By Agron Alibali

Part One

Instead of an Introduction

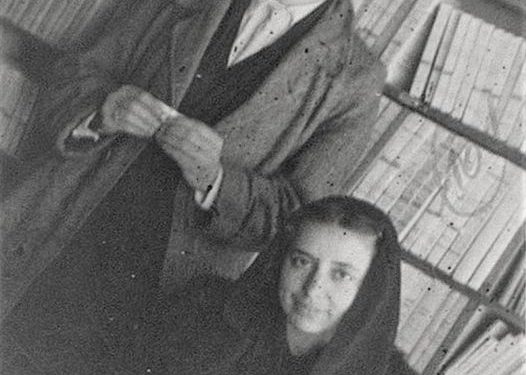

Memorie.al / The image of her in the courtroom remained in my mind – graceful, elegant, with long chestnut hair flowing over her shoulders. Taken during tragic moments, the photo radiated courage, defiance, determination, wisdom, and intelligence! I had also heard about Musine Kokalari [1917 – 1983] from my father, who had known her in Tirana, I believe at the “Lumo Skëndo” bookstore, one of the intellectual centers of the time. I had just passed through a period of ordeal in the villages of Gjirokastra where, in collision with the dictatorship, I found myself immersed in the realm of that culture, tradition, and language of our precious South, when in Tirana, I came across the charming volume “As My Old Grandmother Tells Me” (Siç më thotë Nënua Plakë).

I encountered the book in my grandfather’s rich library, who had surprisingly bought three copies. I devoured and re-read it several times, immersing myself in the strange world of mythical Gjirokastra, where Musine accompanied you with gentleness and elegance, through her gilded, fresh, and clear language and style – into the world where Kadare would later unfold his literary masterpieces.

Meeting in the Afterlife

The sentencing of a woman, her internment, the solitude imposed by the dictatorship, the end of Musine Kokalari in Mirdita – all of these conveyed only pain, along with the question “why?” The re-encounter with Musine occurred through a document from the archives of the U.S. Department of State. Like in a tragic black-and-white film conceived in text, Kokalari reappeared for posterity, ever defiant, graceful, with flowing chestnut hair, but now transformed into an object of violence.

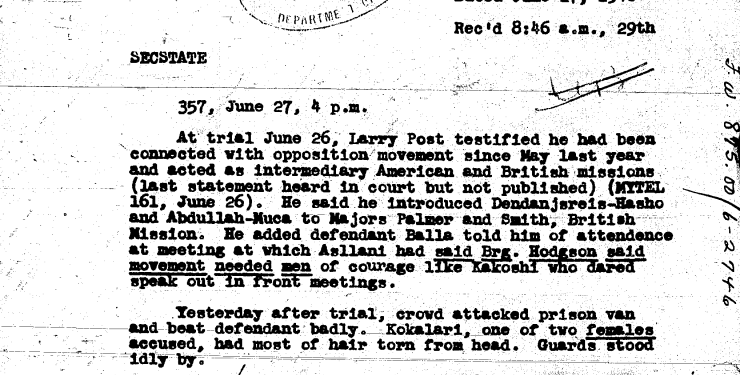

On the afternoon of June 27, 1946, a telegram arrived in Washington from the American Legation in Tirana. The author was the head of mission, Jacobs. The document is only one page long. The subject was the court session of the previous day in Tirana. The American and British missions were concerned about the mention of their connections with the accused. The text at the end becomes bone-chilling:

“Yesterday, after the court session, the crowd attacked the prisoners’ van and severely beat the defendant. Kokalari, one of the two accused women, had most of her hair torn out. The guards just watched…”!

Signed, JACOBS

Difficult Circumstances

The world had just emerged from World War II. It was the threshold of the Cold War. Albania was at a crossroads. The communists had no intention of relinquishing power. Alongside their orientation toward Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, they also sought to establish diplomatic relations with the USA and Great Britain.

This step would increase the regime’s legitimacy, but perhaps it was also a kind of original approach to “neutrality,” an inherent principle since the inception of the Albanian state.

The American diplomatic mission was tasked with observing developments in the country and recommending recognition or non-recognition. However, the British mission in Tirana did not yet have formal diplomats. The interests of Her Majesty’s government were represented by the British Military Mission [BMM].

The lack of democratic credentials of the Tirana communists, the campaign of terror, and the purges were serious reasons for non-recognition. However, the USA was actually closer to diplomatic recognition, where the main condition was the continuity of bilateral treaties concluded with the Albania of King Zog.

With the British, the situation was much more complicated. Albanian communists viewed every step coming from London or its representatives in Tirana with suspicion. Relations with them were burdened by political and emotional baggage that could not be ignored. Mistrust had been born during the war years in the mountains, when, even on a personal level, a certain disdain toward the locals was not infrequently observed in the behavior of the British.

The Resistance

The murder of the writer’s two brothers, Muntaz and Vesim Kokalari, on November 12, 1944, on the eve of the liberation of Tirana, was one of the harshest blows in her life. The Kokalari brothers were not armed and posed no threat to the combatants. The pure terrorist crime, consumed “in the heat of war,” was essentially an act of cowardice.

By the proposal of Musine, it was agreed to compile a Note or Memorandum, which would be sent to the Allies. Musine’s stance had prevailed: support was requested to postpone the elections and enable the participation of other parties. The Note was drafted and written by Musine with her own hand. Copies were delivered to the British and American missions.

The Trial

The writer was finally arrested on January 23, 1946. One by one, 36 other people were also arrested. The trial against the 37 accused of the “Democratic Union” organization began on June 18, 1946. The charge was a conspiracy to overthrow the government, sabotage, espionage, and the preparation of assassinations against the country’s leaders.

According to Musine, the essence or origin of the accusation was the Note drafted by her. She would declare in court: “There are thirty-six people accused here in this trial. Four groups, three of which have only one thing in common – A Note sent to the Allies to postpone the elections so that a democratic coalition could participate in them. There was no intention to overthrow the government. It was simply to have democratic elections.”

Musine’s stance during the investigation and in court was heroic. “I am for democratic culture. I am a disciple of Sami Frashëri. I am not a communist,” she stated during the interrogation. Musine defended herself but was not allowed to finish her speech, an act unacceptable by any standard and quite unprecedented. In the end, she did not ask for mercy, but only for justice.

The Seventy-Year Mystery?

This enigma tormented Musine for her entire life. She never managed to uncover the mystery of the great silence of the Great Allies during that summer and autumn of 1945. However, from the perspective of today, we are aided by a declassified document from the American archives, a telegram from Jacobs sent to the Secretary of State. / Memorie.al