By Volodimir Birchak and Volodimir Viatrovych

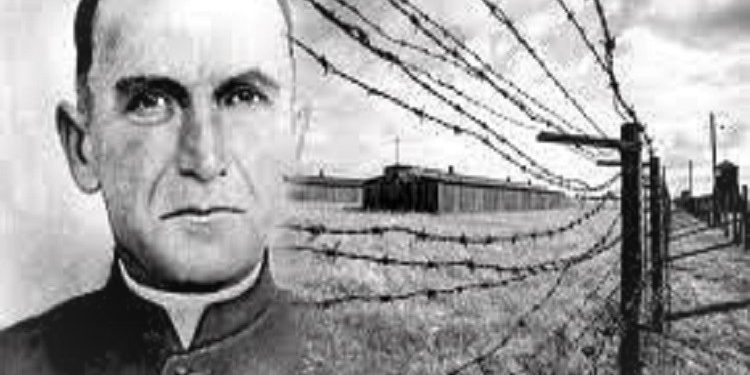

Memorie.al/“He was the son of a priest of one nation and died in the lands of another nation because he had saved the sons and daughters of a third.”

These words by Cardinal Lubomyr Husar represent the life story of Omelyan Kovch, who was a fervent patriot of his country, yet managed to rise above national prejudices. His birthplace was the land of Galicia, where Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews lived together for centuries.

The pages of the history of their coexistence are marked by many dramatic events and conflicts. But the figure of Omelyan Kovch symbol4izes a man who stood up for all representatives of these three nations.

On August 20, 1884, in the family of the Greek Catholic priest Grygorij Kovch, a boy named Omelyan was born; everyone knew his destiny. It was certain the infant would become a priest, like his father, his uncle, and his grandfather. Like every Greek Catholic priest in Galicia at the end of the 19th and 20th centuries, he would combine clerical service with active public work in rural areas. After all, this was the lifestyle of his grandfather, father, uncle, and hundreds of other priests of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, who became key figures in the Ukrainian national revival in Galicia, which at that time were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Almost all of these predictions proved accurate. But in addition to the expected clerical and public activities, the boy had to endure sufferings that no one could have imagined – two world wars, participation in the Ukrainian liberation movement, and persecution by Polish, Soviet, and Nazi powers, and death in the Majdanek extermination camp.

There were three other children in the family. But despite financial difficulties, Grygorij Kovch did everything possible to ensure that his son received a good education. After completing primary school in Kosmach, where his father was a parish priest, Omelyan continued his studies at the gymnasium (high school) in Lviv, the main city in Galicia, and then went even further from home – to Rome, where from 1905–1911 he was a student at the Saints Sergius and Bacchus College.

Studying in the Eternal City

The young man found an opportunity to live and study in the ‘Eternal City’ thanks to the help provided by the Head of the Greek Catholic Church at that time, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky. Years later, the Head of the Church would make another effort to help Omelyan Kovch; that would be the time to save him from death, not from poverty.

Before graduation and receiving holy orders, Omelyan Kovch married Marie-Anne Dobriansky, who was also the daughter of a priest. The happy family had six children – three sons and three daughters. The first parish where the young priest was assigned was far from home, at the other end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the town of Kozarats (modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina). His parishioners were poor Ukrainian immigrants, and for this reason, the priest’s family lived in difficult conditions.

But very soon, turbulent historical events changed the quiet life of Omelyan Kovch. In 1914, when World War I began, the priest returned to his birthplace, which became one of the arenas of the bloody war. Galicia was occupied by the Russian army, and then reoccupied by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and then the Russians returned.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy for Ukrainians at that time was the fact that, in the war happening on their lands, they were fighting against each other for foreign interests within imperial armies. This was the ‘price’ they paid for the lack of their own country.

Ukrainians learned this lesson. They rose to fight for independence. In the final phase of World War I, empires collapsed, and the states of previously oppressed nations began to emerge from their ruins. In November 1918, the West Ukrainian People’s Republic was proclaimed in Lviv. However, representatives of another people who previously made up the Austro-Hungarian Empire – namely, the Poles – also claimed ownership of Galicia. Thus began a war between Ukrainians and Poles.

In the Army

Among those who joined the Ukrainian Galician Army (UGA) defending the newly created West Ukrainian People’s Republic was Omelyan’s brother, Yevstahiy. Omelyan Kovch, being a cleric, did not have the right to take up arms, but he could not ignore his patriotic impulse and became a chaplain for the Ukrainian army.

Other priests performing their duties among UGA soldiers included Omelyan’s father, Grygorij Kovch. The elderly priest died of typhus in the army at the end of 1919. His son continued his service in the army until the final days. After being defeated by the Poles in Galicia, the army retreated to the east and defended the Ukrainian People’s Republic in the war against the Bolsheviks.

During the war, when people could witness the extreme faith and courage of Omelyan Kovch, he was often seen with soldiers at the advanced front. “I know,” he said, “that the soldier on the front line feels better when he sees a doctor and a confessor nearby.” And he jokingly added: “You know that I am consecrated, and a consecrated person is not an easy target for a bullet.” This faith allowed him to emerge from very complicated situations and inspire confidence in others.

He was eventually captured by the Bolsheviks, along with other UGA soldiers. The prisoners were loaded into wagons taking them to the place of execution. At one of the stops, the train guard, a Russian soldier, said, “let the pastor go,” telling him: “Father, do not forget to pray for Luka.” But instead of freedom, Omelyan Kovch found himself again in a camp for prisoners of war, this time a Polish camp. Typhus was the worst calamity; it took the lives of hundreds of soldiers every day. Father Omelyan stayed with those who were dying. However, he managed to survive and, after a long struggle, he returned home.

Between the Wars

In 1922, he took a parish in the town of Peremishlyany in the Lviv region. After the war, this territory belonged to the new Poland. Peremishlyany, like other towns of this type in Galicia, was multinational; in addition to Ukrainians, there lived Poles, Jews, Roma, and even some German families. Despite the recent war and the complicated history of relations between nations, the town’s population lived quite peacefully, trying to tolerate and respect the traditions and customs of other peoples. When Christians had an important religious holiday, Jews closed their shops and declared a day off, and Christians did the same on Jewish holidays.

Omelyan Kovch lived and worked in Peremishlyany during the short period of peace between the two world wars. Of course, he did not limit himself only to church work but also took an active part in the public life of the town. He was the founder of the People’s House (a place for Ukrainian national holidays) and the reading room of the “Prosvita Association,” whose goal was to raise Ukrainian national awareness. He also initiated the creation of the Ukrainian Bank, which was intended to be a tool for ensuring the financial independence of the Ukrainian community.

Kovch’s activities caused repressions from the Polish government, which sought to limit the development of the Ukrainian national movement, seeing it as a threat to the integrity of the state. Searches of the priest’s home became an unfortunate local tradition; from 1925–1934, there were about 40 of them. After these searches, he was arrested and imprisoned several times, for longer or shorter periods. Despite the persecution, Father Kovch was always open to everyone. He found time for his believers, but also for others – very often, Poles and Jews asked him for advice.

Soviet Oppressions

In September 1939, after the start of World War II and the establishment of Soviet power in Galicia, the situation in the town changed rapidly. The Poles, who enjoyed privileges as representatives of the power, were the first victims of communist repressions. Arrests and repressions primarily affected those who had been public servants and later moved to leaders of political parties and public associations. Father Omelyan was among the first to rush to help. With food, money, or just a kind word, he visited the families of Polish officers sent to Siberia. Their wives asked the priest – “How can you help us, when only a short time ago my husband conducted searches in your house?” But he only smiled and said that it was his duty.

In the first months of the Soviet regime, Ukrainians and Jews felt a sense of relief (communist propaganda spoke of their “liberation from Polish oppression”). But very soon they also became subject to persecution by the NKVD (otherwise known as the KGB). After the trains took the Poles to the East, wagons filled with Ukrainians and Jews also began their journey.

The Ukrainian national movement was declared “bourgeois nationalist” and hostile to the new government; its activists were arrested and sentenced to imprisonment or even execution. Omelyan Kovch escaped oppression during that terrible time. He continued with his clerical service; furthermore, he dared to organize mass religious events for the faithful, despite the government’s emphasis on anti-religion.

In 1941, oppressions by the new government constantly increased. The prisons of Western Ukraine (at that time annexed to the USSR) were filled with prisoners, mainly political ones – those whom the government called “enemies of the nation.” Most of them were young men and women, activists of the “Ukrainian Nationalists” organization, who had launched an underground anti-Soviet struggle.

On June 22, 1941, a new phase of World War II began with German troop attacks against the Soviet Union. The Soviet government proved to be unprepared for such rapid events and was unable to organize an effective defense. The Germans advanced further east with every passing hour. Meanwhile, the Soviet political police force – the NKVD – was busy arresting all “politically unreliable” individuals.

That day, Father Omelyan Kovch was to be among them. Some citizens (some witnesses say they were Jews) hid the priest, and thus he escaped not only arrest but perhaps execution. The Soviet government left a trail of blood across all of Western Ukraine – after its retreat, the bodies of thousands of people were found in prisons. They had been shot without any trial, as there was no time for hearings and no means to evacuate the prisoners. Among those executed were many priests.

Meanwhile, it was already the fifth change of power that Omelyan Kovch had observed in his homeland. The Nazis would not restore any state there; neither Polish nor Ukrainian. The territory was to be only a colony of the Third Reich and its population slaves for the new rulers; the German authorities treated Ukrainians and Poles with contempt and deprived them of many rights. But their attitude toward the Jewish population was worse. Mass killings began from the first days of this new power.

Uncompromising Faith

Scared by constant oppressions, people often tried to ignore the atrocities committed against others. Everyone was preoccupied with their own problems and left alone with their pain and fear. This fear was also accompanied by various national prejudices and memories of past problems and conflicts. All of this allowed people, in a way, to forget the suffering of others and ignore the extermination of other nationalities.

But Omelyan Kovch never compromised his moral values even in such a time, regardless of how much it might cost him. And again, his faith and certainty worked miracles.

In September 1941, a group of German ‘SS’ closed the synagogue in the town of Peremishlany, filled with people who had come to pray at that very time. Someone threw bombs inside. A fire started; people rushed to the door and realized they were caught in a deadly trap. “A Roman Catholic priest and a group of people ran to Father Kovch, asking him to help save the synagogue,” former Peremishlyany resident Leopold Klyajman-Kozlovsky recalls: “Kovch, who spoke German perfectly, shouted at the German soldiers, asking them to let him into the synagogue.” The soldiers were stunned by the surprise and let him enter. Kovch rushed to pull the people out of the burning synagogue.

Aaron Roqueah, the Rabbi of Belz, was among those Father Kovch saved.

Omelyan Kovch was capable not only of a single heroic deed but also of long-term dangerous work. When a ghetto was created in Peremishlyany, the priest entered on more than one occasion to help the Jews. He brought them food, medicine, clean clothes, etc. Another way the priest managed to save Jews from extermination was through so-called “Aryan documents” (information taken from church baptismal books). It was Rubin and Itka Piza who managed to survive thanks to documents provided by Omelyan Kovch.

For such activity, Father Kovch was arrested by the Gestapo in January 1943 and imprisoned in Lviv, in the prison on Lontskyy Street. His family, friends, and even the Metropolitan Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Andrey Sheptytsky, did everything to free him. The Nazis set a single condition for his release: the Ukrainian priest must submit a written pledge not to help Jews. Father Omelyan refused. “Listen to me, Mr. Stavitsky,” he told a Gestapo officer, “you are a police officer. Your duty is to look for criminals outside. Please leave God’s matters in God’s hands.” The officer, indignant at the priest’s response, ordered him back to prison.

The Majdanek Concentration Camp

This time he was tortured for a long time in prison and then sent to the concentration camp, Majdanek. But even being in the terrible death ‘factory’ did not break the pastor. “I understand that you are making efforts to free me,” he wrote to his family, “but I ask you to do nothing. They shot 50 people yesterday; if I am not here, who will help them go to the other world? They will continue forever with their sins, in deep despair hanging over this hell. But now they are leaving with their heads held high, with sins far behind. They cross the bridge with joy in their hearts, and I see peace and quiet take place in them when I talk to them for the last time.” Omelyan Kovch believed that there, among people condemned to death, he would fulfill his mission in the most appropriate way. And this was the most important thing for him.

“I am grateful to God for being so kind to me,” we can read in one of his letters. “But for that heaven, this is the only place where I would want to be. Here we are all equal. Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Russians, Lithuanians, or Estonians. I am the only priest here. I cannot imagine what they would do without me. Here, I can see God – there is only one God for everyone, regardless of our religious differences. Perhaps our churches are different, but they are all dominated by Almighty God.

When I serve the liturgy, they are praying. They pray in different languages, but God understands all languages, right? They die in different ways and I help them cross the bridge. Isn’t this a blessing? Isn’t it the best crown God could ever place on my head? This is true. I thank God thousands of times a day for sending me here. I could not have asked for more. Do not despair on my account. Rejoice with me. Pray for those who created this camp and this system.”

Omelyan Kovch, prisoner No. 2399 of Majdanek, worked like everyone else in the camp, but after hard physical labor, he served as the priest of a terrible death factory. He gave comfort to all those in need, regardless of their nationality or religion. The brutal conditions of the camp finally broke the health of the priest, who was no longer young. He died behind the barbed wire on March 25, 1944, only a few months before the liberation of Majdanek.

The official reason for his death was ‘heart weaknesses. The body of the priest, like thousands of others, was burned in one of the camp’s terrible crematoriums. But the memory of this righteous man could not be destroyed as easily as his body. The people he saved remember him for his deed. In 2001, during a visit to Ukraine, Pope John Paul II declared Father Omelyan Kovch a ‘Blessed Martyr’.

Between the Wars: A Life of Service in Peremishlyany

In 1922, he was assigned a parish in the town of Peremishlyany, in the Lviv region. After the war, this territory became part of the new Poland. Peremishlyany, like other towns in Galicia at the time, was multi-ethnic; besides Ukrainians, there lived Poles, Jews, Roma, and even a few German families. Despite the recent war and the complicated history between these nations, the town’s population lived in relative peace, striving for tolerance and respect for each other’s customs. When Christians celebrated a major religious holiday, Jewish merchants closed their shops to honor the day, and Christians reciprocated during Jewish holidays.

Omelyan Kovch lived and worked in Peremishlyany during this brief interlude of peace between the two World Wars. He did not limit himself to church duties but was deeply involved in public life. He founded the “People’s House” for Ukrainian national celebrations, established a reading room for the “Prosvita Association” to educate the populace, and initiated the creation of the Ukrainian Bank to foster the community’s financial independence.

These activities drew repression from the Polish government, which viewed the Ukrainian national movement as a threat to state integrity. Searches of the priest’s home became a frequent and unfortunate occurrence; between 1925 and 1934, his home was raided about 40 times. He was arrested and imprisoned repeatedly. Despite this, Father Kovch remained open to everyone; even Poles and Jews frequently sought his counsel and wisdom.

Soviet Oppressions and the “Red” Terror

In September 1939, with the onset of WWII and the arrival of Soviet power in Galicia, the situation shifted rapidly. The Poles, previously the ruling class, became the first victims of Communist repression. Arrests targeted former public servants and political leaders. Father Omelyan was among the first to offer aid. He visited the families of Polish officers deported to Siberia, providing food, money, and comfort. When their wives asked, “How can you help us when our husbands were the ones searching your home not long ago?”, he simply smiled and replied that it was his duty.

Initially, Ukrainians and Jews felt a brief relief under the guise of “liberation from Polish oppression,” but they soon fell victim to the NKVD (later known as the KGB). Trains filled with Poles heading east were soon followed by wagons packed with Ukrainians and Jews. The Ukrainian national movement was branded “bourgeois nationalist” and hostile; its activists were imprisoned or executed. Omelyan Kovch managed to escape arrest during this dark period, continuing his ministry and even organizing mass religious events in defiance of the fiercely anti-religious regime.

By 1941, Soviet oppression intensified. Prisons in Western Ukraine were filled with “enemies of the nation,” mostly young activists of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. On June 22, 1941, as Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the retreating NKVD carried out mass executions of prisoners in Western Ukrainian jails. Father Omelyan was saved from this fate by citizens (including Jews) who hid him, preventing his arrest and near-certain execution.

Uncompromising Faith: Defying the Nazis

The arrival of the Nazis brought a fifth change of power. The Third Reich viewed the territory as a colony and its people as slaves. Mass killings of Jews began almost immediately. While many were paralyzed by fear or historical prejudices, Omelyan Kovch never compromised his moral values.

In September 1941, a group of SS soldiers locked a crowded synagogue in Peremishlyany and set it on fire with bombs. Hearing of this, Father Kovch – who spoke perfect German – rushed to the scene. He shouted at the soldiers to let him inside. Stunned by his boldness, they stood aside. Kovch rushed into the burning building and dragged people out of the death trap. Among those he saved was Aaron Roqueah, the Rabbi of Belz.

Kovch continued his dangerous work, entering the ghetto to bring food and medicine to Jews. He saved many from certain death by providing them with “Aryan documents” – baptismal certificates extracted from church records. Rubin and Itka Piza were among those who survived because of his bravery.

For these actions, the Gestapo arrested him in January 1943. He was imprisoned in Lviv. Nazi authorities offered him a single condition for release: he must sign a written pledge to stop helping Jews. Father Omelyan refused, telling the Gestapo officer: “You are a police officer; your duty is to catch criminals. Please leave God’s matters in God’s hands.” Enraged, the officer ordered him back to his cell.

The Concentration Camp at Majdanek: The Final Mission

After enduring torture, he was sent to the Majdanek concentration camp. Even in this “death factory,” his spirit remained unbroken. He wrote to his family, pleading with them not to seek his release:

“I understand you are trying to free me, but I ask you to do nothing. Yesterday they shot 50 people; if I am not here, who will help them transition to the next world? … Here, I see God – there is only one God for everyone, regardless of our religious differences. I thank God thousands of times a day for sending me here. I could not have asked for more.”

Omelyan Kovch, prisoner No. 2399, worked hard physical labor by day and served as the “Parish Priest of Majdanek” by night. He provided confession and last rites to Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Russians, and Estonians alike. The brutal conditions finally exhausted his health. He died behind the barbed wire on March 25, 1944, just months before the camp’s liberation.

The official cause of death was “heart weakness.” His body was cremated in the camp’s ovens. However, his memory endured. In 2001, during his visit to Ukraine, Pope John Paul II declared Father Omelyan Kovch a “Blessed Martyr,” a man of God who stood as a beacon of humanity in an age of darkness./Memorie.al