By Jonida PLAKU

Part One

Memorie.al / History is full of labyrinths, and no one can claim to walk through it in a straight line from the beginning, following every detail that it carries within the lives of people. Especially when its paths are closed or obstacles are placed by those who, after declaring themselves victors, wrote it as it suited their interests. In the span of 50 years, truths cannot be easily “buried,” yet describing them as they truly were is no easy task for a journalist. But when you encounter the portrait of one of those – even if the description was made by his opponents – and meet him again with the grandeur of a man who grew with the times, conscience and professional duty push you into the unknowns of his life and of those who surrounded him.

None of the children of the past could have imagined that he, “Sali Protopapa” from the film I teti në bronz (The Eighth in Bronze), who clashed with “Commissar Memo” and displayed the manhood and character of a fighter and commander carved as an Anatolian and somewhat unrefined, would be a future scientist in America’s most prestigious institutions.

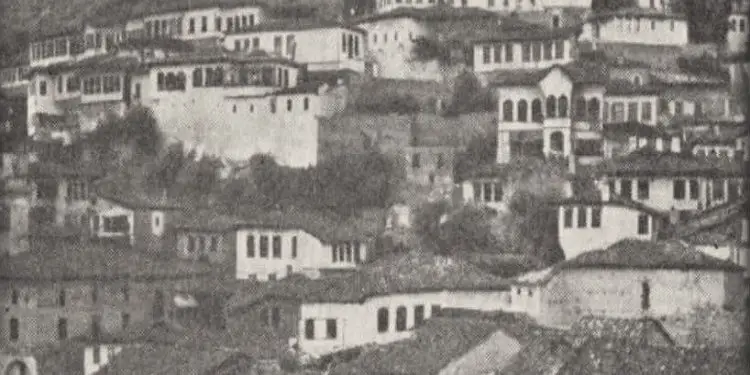

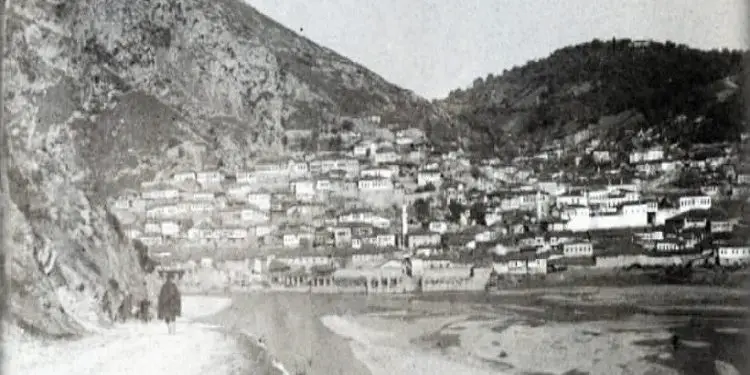

Even more so, that after many, many years, he would return to Berat more triumphant than the victors – not in terms of a warrior’s creed, but in terms of character, love for people and his birthplace, and the desire to see a freer, more civilized, and more democratic Albania than the propaganda that held it more than occupied during the years of communism.

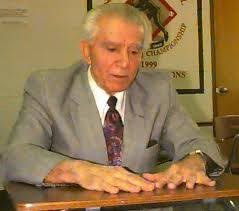

The character who prompted me to rewrite what has been written about more than once is named Sejfi Protopapa. He is the man who’s CV, as a colleague described in a previous piece, wanders between Berat and Wayland, Massachusetts – between World War II and a completely new life in the USA. This is not out of a desire to mechanically repeat or awaken his image, but with the tendency to add something new to our knowledge of that man and our history in particular.

I began to slowly uncover his non-physical portrait – as it seems the director hit the mark with the film character – by shaking off memories and removing the forgetfulness wrapped in fabrications and lies, which false ideals still hold up like outdated curtains in a museum window, preventing you from seeing the relics inside.

“Sali Protopapa” from the film I teti në bronz left a negative taste for some, as they saw him collaborating with the Germans or as a meat-eater; for the generation that did not live through the war and did not know its actors in detail, he had a negative impact. This occurred despite the authors remaining stricter regarding the character’s manly nature, unlike the typical politics of Socialist Realism art in those years.

But why did the great writer, Dritëro Agolli, in his screenplay, despite the circumstances of the time, give us such a vivid portrait that many former fighters thought they were seeing themselves in the actor representing “Sali Protopapa”? This happened with Maliq Dushari, Avni Protopapa, and even Sejfi Protopapa himself, who believed that they were the very type and character of the personage in question, without the artistic and ideological robe draped by the requirements of Socialist Realism or the victor’s idea of superiority over the loser.

And if in this history of art and reality there are many conjectures and questions, the curiosity is satisfied by the director himself, Viktor Gjika, in his interview and memories of the film and the portrait of “Sali Protopapa.” Even Sejfi Protopapa in his memoirs does not forget to give details about his meeting with the writer Dritëro Agolli, where they drank more raki than is shown in the film.

Sixty years after his departure and as many from his life, education, and activity in the USA – after the writing and rewriting of his figure in our minds, sometimes crowded with one-sided information and sometimes filled with things we had no chance to compare – it now remains for us to write a history different from what we were taught, because reality is quite different.

“Sali Protopapa” and the real person, Sejfi Protopapa, who visited Berat in 1992 and today lives in the USA. But who is Sejfi Protopapa? What was his activity in Berat and beyond, and what was his struggle? Why and how did he leave Berat and Albania in 1944? What divided and what united Sejfi with Kristaq Tutulani, Bajram Xeba, Dane Cukalati, Resul Dollani, Namik Mehqemeja, Fatbardh Guri, Neti Fuga, etc.?

What was truly the war against the Italians, and why did Sejfi try to leave Berat before Italy’s capitulation? When and how did the relations between the groups acting in Berat break down, and how did Sejfi Protopapa leave to escape a potential execution?

“My life in the city of a thousand and one windows”

His name is registered among the ten most prominent Nuclear Physics scientists in the United States of America. But even though he has a good life with high standards in the most developed and democratic country in the world, Sejfi Protopapa cannot forget Berat, the city where he was born and raised.

The city where, alongside his first lessons, he also received the first blows to his newly started career in the struggle for national interests, during those years when the world war was at its peak for the warring parties. The reason for his departure was his differing beliefs from those who were on the verge of victory; their ideas did not align with the side he belonged to regarding how the future power should be administered.

For Sejfi Protopapa, Resul Dollani, Namik Mehqemeja, and Vangjel Myzeqari were friends since primary school, as was Margarita Tutulani, the heroine who was executed and who remained in his mind for her beauty, with which all the boys in the class were in love, as he writes in his memoirs.

Despite being aligned with the losers of the war, and Margarita (after her death) with the victor, Sejfi Protopapa cannot deny the truths after more than 60 years. For him, Margarita was beautiful and combative, and her brother, Kristaq, and other friends have remained in his memory.

In the memoirs of the great physicist from Berat, an important place is held by his connection with Kristaq Tutulani and the help he gave him in printing leaflets – something that did not escape the eyes of the Italian fascists. Kristaq was arrested a few days before the capitulation and executed in Gosë, Kavaja, together with Margarita. Meanwhile, to escape arrest, Sejfi Protopapa fled Berat toward the village of Protopapa in the Opar region, Korçë, where he had some of his father’s friends.

On the way, while at the Kulmak Tekke, he learned of Italy’s capitulation and returned again to the city of Berat to resume the work and the struggle they had started.

From the Memoirs of Sejfi Protopapa

“Before the arrival of the ‘Blackshirts,’ the prefect of Berat was Qazim Bodinaku, a loyal servant of King Zog, who was entrusted with keeping under surveillance all citizens who had participated in the Fier Uprising of June 1935…! Mr. Bodinaku’s children, a son and two daughters, came to school accompanied by an armed guard who waited outside the classroom door until the lesson was over.

Margarita Tutulani, Resul Dollani (Toxhari), Namik Mehqemeja, and Vangjel Myzeqari were some of the other students in my class. All the boys in the class were in love with Margarita. She was very beautiful and, at the same time, the best student in our class…! The Italian occupation stimulated economic activity compared to the stagnant time of King Zog’s regime.

The creation of the Fascist Party and the Balli Kombëtar in 1939, as well as the birth of the Communist Party in 1941 (only after the German army attacked the Soviet Union), created confusion in the political preferences of all Albanians, especially among those who had members with opposing preferences within their families.

In our house, there was no confusion regarding the prediction of which side would be the winner of the world war. We were convinced that the combination of the Great Russian army with the industrial and military productivity of the USA would eventually emerge victorious…!

Shortly before the capitulation of fascist Italy in 1943, the carabinieri arrested a number of young people in Berat and later executed them. Among them were Margarita Tutulani and her brother, Kristaq. At this time, I was helping Kristaq print anti-fascist leaflets. When I heard of their execution, I left Berat and headed toward the village of Protopapa (Opar region, Korçë).

There, my father’s tribe could offer me a safe haven. Born with a hip defect, I traveled slowly with the help of a cane. On the way to Protopapa, I stayed one night in the tekke located on the snow-covered peak of Mount Tomorr. There I learned of Italy’s capitulation, and within a day, I returned to my home in Berat…”

The Beginning of the Great Divide

For Sejfi Protopapa, the relations between the nationalist groups and those of the National Liberation Front in Berat were normal, with some minor differences, until the time of fascist Italy’s capitulation. After German troops entered Albania, the situation began to change, he recalls in his notes of the years up to 1944, before he left Berat. According to him, “…it is an undeniable historical fact that the German army was never stationed in Berat.

To secure oil production, they had stationed only 100 soldiers in Kuçovë…”, recalls Sejfi Protopapa, and further adds that “…the Germans were grateful to Xhafer Deva, a devoted Nazi Albanian, who managed to govern the country in a way, thus contributing to the protection of the supply arteries of the German army.” Sejfi Protopapa recalls that after the capitulation of fascist Italy, the situation in Berat was somewhat confusing./Memorie.al