Part One

Memorie.al / Mustafa Merlika Kruja was born in 1887 in Kruja and had the opportunity to study, thanks in part to the support of a wealthy benefactor like Essad Pasha, at the local rüshdiye (middle school), in Janina, and at the Mekteb-i Mülkiye (school of civil service) in Istanbul. After completing his education in 1910, he returned to Albania, having been appointed a teacher at the idadi (secondary school) of Durrës, and was later appointed Director of Public Education for the Sanjak of Elbasan. Mustafa Kruja was also active in the Albanian uprising of 1912 against the Ottomans and in Vlora, where, as the representative of Kruja, he was among the signatories of the Declaration of Independence and a member of the senate formed at that time. In 1914, he was appointed advisor for public education in the new administration of Prince von Wied, being one of his supporters.

In 1918, he was present at the Congress of Durrës and was subsequently appointed Minister of Post-Telegraphs in the new pro-Italian government. He personally favored an Italian protectorate (“The independence of Great Albania under the protection of Italy”). For him, only Italy could preserve and allow the construction of an Albanian national government through free elections, as Italy was among the states that supported an independent Albania after World War I.

In the 1920s, as a deputy, he belonged to the progressive movement that opposed Ahmet Zogu and was a close friend of the Kosovar deputies, for which he had to flee the country for a long period. Thus, in 1922, he fled to Yugoslavia after a coup attempt involving Albanians in the northwestern region.

He later participated in the so-called “June Movement of 1924,” a coup against the legitimate power. Under the administration of Prime Minister Fan Noli, he was appointed prefect of Shkodra. After the restoration of legality by Ahmet Zogu in December 1924, he was again forced to emigrate to Croatia, Switzerland, and Italy.

In exile, Mustafa Kruja was a member of the National Revolutionary Committee (KONARE), a left-wing Albanian political organization, where he represented the right wing. After several clashes with the left-wing faction over the agreement KONARE made with the Soviet Union, as well as the signing of the “Anti-imperialist Manifesto” of 1927 by former Prime Minister Bishop Fan Noli on behalf of KONARE – acts which Kruja criticized – he and his friends founded, with financial support from the Italian government, the pro-Italian Nationalist Group of Zara, in Croatia.

From that time until 1939, Kruja remained in exile and was involved in the political activities of this group, while continuing his studies and writings on Albanians, their language, and their ancient history, some of which were published in the periodicals of the time. Upon his return to Albania in 1939, when Fascist Italy occupied the country, Kruja became a senator and president of the Italo-Albanian Institute of Albanian Studies.

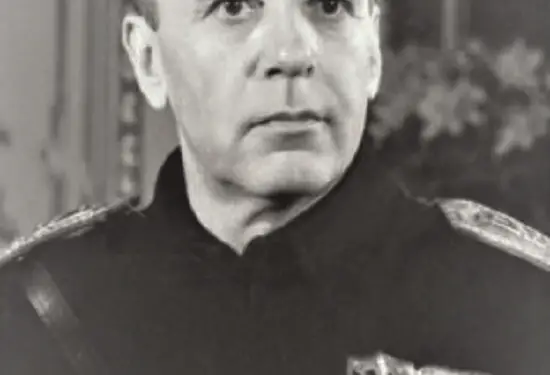

In 1941, he was appointed Prime Minister and Minister of the Interior. He resigned in 1943 and spent the rest of his life in exile in Austria, Italy, Egypt, and finally in the United States, where he died in 1958, in Niagara Falls, New York.

During his years in exile, Kruja’s anti-communist convictions were so strong that he even collaborated with his greatest opponent, King Zog I. The latter invited Mustafa Kruja to collaborate with him in Alexandria, Egypt, where they met several times with the aim of uniting the Albanian political diaspora against the communist government in Albania. According to Kruja, communist Albania would be only a small province of the Slavic-communist Empire, stretching from the Sea of Japan to the Adriatic.

After World War II, he considered King Zog I as the only one who could unite the Albanian diaspora groups and the only one who could have influence over the Albanians in Albania. King Zog I had the power to support, both financially and spiritually, political actions against the communist regime, both outside and inside Albania. Only after the fall of the communists in 1992 would it be possible for Albanians to decide by plebiscite on their constitutional regime, whether a Monarchy or a democratic Republic.

Mustafa Kruja’s Activity After 1939

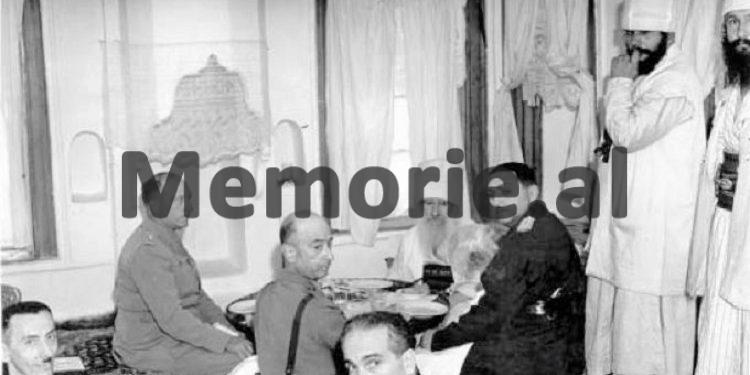

In the summer of 1941, seeing that the government of Shefqet Bej Verlaci was unable to control the growing internal unrest, particularly in newly occupied provinces like Kosovo, and the problems caused by the Italo-Greek War, the Italian Lieutenant [Mëkëmbësi] Francesco Jacomoni proposed Senator Mustafa Merlika Kruja to Mussolini and Galeazzo Ciano, Minister of Foreign Affairs, as the new Prime Minister of Albania.

According to his proposal, although Mustafa Kruja was of humble origins, he would successfully represent the country’s intellectual elite. For the Italians, Mustafa Merlika Kruja was the perfect man at the right moment. The anti-fascist resistance was still in an early stage, and for the Italians, the traditional government led by Verlaci had become a symbol of the inability to govern.

To the Italian Lieutenant Jacomoni, Mustafa Kruja appeared as a fervent nationalist. As such, he would serve the Italians well by presenting himself to the Albanians as an anti-communist, an intellectual, and, of course, a nationalist. Nationalism, which Mustafa Kruja embodied perfectly throughout his life, realized a cherished dream during the occupation, especially after 1941, with the creation of “Greater Albania” following its union with most of Kosovo.

After this union, the Albanian national question, according to the Italians, would be resolved, because it would be impossible for Albanians to rise against a prime minister who identified himself as a nationalist. This implied that they would not oppose the Italianization of Albania nor join the Anti-fascist Movement.

According to Pearson, Mustafa Kruja was appointed Prime Minister by the Italians to draw Albanians toward fascist policy, playing on their nationalist feelings through clever propaganda, while suppressing any attempt at resistance.

Mustafa Kruja’s government was thus the first national cabinet of Greater Albania. Kruja’s nationalist sentiments were openly displayed when he protested the statements of Anthony Eden, Cordell Hull, and Molotov regarding Albania in December 1942. For a long time, the Allies had been silent about Albania. It was the United States, which had never recognized the annexation of Albania by the Italian Crown of Savoy that broke this silence.

On December 10, 1942, Secretary of State Cordell Hull declared that, based on the Atlantic Charter, the USA desired to see a free, self-governing Albania with sovereign rights. Mustafa Kruja reacted immediately. In his speech to the Fascist Grand Corporate Council on December 23, 1942, he criticized each of these declarations, stating that they threatened Albanian national unity (tansia kombëtare).

The British declaration regarding Albania’s future borders after the war was the most concerning, as it would open border issues with Greece and Yugoslavia. According to Mustafa Kruja, this danger was proven by the Greek government’s approval of Eden’s stance, which demonstrated that after the war, Britain would support Albania’s neighbors and reduce its territory to a ghost state.

However, Mustafa Kruja failed to realize his country’s nationalist aspirations. His simple political program revealed his great political dependence on the Italians, as all decisions were subject to the approval of the Italian Lieutenant. He had limited successes. Although he tried to maintain contact with nationalists who opposed him, he failed to hold his position against the left-wing anti-fascists.

In this charged political state, Mustafa Kruja failed to take measures against anti-fascist resistance groups, especially the communists. The relative stability of the first phase of the Italian annexation did not last long, mainly due to the lack of administrative efficiency, the failed military campaigns of the Italians against Greece, the deteriorating economic situation, and the growing strength of the anti-fascist resistance.

In January 1943, Mustafa Kruja expressed his desire to withdraw from active political life. He never collaborated with the Germans, who generally avoided involvement with the traditional Albanian political elite, especially the Italophiles. However, he participated in several meetings organized by nationalist and monarchist circles, as a devoted anti-communist who still held some influence among them.

In September 1944, Kruja traveled alone to Vienna, where one of his sons was seriously ill. His son died in November 1944, just days before the German withdrawal from Albania. From that time until his death in 1958, Mustafa Kruja remained in exile, leaving his family, his wife, and his sons in Albania.

Fascism vs. Communism

Two reasons can explain Mustafa Merlika Kruja’s collaboration with Fascism during World War II. First, he was a declared nationalist who was willing to make a pact with the Axis powers to promote the Albanian nationalist cause.

The Italian Fascists identified Mustafa Kruja with extremist nationalism but also saw him as useful to Italian interests to pacify the anti-fascist resistance. Italy’s policy toward Albania best explains why he believed Italy was the only country with which Albania could collaborate.

Among the Axis powers, Italy, according to him, was the main supporter of Albanian national aspirations and the guarantor of its independence and national integrity. Hubert Neuwirth also mentions Mustafa Kruja’s hostility toward King Zog I as one of the reasons for his collaboration. In 1939, after the King went into exile, Mustafa Kruja returned to Albania from France.

He accepted the Italian proposal to become Prime Minister after Italy agreed to make several concessions regarding Albanian autonomy and to remove the fascist symbols of the House of Savoy from the Albanian flag, which had caused public discontent.

Mustafa Kruja enthusiastically welcomed the union of most of Kosovo with Albania and the creation of Greater Albania. Furthermore, he rejected and criticized the Allied declarations of 1942 that favored Greek and Yugoslav territorial claims against Albanian territory after the end of the war. His goal was to protect the achieved unification of Albania at all costs. Thus, in the name of the country’s national cause, Mustafa Kruja continued his collaboration with the Axis powers.

Secondly, Kruja was a fervent anti-communist. As he wrote himself, one of the reasons he agreed to become Prime Minister and collaborated with Fascist Italy was his opposition to communism, which he firmly believed would hinder Albania’s freedom. After the political activation of the left-wing resistance and the founding of the Albanian Communist Party by Yugoslav commissars, he accepted the Lieutenant’s proposal to become the “Quisling Prime Minister of Albania”!

According to Julian Amery, Mustafa Kruja continued the struggle against the communists, not only during his mandate as Prime Minister but also after his resignation. Amery argues that the British at that time were concerned about Abaz Kupi’s relations with the collaborators. However, Amery adds that in a country like Albania, the internal struggle between nationalists and communists, with the help of the “enemy’s friends,” was a form of objective collaboration. / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue