By Raimonda Moisiu

Part Two

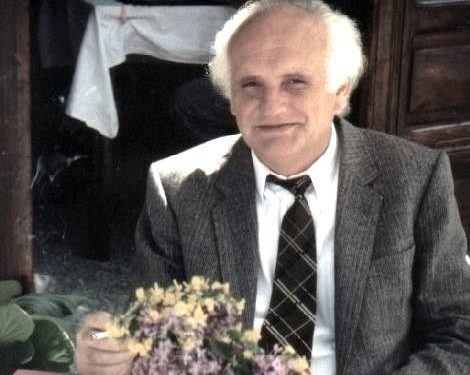

Memorie.al / Dr. Ilinden Spasse are the son of a writer, which means a great deal to him, as he was born alongside literature and the art of writing. He is the son of Sterjo Spasse, one of the most prominent Albanian writers of the 20th century – a powerful bridge between the Albanian and Macedonian nationalities, a modern writer who evoked peace and harmony between nations. Both father and son are pioneers of Albanian letters, appearing as if they emerged from a historical museum of Albanian literature. Beyond Dr. Ilinden Spasse’s natural inclination, his inspiration for writing stems from life’s dreams and experiences, with their internal voice and individuality.

He is a prose writer with a magical power to parade a large number of characters – both simple people and those in power. He reveals not only their lively characters in the past and future but also recounts their freedom with subtle, sensitive humor and artistically sharp sarcasm. This has turned Ilinden Spasse into a master of narration, much like his father. He has published novels and short stories, among which the monographic work “My Father, Sterjo” stands out.

In the field of translation, he brought Michael Hart’s “The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History” to Albanian readers. At the end of July, I met Dr. Ilinden Spasse and his charming wife, Maria, along with writer and poet Përparim Hysi in Tirana. It was a “writers’ coffee,” where the main topics were literature and literary criticism. He gifted me his latest novel, “The Philosophers’ Pavilion.” I particularly wanted to ask him about his father’s literary creativity and his own early writing career. In this interview, the well-known and talented Dr. Ilinden Spasse speaks about himself and his father, the distinguished scholar Sterjo Spasse.

Continued from the previous issue

- As a writer, he [Sterjo Spasse] tackled a wide range of social issues across his entire body of work. In his novels, we find an analysis of all the reforms that took place during the monist period, but also his “Renaissance” cycle (Rilindësit) – a monumental work where he fully described, like no other, the entire period of our National Renaissance from historical, social, political, diplomatic, ethnographic, and economic perspectives.

He begins this cycle with the novel “Awakening” (Zgjimi), describing the awakening of national consciousness and the opening of the first Albanian schools, continuing until the raising of the flag in Vlorë on November 28, 1912. He describes the legendary battles of 1911-1912 in Northern Albania and Kosovo, utilizing both real historical figures and fictional characters. His entire “Renaissance” corpus features over 1,000 characters – a massive undertaking that cost him dearly in terms of health. After finishing each historical novel, he suffered a heart attack. Many events in this cycle also take place in other Balkan centers like Istanbul, Bucharest, and Sofia.

- As a social activist, he was always found at literary and artistic activities organized by the League of Writers and Artists of Albania, or in other promotional activities in his neighborhood or those organized by the Executive Committee of the time. He was particularly active during “Literature Month,” traveling to many districts of Albania with his colleagues. He loved taking his friends to his birthplace in the Prespa region to “boast” about the hospitality of the locals and the beauty of nature.

How did you manage to harmonize the prevailing historical, social, and political current events with your intellectual independence in this monograph?

The harmonization of the current with the historical, and the social with the political, came naturally from the intensive life of the writer – a life pregnant with broad activity in both literature and education, burdened by the many problems of the time, the hope for a better future, and the disappointments of various rhetorics.

What do you think has remained constant in you?

The only thing that has remained constant is the desire to contribute as much as possible, to write as much as possible…!

What are the essential elements of prose – in your case, the novel? The challenges you face in constructing it, creating it from the ideas in your mind for the progression of the characters. Do you present your characters from real life adapted to the time and situation, or vice versa?

Looking back at my modest creativity now at an advanced age, I notice that almost all the themes – whether in short stories, novellas, or longer genres – are from contemporary life. The characters are of the time, reaching a peak with the monograph “My Father, Sterjo,” which many people call a novel.

Did you “make the genre of the novel come to you,” or is it your preference?

The genre of the novel came naturally from the theme I chose. I never set out specifically to write a novel. I lack that “good ambition,” I would say, to write a novel just to surpass others. That doesn’t exist in me. If that “ambition” existed, the fruit of my literary creativity would surely be much more abundant.

Regarding the story collection “The Girl of the Pavilion” (1970) and the novel “Renewal” (1976) – are they fantasy or an internal mirror of the human world?

These titles were inspired by a time when I had just started my life in a remote mountain area where I was employed as a language and literature teacher in one of the deepest villages of Mat. My own youth, and perhaps the psychological preparation I received at home, were the “best medicine” to see life with optimism, to work with desire, and to touch the wounds of the time, naturally while adhering to the orientations of the period.

Spiritually, I was very motivated to be an optimist, unlike many of my peers who saw everything as dark and black. In these two books, there is no fantasy. That was what life was like, with its good and bad. That was the internal spiritual world of my characters.

Where does the strength of your inspiration lie as a writer who belongs to two eras – socialist realism and the post-communist period? What is the difference between these two eras? What attracts you most about reality and how do you concept it artistically?

To me, the difference between the two eras in the literary aspect doesn’t seem to exist. Even then, you could write, naturally within ideological frames. But no one forced you to write. You write now too, but it seems to me people write more nonsense (broçkulla) by relying on “freedom of speech.”

The combination of the present with the past, of literature with journalism, constitutes the basis of successful literature, but it is also a difficult technique to reflect on paper. How did you achieve this in the novel “The Philosophers’ Pavilion” (2014)?

Quite naturally: some seemingly small episodes poked me to find the thread of a story. These “small” episodes were perhaps related to my character and my upbringing. A friend told me: “You are a friend of a certain minister; tell him to give me the tender for the project he is building. I will give him as much as he wants, and you won’t be left empty-handed either!” In that situation, having just emerged from a dictatorial system into democracy, those words made quite an impression on me.

In fact, I stayed awake for nights. How can you ask a friend – especially a minister – to make bargains over money and tenders?! At that time, I didn’t even know the meaning of the word “tender.” That was the first spark for drafting this novel. At one point, I thought that only a madman could make such a request. So, I found the end of the novel. Between that beginning and that end, this very current and very critical novel was cooked…!

Mr. Ilinden, you are also a translator, having translated Michael Hart’s “The 100.” What pushed you to bring these personalities into Albanian? What was the secret that strongly influenced the translation of this book?

There is no big secret here. I happened to come across this book translated into Macedonian. I read it and understood many things, but I also didn’t understand many things. So, I decided to translate it with a dictionary in hand to understand it better. It was a good decision because knowing the lives of the world’s most prominent figures is a school in itself. I started translating it for myself, to learn about the scientists, writers, philosophers, and inventors who changed the course of human history. Page by page, I translated, edited, and adapted it into Albanian. When I finished, I saw I had done good work, so I published it. That’s all.

What do you think about the current status of criticism? Is there genuine criticism today? What has been the most sensitive misunderstanding during your creative career?

Regarding today’s criticism, I think I spoke a lot in my novel “The Philosophers’ Pavilion,” which I would define using the language of the novel: “If there’s money, there’s criticism; no money, no criticism!” If there’s money, there is superlative criticism; if there’s no money, there is silence. Currently, the institution that deals directly with the evaluation and devaluation of writers is missing here. The reasons may be many, but one thing is certain: writers have much more culture than today’s so-called critics.

In the field of literature, I haven’t had any misunderstandings with any editorial office. When they rejected a work, I laughed to myself because the arguments the editors gave didn’t convince me. But arguing was useless. So, I brushed it off with a laugh. Of course, inside I was seething with anger, just as my father and his friends seethed when the publishing house returned their works – a topic I treated in “My Father, Sterjo.”

Do you think and hope that the newspaper “Drita” will return?

The newspaper “Drita” has returned, but it doesn’t have the strength of the previous “Drita.” This is because interest in reading has dropped significantly – not just for economic reasons or because there are many publications dealing with literature, or because of the internet, but primarily because the institution that produced it is gone. The League of Writers and Artists, which our generation saw as a “support” for everything related to culture, art, and literary criticism, is gone…!

How have you felt facing the terrifying world of mediocrity, clans, hypocrites, and inferiority? What do you understand by the expressions “self-mutilation and intellectual suicide”?

As I said before: in the face of the terrifying world, mediocrity, clans, and inferiority, I have remained silent and laughed to myself. But my encounters with editorial offices were limited because I didn’t write so much as to become a nuisance to them or myself. During the monist period, a kind of self-censorship existed, as many strong pens suffered precisely for a word or an idea said in opposition to the orientations of the time.

As a writer, what is your concept of the nation, power, political parties, and democracy in our country?

Regarding the concept of the nation, power, and political parties – I don’t know what to say, as I haven’t thought about it much. As for democracy, I don’t believe I can express it more clearly here than I did in my last book. But I do know one thing: these concepts in people’s consciousness have blurred in this time of globalization. However, when you watch international matches where Albania plays, the enthusiasm of Albanian fans reaches its peak…!

When we say “the previous generation,” who do you have in mind? Who are your favorite Albanian and foreign authors?

In fact, when I speak of the previous generation, I always have in mind my father and his friends – not just his contemporaries but also younger ones who are the pride of our nation. The authors I liked most in my time were those translated into Albanian and those studied in school. But I want to say that the Russian school with its giants, the French school with its giants, and the English and American schools were the ones that molded us with the art of writing and appreciation. And I always forget that my own generation is now getting old.

Your future projects? What has remained as regret (peng)?

Anyone involved in writing always has projects in their subconscious that they don’t dare tell friends or even themselves. However, I have a project to publish the Bibliography of Sterjo, which includes over 2,600 entries, as well as his correspondence, which I find very interesting. We’ll see if I manage to publish them.

Your message for the Albanian intelligentsia and society today…!

The answer might be rhetorical. The creative work itself, the desire to keep it always alight, is a message for the youth. Memorie.al