By Njazi Nelaj & Petrit Bebeçi

Part Two

– That morning, fate was not with the Commissar! –

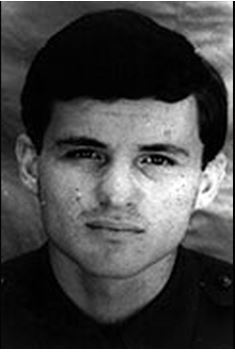

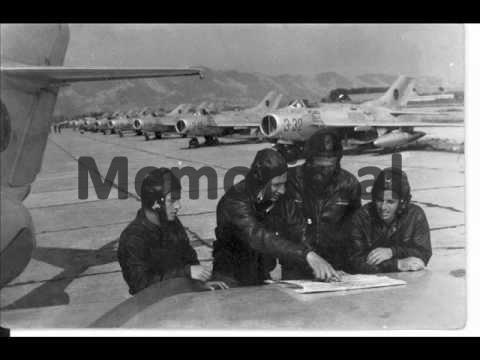

Memorie.al / Luto Refat Sadikaj enter the ranks of the “elite” pilots of Albanian aviation of all time. He was one of the pilots of the first group that was trained, from the very beginning, at our aviation school in Vlorë. Thus, Luto Sadikaj is a “domestic product,” one hundred percent. Not only that. Luto Sadikaj was “molded” and perfected up to the sophisticated aircraft of the time, the MiG-21, in Albanian airfields, with local instructors, according to the combat preparation course and Albanian aviation regulations, under conditions where limits were constantly decreasing and without having two-seater aircraft. We are perhaps dealing with a unique case in the world history of combat aviation.

Continued from the previous issue

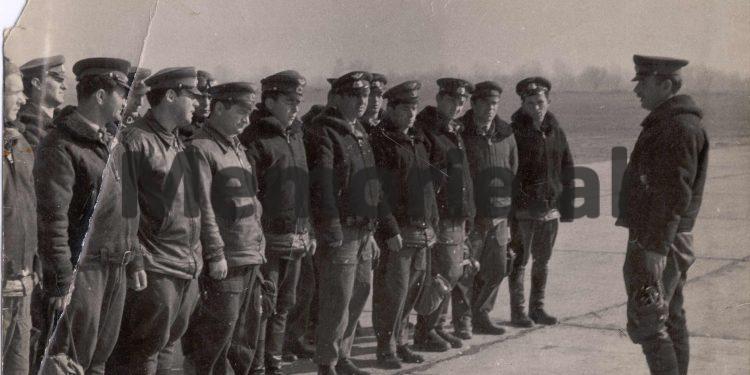

“The country’s air force had been strengthened with the most sophisticated fighter jets of the time. The hopes of those who did not wish us well had turned to dust and ashes. The following year, 1972, marked intensive preparation for the qualification of pilots who transitioned to ‘MiG’-21 aircraft in China; meanwhile, work was carried out in parallel with a group of promising pilots to transition to this type of aircraft here, in our country, at the Rinas airfield. This was a task being performed for the first time. Young pilots, aged 22-23, were selected, who stood out for their high piloting technique and who had clear potential.

At that time, pilot Luto Refat Sadikaj was flying supersonic fighter-bombers ‘MiG’-19 S, during the day, in simple weather conditions. The goal was for him to achieve the second class of military pilot. With his characteristic will and persistence, Luto Sadikaj was included in the group of pilots transitioning to ‘MiG’-21 aircraft, along with his comrades: Dhimitër Robo (‘Martyr of the Homeland’); Klement Aliko, Musa Kame, and Kujtim Kryekurti. Their instructor was one of the most prominent pilots in the country, Gëzdar Veipi. Luto Sadikaj excelled in this case as well and became an example for his colleagues, both in theory and in flight. His rare talent and abilities stood out and shone powerfully.

Luto Sadikaj was a pilot with high and steady piloting technique. He was such not only when everything in the air went well, but also when he found himself facing the unexpected and adversities. Indeed, in such cases, the personality and true values of the pilot were seriously put to the test. Special events in the air occur rarely in a pilot’s life, but when they appear, they test his talent and values. Unfortunately, in Luto Sadikaj’s flying life, unexpected events followed one after another.

In a flight with the ‘MiG’-21 aircraft, after he had taken off from the Rinas airfield at night in simple meteorological conditions, when he had reached an altitude of 100 m and had retracted the wheels and flaps normally, Luto heard that the noise penetrating the cockpit where he was suddenly changed. The cockpit canopy was rising. With his hardened physique and arms full of muscle, he tried to lower the canopy and insert the pins into the sockets to then fix the canopy hook, but with one hand, this was practically impossible. The aircraft had to be steered with the other hand.

As the aircraft was in the climb regime, it was increasing speed, and the lifting force increased to the point where the powerful air currents ripped the canopy off the aircraft. Further piloting of the plane became extremely difficult. Almost impossible. In the ‘MiG’-21, due to its design, after the canopy detaches, the aircraft does not protect the pilot from the powerful air currents. Luto was left only to protect his head using the armored glass above him, which protects the pilot from projectiles. But even this glass is placed 30 cm further from the pilot’s face compared to previous aircraft. The noise of the air currents drowned out that of the engine and created a white curtain before his eyes.

The forces acting on the plane tended to pull Luto out of the cockpit. The flight speed fluctuated from 300 km/h, which is the minimum speed, up to 1000 km/h. The noises had blocked the radio exchange between the pilot in the air and the flight leader on the ground. The pilot tried to set the progressive speed of the aircraft to 500-600 km/h but found it difficult. He lowered the wheels. The aircraft began to fly steadily. Thanks to his rare values as a man and as a pilot, Luto Sadikaj succeeded in landing the aircraft, without a canopy, at the takeoff airfield, within normal parameters.

Referring to Luto’s traits, I can say that he was favored by: high technical-professional abilities, courage and bravery, resilience in the face of the unexpected, and manhood, which gave him the opportunity to emerge with honor. After landing, when he tried to release the braking parachute, the air currents slammed his hand back. After stopping the plane, he turned off the engine, untied the straps, and exited the cockpit. He did not descend by the ladder but jumped from that height without waiting for them to bring the ladder. We saw him disfigured; he kept his eyes closed. ‘It feels like I have sand in my eyes,’ he told me when we met him and congratulated him for returning safe and sound.

Among the hugs of his comrades, someone asked him: ‘What went through your mind in those moments?’ In that fortunate moment for him and us, his comrades, he told us: ‘I only remembered Gresa, my eldest daughter; instead of the gyro-horizon (the central and most important instrument on the instrument board), her face appeared to me.’ Cases similar to Luto’s are rare and usually end in an air catastrophe. Luto Sadikaj survived the situation and emerged victorious over it; he brought the multi-million dollar aircraft to the ground and preserved the most precious thing – his life. The act Luto Sadikaj performed was heroic, but not the only one.

In another case, while flying the MiG-21 at the Gjadër airfield, Luto Sadikaj faced a very grave air situation. He was flying during the day in simple weather conditions. His task was to reach a flight speed twice the speed of sound at an altitude of 13,000 m. The maneuver for gaining altitude and reaching the specified speed was constructed according to a scheme that passed far from inhabited centers, to avoid the destructive effects caused by the shockwave after crossing the sound barrier. When the speed of the aircraft Luto was steering reached 1920 km/h (M=1.8), the aircraft engine changed its noise. It began to run unsteadily.

According to the rule, pilot Luto Sadikaj reported via radio to the flight leader on the ground. He instructed him to reduce the flight speed by disengaging the afterburner, which releases additional engine power. Luto acted immediately, but in a few seconds, the aircraft began to oscillate around the horizontal axis. Luto’s head was struck hard against the canopy in the upper part, and the pilot was dazed. Although he had a helmet on, a visible mark remained on the canopy. The speed of the aircraft was constantly increasing; it passed 2150 km/h. The afterburner did not disengage, and the aircraft was headed toward destruction. We were at the airfield following the air situation through the radio exchange between the pilot in the air and the flight leader, and we observed the contrail. A terrifying situation was created, and we were quite worried. Our calm returned only when we saw that our comrade had ‘tamed’ that ‘rabid beast.’

After the normal landing on the ground, for several days in a row, the aircraft that presented the aforementioned defect underwent detailed checks of all systems and aggregates. The aircraft technician, the brilliant and golden-handed Gani Villa, noticed that the cone had been installed backwards. The error had been allowed by the specialists of the aircraft’s factory of origin, who performed the medium repair of this type under workshop conditions and did not allow a flight test of the repaired aircraft.

We knew well the values of Luto Sadikaj as a man and as a pilot, so our conviction was reinforced that only he could cope with that defect of a very dangerous nature. What happened to Luto did not even favor abandoning the aircraft through ejection, because the flight speed and the altitude at which the aircraft was located were far beyond those recommended. Luto Sadikaj was sincere in his relations with colleagues and subordinates. After every flight, he would sit among them and analyze every incident or deviation from parameters in detail.

By openly revealing the allowed shortcomings, he became a good example and a source of inspiration for the regiment’s personnel and beyond. He gave his personal example also by flying in the ‘MiG 21’ aircraft together with his colleagues of the third squadron, while serving in the duty of the regiment’s commissar. Luto participated in all tasks according to the program and there was no occasion where he avoided flights; rather, he sought them. In this type of aircraft, since 1974 when Dhimitraq Robo (Martyr of the Homeland) fell in the line of duty, no premise for an extraordinary event had occurred.

The aircraft technicians and aviation specialists were of an enviable professional level and ability. They were refreshed from time to time with younger ones from the intakes of the Aviation Academy. The age of the technicians and pilots of the third squadron was young, and brotherly relations of mutual trust were established among them. They were good friends with one another, not only within the unit.

On March 29, 1982, on the day when the Gjadër regiment had gone out to fly during the day in simple weather conditions, with the task of practicing pilots to intercept and attack aerial targets, Luto came to the start (the place where aircraft stay, are sent off, and received) shortly before the flights began. The duty of the Regiment Commissar, in addition to flights like all pilots, obligated Luto with various other duties of a non-flying nature. I was his subordinate, but I was also his dear comrade and friend.

Not just when we joined the Gjadër Regiment, but since 1959, when we went to the ‘Skënderbej’ Military School. I spoke openly with him and with the kindness of a good friend. Before he boarded the plane, I said to him, socially and with a laugh: ‘Next time, I will not allow you to fly if you do not respect the pilot’s daily regime!’ He answered me, also with a kind tone: ‘Yes, I will do as you do; leaving everything before the flight and preparing as if you was a simple pilot. For we have come to fly since 1959; not for positions!’

Before entering the cockpit of the ‘MiG’-21 aircraft, with side number 108, the aircraft technician reported to him according to the rule on the readiness of the air vehicle and helped him get settled in the cockpit and strap in. I couldn’t resist. I climbed the ladder and followed the actions of both. Every action of theirs was precise and in order. Pilot Luto Sadikaj started the aircraft engine and tested its systems under load. After being convinced of their regularity, he signed the control sheet, which he handed to the technician.

I tapped him lightly on the helmet and wished him, with words and from the heart: ‘Have a good flight!’ I saw the cockpit canopy close and descended the ladder. Then Luto took permission from the flight leader and released the brakes, and his plane moved forward to enter the takeoff strip. The aircraft technician, I, and everyone present at the start saluted, as is usually done at this solemn moment. The aerial object which Luto was to intercept and attack was of the same type and had taken off 5 minutes earlier.

On the takeoff strip, pilot Luto Sadikaj positioned the aircraft straight in the center of the runway, stopped it, and performed the final check so that the engine gave 100% power and the aircraft controls moved freely. He released the brakes and began to increase engine power to the maximum. We accompanied the takeoff with our eyes and heard the regular work of the engine by its noise, which we knew. The aircraft took off from the ground at the designated spot and at a normal angle. What happened next was fatal and without an exit.

When aircraft 108 was at an altitude of 4-5 m, we heard a powerful explosion in the aircraft engine and the aircraft was not moving away from the ground. The pilot tried to gain altitude, but the engine power was insufficient and the aircraft did not obey the pilot’s actions. We could imagine the meaning of that unusual noise, so we were extremely worried and gave the alarm. Fire trucks, the ambulance, and the ready vehicle, which is put into motion in cases of emergency, set off quickly for the northern end of the airfield. Luto Sadikaj was facing a severe defect and in a critical situation where the way out was limited.

With quick reflexes, he decided to land the aircraft directly ahead on the takeoff strip. The aircraft’s speed at that moment was 380-400 km/h and the aircraft touched the ground 150 m after leaving the runway behind. The aircraft passed the green belt, which is 500 m long, passed the sand belt which is a security belt and serves for breaking the aircraft, went outside the dimensions of the Gjadër airfield, and stopped near the embankment of the Gjadër River in a semi-overturned position.

At the place where the aircraft stopped, two villagers from Gjadër were the first to go for help. Luto, trapped in the aircraft cockpit, signaled to the villagers to break the blocked canopy, but they could not do this with the tools they happened to have in their hands. Knowing the danger, in that grave situation for his life, Luto Sadikaj, as a man with a great soul and heart, signaled the two Gjadër villagers to leave quickly, and… After 29 seconds, or after 60 seconds from the beginning of the movement to take off, the ‘MiG’-21 aircraft, with the pilot in the cockpit, exploded.

Thus fell, in the line of duty, the commissar of the Gjadër Regiment, the talented pilot Luto Refat Sadikaj; a dedicated parent and husband, extremely correct; a simple man; one of the simplest I have known in life. He did not separate himself from his passion for flight but rose in every case and for every task as if he were a young man and performed all the tasks of the flight program with the ‘Mig 21’ aircraft.” Memorie.al