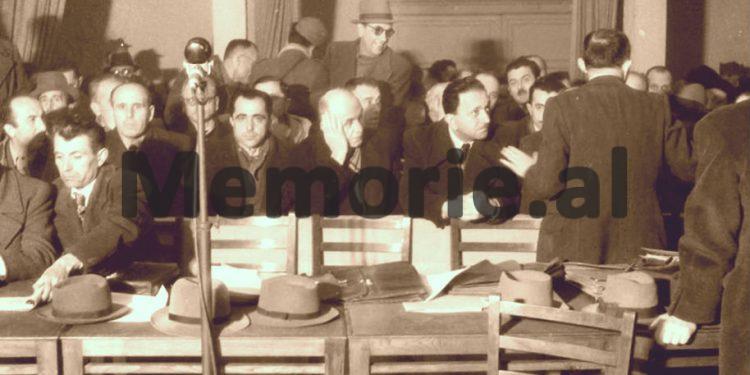

Memorie.al / In March 1945, a Yugoslav theatrical troupe arrived in Albania with a drama titled “The Occupation.” It was sent to perform in various districts – such as Elbasan, Korça, etc. – but not in the capital. The “Kosova” Cinema, the only venue in Tirana with a stage suitable for theater, was occupied. What was being staged there was not a drama, but a true tragedy, at the end of which 17 people were executed and 39 others ended up with long prison sentences. For the regime, the Trial was a festival of public lynching of 60 innocent people, most of whom were personalities with beneficial contributions to the history of Albania.

Continued from the previous issue

The only qualification required for investigators was that they “enjoyed the trust of the people.” This was an unverifiable, undefinable, and unmeasurable quality. Logically, it can be said that people appointed by someone who did not belong to the people could not enjoy the trust of the people, as long as they were not its elected representatives. The consent of the people could only be obtained in one way, and that was through voting.

A circular was sent to local units defining war criminals in 11 points. This definition constitutes the basis of two articles of Law 41 (14, 15), regarding war criminals and enemies of the people.

The best guide for uncovering crimes, according to the circular, would also be “the general opinion of the people.” More clearly: rumors. In cases where it was not possible to “obtain factual evidence, the depositions of several honest persons will suffice to make the charges believable [not to prove them] against the defendants.”

Another way to “discover” crimes was the interrogation of defendants regarding specific individuals and their subsequent arrest based on these depositions. According to the circular, valuable information could be provided by persons who had worked in offices as translators, secretaries, etc.

The Commission summoned as witnesses the residents of villages where killings had occurred during the war as the primary source for proving crimes. However, according to a circular dated December 27, 1944, it was not necessary for the persons testifying to have seen the facts they reported with their own eyes. It was sufficient for them to have heard these crimes being spoken of by the people.

On the other hand, this circular emphasized: “Testimonies issued by various persons regarding the good behavior of the arrested traitors are not only disregarded, but to curb these maneuvers and for the sake of justice, measures shall be taken against any person who in the future signs their name to exonerate the criminalities that have caused misery in our country.” Thus, the crimes had been committed, the guilty had been determined, and the investigative commissions were left only to find people to “testify” to the connection of the guilty to the crime!

Justice, regardless of how many times it may be mentioned in documents, had no connection at all to the “Special Court” and all the military trials against the so-called “war criminals and enemies of the people.” This was clearly articulated by the Minister of Justice of the time and Chairman of the Central Commission for War Crimes and Criminals, Manol Konomi: “Their judicial process will be of importance to our National Liberation War. And it will be a great political feat,” he wrote in the circular of December 22.

The Special Court and the Nuremberg Trials

The country responsible for World War II was Germany. The main authors of the war crimes it committed were sentenced in the Nuremberg Trials (November 1945 – October 1946). This trial judged 24 people: one was declared mentally unfit to be tried, one committed suicide before the sentence was handed down, 12 were sentenced to death, one in absentia, and the others were sentenced to various prison terms.

In contrast, the Albanian Special Court tried 60 people, sentenced 17 to death, 39 to various prison terms, and 2 to probation. Nuremberg acquitted 3 of the accused; the “Special Court” acquitted 2. According to statistics, Albania, which was a victim in World War II, turns out to have had more war criminals than Nazi Germany.

For the organization of special trials, the legitimacy of their organizers is of great importance. The Nuremberg Trials were organized by the legitimate governments of the Allies (with the exception of the Soviet Union, whose government was held by force by the communists since 1917, but was, nonetheless, internationally recognized). The “Special Court” in Tirana was organized by a government that came to power through force, via a civil war. And the Trial, according to the Minister of Justice, was a continuation of this war.

Another fundamental difference between the two trials was the composition of the prosecution and the judiciary. The prosecutors of the Nuremberg trial were the highest-ranking figures of the prosecution in the participating countries: The Soviet Union participated with the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, the United States was represented by a member of the Supreme Court, Great Britain was represented by the Attorney General, and France by the Minister of Justice, who later became the Prosecutor General of France.

The court also consisted of experienced judges from their countries of origin. The President of the Trial was a British judge, a member of the Court of Appeal for England and Wales (his deputy from Great Britain was a member of the High Court of England and Wales). The United States was represented by a former Attorney General and a candidate for the US Supreme Court.

The prosecution in the “Special Court” was represented by one person, Bedri Spahiu, without the most minimal legal training. He was a former military man who lacked university qualifications even for that profession. Meanwhile, the Court, consisting of 9 members, had only judges. The Chairman of the Court was Koçi Xoxe, with a primary education and a tinsmith by profession. In the group of the accused, there were more jurists – 7 in total: 5 graduated in Italy, 1 in France, and 1 in Yugoslavia.

In the judgment of the Nuremberg Trial, it is stated: “A large part of the evidence presented to the Court by the Prosecution consisted of documents and testimonies captured by the allied armies in the headquarters of the German Army, in government buildings, and other places… In this way, the charges against the defendants are based to the greatest extent on documents prepared by themselves, the authenticity of which is not disputed…” Meanwhile, the Special Court of Tirana, as mentioned above, relied on the oral testimonies of communist henchmen.

The Real War Criminals

Inside the “Kosova” Cinema, while the “Special Court” was taking place, there were indeed war criminals whose crimes were easy to prove, but they were part of the prosecution and the court. Documents testifying to their crimes are found in the Central State Archive (AQSH).

Bedri Spahiu, the prosecutor, is responsible for many crimes committed by the regional committee of the Albanian Communist Party in Gjirokastra, of which he was a member. In a report for the Provisional Central Committee, the Gjirokastra communists admit to having killed 11 people, 10 of them Albanians, including the sub-prefect of Kurvelesh, Novruz Taçi, with the aim of “dominating the region.” Most cynically, while Terenc Toçi was in prison and Bedri Spahiu sentenced him to death, Spahiu’s relatives had occupied Toçi’s house!

Koçi Xoxe, as a member of the Central Committee and the National Liberation Council (KANÇ), is responsible for a number of crimes. On November 11, 1943, he signed a circular informing of the murder of Zef Ndoja by decision of the Central Committee. He was aware of, if not ordered, the killing of 6 “Ballists” in Devoll.

Hysni Kapo, a member of the Special Court, could have been convicted as a war criminal for a series of easily verifiable crimes, such as the execution of two gendarmerie in Shpat, the execution of partisan Imer Romësi as a deserter, the looting of property in Balbardh, and the burning of the village of Sinë in Dibra, etc.

Beqir Balluku, another member of the Special Court, as commander of the Second Brigade, could have been convicted as a war criminal for the looting of property belonging to the Skënderi family in Frashër; for the burning of houses and looting of property of Izet Hysniu, Sabri Nuredini, and Qazim Goblara. All these crimes were carried out by order of the General Staff and implicate those who gave the orders.

Conclusions

The “Special Court” was a continuation of the civil war in another form. Essentially, it was an instrument in the hands of the communists for the physical liquidation of political opponents. Designing the “Special Court” as a “great political feat,” as the Minister of Justice Manol Konomi called it – which executed 17 people and punished 41 others with long prison terms -automatically classifies it as an act of terrorism. This is terrorism: the use of violence to achieve political goals./Memorie.al