Memorie.al/ “The feet whose stride was halted.” This is the phrase that comes to mind when I see the internment-deportation memorial in Lushnje. Atop thin calves (of malnourished bodies), an imposing concrete structure stands. Black, heavy, hard, and tightening. Like communism. Suffocating and restrictive. Like communism. Distorting, just like it. Beneath it – small, white, powerless, and halted – the feet of people struggling. There are no names for them; they belong to everyone, to all those who, at different times, were brought to be isolated in the nearby villages. The symbolism is clear, and the black-and-white two-tone is broken only by the flowers left in memory of souls who never got to intoxicate themselves with their fragrance.

LIVES HANGING BY A THREAD

“At the end of November 1953, the infamous Tepelena camp was closed. Those who were released from internment crossed the barbed wire and took the road home on foot. Thousands of other internees from the camp were loaded onto Ministry of Internal Affairs trucks and set off toward the unknown…! The center of internment was Savra, a village on the edge of the road in Lushnje, where the command was also located.”

Gentiana Sula, chair of the Authority for Information on Former State Security Files, begins her speech this way regarding the Lushnje camps, as part of the activity “Dignity in the Face of Totalitarianism,” held on Sunday at the city’s cultural palace.

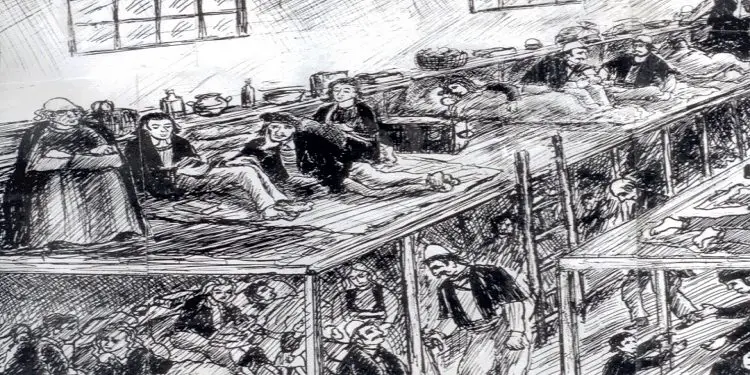

Present were former internees and their descendants, as if to mark the triumph over death and oppression, now that in freedom, many of them have moved far away. Alongside the files placed on a table – which constitute the archival exhibition of State Security persecution in the internment villages of Myzeqe – images of the camp internees hang in the air of the hall: children, adults, families, weddings, the elderly, pickaxes, shovels, fields being worked, emaciated women, pale faces, and frail workers. They look like dolls, all so thin as if they might break at any moment. Their hanging images show all the processes of life in the camps, from birth to pain. The hanging photographs sway when the open door of the hall in a still-poor city brings in drafts of air.

But every time they sway before my eyes, I think about how, like those photos, the lives of those people hung by a thread. But not symbolically. Not everyone made it out of the camps alive. The swaying of the photos in the wind only makes you imagine what earthquakes shook their lives in the camps. Likely, the exhibition workgroup, led by Ardita Repishti, had “lives hanging by a thread” in mind when choosing this display method, where life and death, weddings and joy, fear and pain, kiss and meet in the dry air of this August.

Young people laughing, united families, children growing up near grandmothers, young couples starting a life amidst ruins – for a moment, life seems entirely normal. Until the inscription becomes visible: The Camp of… They were merely barracks, and the smiles frozen in time were but an attempt to live, momentarily setting aside the people they had lost before that moment was captured. Fathers who escaped, children who never knew their parents, divided families, fear for tomorrow, and hands clenched in paranoia for what might come.

THE CAMPS OF THE “ELITE”!

Having arrived from the Tepelena camp, as soon as they descended into the marshy area of Myzeqe – which later functioned as the “29 Nëntori” state farm – even outside the barbed wire, they were again lined up for the next roll call at the sound of the çanga (iron bell).

Genta Sula notes in her speech that “enemy of the people” families from all over Albania were settled in 7 barracks under very difficult conditions, and for them, a new life began, marked by farm labor, daily roll calls, and adaptation to new living conditions. “Conceived as a center for political internment where ‘overthrown classes’ would be kept under control, Savra transcended the reasons for which it was created.”

“In just a few years, Savra witnessed the first marriages between internees, where great families, sentenced multiple times over, inextricably linked their fates,” says Sula. Human dignity, she adds, of the “Great Houses” – Markagjoni, Pervizi, Bajraktari, Dukagjini, Kokali, Dine, Vatnikaj, Koliqi, Biçaku, Mulleti, Alla, Merlika, Topalli, Alizoti, Matjani, Kupi, Dosti, Kaloshi, Tinaj, Kolgjini, Sina, Bami, Mirakaj, and dozens of others, including those of five Albanian prime ministers: Koço Kota, Fejzi Alizoti, Mehdi Frashëri, Mustafa Merlika, Fiqiri Dine – was overcoming the cramped spaces of the barracks. There, the Albanian translation of Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso” (40,000 verses) by Prof. Guljelm Deda continued, the voices of children born in Savra were heard, and hope was winning over everything with its inexplicable laws.

This proximity of the “overthrown classes,” this gathering that regularly lined up for roll call and was subjected to the harshest agricultural labor during the day, was soon seen as a real threat by its “architects.” The elites had gathered in the same place – and such a high concentration of sound minds constituted a threat in their eyes. They were not ordinary opponents, so it was decided that Savra would be dispersed into many villages across the marshy zone, and the punished families would serve their 5-year internments there.

Sula marks that villages like Çermë kamp, Çermë sektor, Grabian, Gradishtë, Kryekuq, Karavasta, Bedat, Plug, Gjazë, Rrapëz, Kolonjë, Dushk, Zhamë, Sulzotaj, Karbunarë, etc., were turned into internment centers. The Internment-Deportation Commission would meet and decide to extend internments whenever members of these families reached the final days of their given sentence, which was usually 5 years at a time.

PRISONS WITHOUT BARS, OR CAMPS?

Black-and-white photos of crossed fates, grandmothers in black headscarves, barracks where people lived like in matchboxes, stand across from color photos of the villages today. What is it like to see the prison in color – that vast prison where scorching summers and freezing winters passed? In the eyes of those who lived there and are alive today – more than tears, there is a visible void. It is the void of contradictory feelings; between longing for a youth that passed and the peace of won freedom. Once, Albania for them was merely a cluster of barracks; today, Albania is a homeland and pain, it is longing and tears, it is the sadness of what could have been better but has remained just slightly more than a large barrack.

Even the barracks themselves have somewhat vanished. In some places they are plastered, in others they are falling apart. Internees were lined up every day for the roll call at scheduled times and were prohibited from moving outside the village where they lived. For movements outside the village, they had to be provided with a permit from the operativi (security officer). Their jobs were the hardest on the farm, and social life deprivations were always present.

In this context, Sula asks: can the aforementioned villages of the “29 Nëntori” farm be considered labor camps? Or were they internment centers? “Or were they prisons without bars? During the documentation process today, 30 years after the fall of communism, we photographed the water line in Gjaza, which was the border point that internees could not cross. Even the water line in Gjaza has its own untold story of the border.”

“What about the arrests of internees, being led in handcuffs from the security officer’s office, or the denied permission to be buried in one’s birthplace – as in the case of the late Mark Temali – how do these affect the naming of these internment centers where over 700 families spent their lives, as documented by the Institute for the Integration of Political Persecutees?” asks the Chair of the Authority.

For her and many others dealing with the fates of the past, there are many complex questions and answers from the recent past, which deserves to be known, told, studied, documented, and, by being narrated in sites of memory, made visitable for the youth and generations to come.

Regarding the above, she says that the Authority has undertaken the construction of a comprehensive narrative for the labor camps/internment centers in Lushnje, based on the documentation of yesterday and today, and on the family and individual stories of the internees. “Creating profiles of those born in internment. Their stories that began in Savra, Gradishtë, Plug, and other villages and are written today all over the world, with their life and professional experiences,” she says, adding: “Turning into sites of memory the houses, dwellings, buildings, and bachelor barracks in the internment villages of Lushnje, Divjakë, and Fier, with memorial plaques that speak to our present and clearly tell this untold story to the generations – the story of the area where 90% of the system’s political opponents were interned.”Memorie.al