Memorie.al / The distant past seem to arrive in the form of a somber legend from the mouth of 82-year-old Skënder Stefanllari. One of the survivors of the prisoner camp in Vloçisht, he still holds vivid in his memory the days of terror spent in the post-war Albanian “Auschwitz,” during the attempts to drain the Maliq marsh. Stefanllari, with the serenity of age, manages to reconstruct many memories. Many names and characters come alive, just as pain has carved them into his memory, making them inseparable from his days and nights now, nearly half a century later.

Once, the Marsh…!

“They say the Maliq marsh used to have many ducks, geese, fish, and eels,” Stefanllari begins his narration. “The residents of the surrounding area secured their bread by hunting such species. There were those who entered the marsh on foot, just as there were others who had bought boats. The marsh had a depth of 6 meters. From time to time, news arrived that the water had swallowed human lives. It is said that finding drowned bodies in the marsh was quite difficult. All of this happened in the summer, when people tried to fish for eels and hunt wild birds while having to endure the swarm of mosquitoes. In winter, the marsh froze and was covered in ice,” recalls the former prisoner and political persecutee.

“The residents built devices they called sane, similar to today’s skis, using horse leg bones. They would mount them and, aided by two sticks with nails at the ends, they would venture into the depths to hunt ducks and geese. They say that even horses passed over the thickness of the ice, which was substantial. Years ago, a caravan of 30 horses and 30 men remained inside the marsh. They had crossed in the morning over the icy path to go to Bilisht. When they returned in the evening, they did not realize that the south wind had melted and severely weakened the ice’s strength. The marsh swallowed the entire caravan at once. Throughout the winter of that year, the drowned bodies were sought, sometimes covered by snow and sometimes by ice. Years have passed since its reclamation, but residents of the surrounding areas say the lake had great, inalienable values,” Skënder recalls.

The Draining of the Marsh

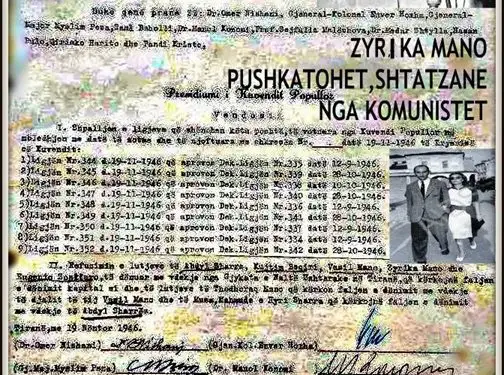

“The draining of the marsh began in 1946,” Skënder Stefanllari continues. “Even King Zog had such a project. There was much dreaming about this kind of project, but there were neither the means nor the funds. The engineers of Korça opposed its draining; the idea was put forward that the marsh should be maintained. But the Albanian Communist Party had arrived on the political scene. The Party was to empty the marsh water in just 6 months. The word of the communists was never questioned. The series of actions began as promised. In the middle of the marsh, songs and accordion melodies were heard. Delegates from Tirana came and went endlessly.

The only words heard from their mouths were, ‘Look at what the Party is doing for you!’ But what happened was something the Communist Party had not foreseen. The draining of the marsh failed. This was more than terrible. It wasn’t the draining of the marsh that had failed, but the Party. To save its honor and the slogan that ‘communists capture every fortress,’ the saboteurs were found one after another…! They were not few, but an entire hostile group that wished well neither to the people, nor the Party, nor Comrade Enver. From the secret offices of the party came the order: ‘Punish the saboteurs and bury them in the marsh.’ And a portion of the ‘enemies of the people’ were buried alive,” Stefanllari says.

“The second phase of the great project to drain the Maliq marsh began. This time, let the enemies of Albania dare. The marsh had room for others to be killed…! The draining of the marsh was completed. 5,500 hectares of new land were gained. The Maliq Agricultural Enterprise and the town of Maliq were established. The town and the agricultural farms were populated by residents of mountain villages. In 1951, the Sugar Combine was built, which included the Alcohol Factory and the Starch Factory. The gained field was planted with beets, wheat, and corn. The draining of the marsh started two years after liberation. About 6,000 volunteers (aksionistë) worked for its draining,” the former persecutee continues.

“Amidst Tortures and Hunger, We Ate Beets to Survive!”

“Among the prisoners was Father Jorgji Kosta Bezhani,” recalls Skënder Stefanllari. “He would go to work and return from there only in silence. For him, the residents of the village of Bezhan say he was an extraordinary man. For years they had adored their Father, but they could not come to the Vloçisht camp to see him. The Father remained lonely. To his sadness was added a corporal who mocked Father Jorgji Bezhani every day. Unable to bear it any longer, he said to him: ‘Do not pinch me, you wicked man.’ That alone was enough for a man to die. The priest had insulted the corporal.

Through the captor, the party had been insulted. Worse still, the party had been insulted by an enemy of the people. From that moment on, his beatings began. It is impossible to say what methods were used against Father Jorgji Bezhani. The prisoners heard only his screams, until his voice faded away and was no longer heard. From that day on, the priest was never seen again, either alive or dead. All the prisoners had been badly beaten that day. But what could they do? Father Josif Papamihali from Elbasan suffered the same fate. From morning to evening, they felt only the hunger for bread. They were all hungry, barefoot and unclothed, among mosquitoes. This sight pleased the party, because it saw how people who did not want its good suffered.

When we returned from work, we passed through the fields planted with beets. Beside and behind us were police accompanying us to the workplace? Everyone dreamed of reaching down and pulling out a beet to eat. You could do such a thing, but if they saw you, it was certain that death awaited you that very day. I remember when a prisoner, a young boy, could not resist the hunger and reached down to pull a beet from the earth. I remember how they ordered us to march over his body. That scene never leaves my mind. The boy had pulled the beet and was ready to bite…! After two days, he died. Another case, similar to the first, was when a friend of mine was pulling a beet; the prisoner pulled the beet and did not let go of it. He bit the beet even though the policeman’s whip fell upon his head,” recalls former political prisoner Stefanllari.

Beside the Volunteers, Another Camp…!

“The volunteers worked barefoot, and in the evening, to the sounds of an accordion or a bagpipe, they danced and held balls. The volunteers were one side of the coin. The latter initially slept in tents and then regular camps were established. These were the young volunteers who worked with song, with joy, without pay. This was the beginning of building the class-pyramid of socialism. The volunteers learned to read and write. Work, celebration, and school. In the action, there were no age or gender restrictions. All would be residents of the future town of Maliq…! The volunteer camp was buzzing and boiling, but what was happening in another camp that the Party had set up for the draining of the marsh?” Stefanllari recalls.

The Marsh Where the Bones of 63 Political Prisoners Remained…!

“Not few, but about 1,800 political prisoners – merchants, engineers, clergy – spent the summer of their imprisonment in Vloçisht. This camp ‘ate’ 63 convicts,” says the survivor of this camp, Skënder Stefanllari, 82 years old.

The Execution of a Generation of Professors

“In 1946, the works for the draining of the marsh failed. Sabotage was invented. I was in the Vloçisht camp for 6 months of the summer of 1946. In winter, they put us in the cells of the Korça prison. In 1946, the marsh ‘ate’ all the students of ‘Harry Fultz,’ the engineers Abdyl Sharra, Kujtim Beqiri, Aleks Alarupi, Pandeli Zografi, Llambi Napuçe, Mihal Stratobërdha, etc. The political prisoners were assigned to the construction of the large Maliq Bridge. The bridge ‘ate’ Professor Bego Gjonzeneli, the youths Burim Kokoshi, Klito Lamaj, Fadil Xhindi, the jurist Mark Temali, Zihni Dervishi, Xhorxh Koçi, Sezai Gora, Petro Zisi, Petrit Kadilliu, Muharrem Xhixha, and many others like Hiqmet Cerloi, Ali Tirana, Besnik Duro, Tefik Gabrani… A total of 63 victims. We went out to work by count and entered the camp by count,” Stefanllari says.

“Vasil, ci rivedremo al cielo”

Among so many executions, Skënder recalls the moment of the execution of the couple Vasil and Zyrika Mano. “They were a wonderful Macedonian couple. That couple was adored by everyone. The days passed, and every day they drew closer to execution. We waited with pain for their final day. That moment arrived. Not much could be said, and Zyrika chose the words in Italian, ‘Vasil, ci rivedremo al cielo‘ (Vasil, we shall see each other again in heaven), to say to her husband. The military prosecutor, Nevzad Haznedari, answered them: ‘You will see each other in your mother’s [hell]!’. Other people, in various ways but with the same sense of pain, would go toward execution,” Skënder Stefanllari continues.

Before Death, Even Spittle!

“Muharrem Xhixha from Kruja was killed because he crossed the embankment of the canal. For personal needs that he did not want to perform in front of his friends, he stepped away a little further, but the policeman thought he was going to escape and shot him with a firearm. Virtyt Gjylbegaj from Elbasan was killed near the wires that surrounded the barracks where we were serving our sentence. The lawyer, Qani Sulejmani, had his arm broken with a shovel because he could not fulfill the quota. With a shovel, Colonel Sulejman Vuçiterna, who died in the camp, cut his own toes. For political prisoners, various punishments were given, unheard of in any country in the world.

One such story of punishment happened with Niko Kirka. The latter had written a letter to his father where he said: ‘white days will come even for us who suffer in the Vloçisht camp.’ The letter did not go to his father but fell into the hands of the Sigurimi. They took Niko and tied him to a tree early in the morning. They ordered all of us to spit in his face because, according to them, ‘white days would never come for us prisoners of Vloçisht.’ About 1,800 spits were poured onto Niko’s face. We did not want to spit, but whoever did not spit would be punished more severely than Niko himself.”

“Show the Gold, or You Will Die in the Marsh!”

“The merchants were tortured in all the possible ways the human mind can conceive. All of this was pressure to show the gold they had hidden. The Party thought they were people drowned in gold. ‘If they wanted their lives, they had to hand over the gold,’ the 82-year-old recalls. Whether they had hidden gold or not mattered little to the Party. The merchant Sotiraq Lako was left dead in the marsh. They covered him in the middle of the marsh. The same fate befell the merchant Kosta Fundo, Bexhet Frashëri, etc. It was impossible to withstand such tortures. One day when we went to the barracks, we found the merchant from Korça, Koçi Misrasi, hanged. His only gold was just a few gold-capped teeth. When we buried him, we noticed that his gold teeth had been ripped out,” the former convict says.

Accusations Against Skënder Stefanllari

“I,” Skënder says, “along with Qemal Çoçka and Petrit Qyteza, was young at the time. Until then, we had escaped beatings and punishments, but apparently, we too had been put on the list. One day a policeman passes and fixes his eyes on me, saying, ‘Where are you, prosecutor?!’ I couldn’t understand anything, but very soon I would find out as they would explain everything to me. According to them, I had set up a judicial body, with Niko Kirka as the chief judge, while I myself was the prosecutor. The Sigurimi supposedly even secured information that we had held a court session where we had sentenced the camp guards and all other Party cadres to death. Even though I was strong, they beat me badly. Corporal Murati grabbed me by the throat, jammed his two fingers into my eyes, and became enraged.

I threw him into the mud, but the policeman Hazis Halla jumped on me. I threw him into the canal too. The canal was 3 meters deep. I defeated policeman Jaçe from Maliq as well, but policeman Alushi grabs a shovel and hits me in the head. I fall and am covered with sludge. The whistle blew for the end of work. They pulled me out of the sludge. It was July 1948. As I was half-dead, they put me on the back of my friend Alfons Dovana, an hour’s walk to the camp. Alfons was weak, but he kept me on his back. For three days I remained unconscious. From death, I was saved by the prison doctor, Isuf Hysenbegasi,” Skënder Stefanllari concludes his tragic story, stating that what he has told from his memories is only a drop of water in the great ocean of pain!/Memorie.al