Memorie.al / The poet left behind very little poetry – only one book of less than two hundred pages in total. However, this breed of artists has never been known for quantity. Add to this the fact that for Fredi, the green light opened late, by which time he had become indifferent to things like success.

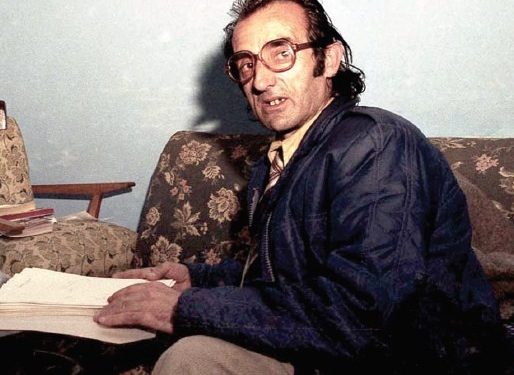

Today, I leafed through the books of Frederik Reshpja, a poet from Shkodra whom I read from time to time, yet never close his books with the feeling that I am “done” reading him. I own seven of his books. The first, Albanian Rhapsody, was published in 1968 when the poet was twenty-eight. Then came the novel The Distant Voice of the Hut (1972), followed a year later by his second poetic volume, In This City (1973).

Then followed a long silence, until 1994, when he reappeared with The Hour Has Come to Die Again. Two years later, he published Selected Lyrics, and in 2004, two editions appeared back-to-back: Solitude and In Solitude. On February 17, 2006, he passed away. Friends who loved him and stayed by his side describe him as a noble yet difficult man.

And it is believable. He belonged to those called “born poets.” There is no other poet in the Albanian language that fits this definition more convincingly. He was a poet of the lineage of William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, Sergei Yesenin – a breed somewhat lacking in our culture.

I was once horrified to hear an Albanian writer – who also claimed to be a poet and held academic rank – say: “I could have written like the French Symbolists (Rimbaud, Verlaine, Mallarmé), but our readers wouldn’t understand me!” In fact, Frederik’s first book was perfectly crafted according to the requirements of its time.

It was the mid-1960s. The Communist state was refining its ambitions to control and suppress free thought, even the very nature of freedom, to turn the individual into a mass. Under these external conditions, and while internal creative energy sought ground, the poet made concessions in his themes. Artistically, he was searching for himself – his inner voice – within that forest of difficulties, leaning toward high tones and the epic nature of things.

His second book of poems, In This City, was a significant leap in quality. The voice softened and took on interesting, sometimes Whitmanesque hues. It is well known that art at that time was required to affirm happiness – a feeling which, as Valéry says, “is not inclined to turn into words because it is an end in itself.”

But the poet managed to master an alchemy through which he processed his material. Even though this material was generally imposed, he achieved genuine artistic effects. For him, sincerity was not as important as creation. “Anila, happy bird flying over the roofs of days / Your youth came like great news knocking at the gate,” he writes in the poem Letter to Anila.

He had faith and conviction in only one thing: poetry. He was not dependent on any political side, any school of art, any “white” friend, or any “black” friend. He was an unbound soul and, as such, he prized freedom. That was it. “I spend time with people only out of politeness,” he would say in an interview. Once, he traveled from Shkodra to Tirana, and at the Writers’ Union, hosts asked him about a fellow writer and friend: “What does X say?” His answer was: “He’s a poor soul, but he has no talent.”

The second book was written during the brief period of “liberalism” in the early ’70s. Shortly after, it would have been deemed unsuitable due to its equivocations, ambiguities, and mysteries that baffled the system. Here is a sign of modernity, an overlap of metaphors from that book: “I hear the wind blowing through my words, which suddenly turned green.”

This book contains much light, color, and hope. It includes the beautiful ballad Kata. At the time, the author was just over thirty. If we compared the poet’s life to an astronomical day, this period would be “the day,” while the post-90s years would be his “evening or perhaps even his “night.” The poems of this later period are filled with shadow and sadness, with little light or optimism.

It seems as if even pain is gone, leaving only ash. In fact, this can only be said in a physical sense, because in his poetry, the poet’s alchemy has become magic itself. What was lost over the years was artificiality; even literary artifice became raw material.

We are left only with poetry: intense aesthetic emotions, images transposed from one verse to another, irony, paradoxes. The appearance of this definitive poetry in Albanian literary life immediately after the fall of the dictatorship remains a mystery. His earlier poetry often took the form of a diary – encounters and experiences with people and places. It had chronicle and geography.

This type of poetry communicates easily with the public. Now, the themes have almost vanished. What remains is the unchangeable substance of the soul – an essential matter that takes shape through the movements and fixations of an unconditioned imagination.

The entire astronomical space has been transposed into spiritual space. The perception of the world is no longer through empirical experience, but through intuitive flashes. In the ’70s, he wrote a poem for Anila to make something beautiful and acceptable; in the second period, things changed. Now, even when he writes about his own pain, he doesn’t do it to inform others. He actually pretends, as Pessoa says, to feel the pain he actually feels.

He writes poetry not to realize him – as that would remain forever unfulfilled – but merely to remember an old passion. Yet, this care for memory is his very existential being. Now past fifty, he recalls that he once wasn’t afraid of long genres: novels, long poems. Now, in an interview, he recalls Éluard saying: “But let us ask if he fought before the world defeated him.”

Indeed, our poet fought by following his nature. His imagination, unified with his being, functions beautifully in secret, undiscovered corners. Things no longer have one meaning, one sound, one color. According to William Blake, those are matters of reason, not poetry. Reshpja’s poetry becomes polyphonic and multicolored. It is the existence of things that do not exist.

Reading it becomes part of the creation itself. No one knew these things as well as Frederik. However, this makes the poetry elite – reducing its communication with the general public, who find it easier to approach simple logic than the waving game of imagination. Yet, “Talent thinks, the artist sees,” Blake said. Frederik is a poet of visions and apparitions.

Rreshpja was not one of those artists who used art as a passport to a career elsewhere, nor one of those who give “genius to life, and talent to works.” In socialism – persecuted; in democracy – ignored (not necessarily through the fault of others). Incapable of settling into life, he created his work in conditions of misery and pain, full of spiritual wounds.

His brilliant poems, spare in words, rarely exceeding twenty lines, are always enclosed in an unassailable unity. They are not difficult to understand, but they are elite due to deep artistic refinement. They are not “popular,” yet this is a true sign of modernity.

I offer as an example, ‘Requiem’, from the book The Hour Has Come to Die Again (1994):

A dead autumn day floats in the stream

Wrapped in leaves,

And the last storks passed by frozen

With yellow eyes in silence.

The sadness of snow falls from the trees

The valley painted by the moon,

And the storks of the wind wail with pain

With horns of broken ice.

This autumn died for me too, passed like this day

The shroud with withered leaves,

O winter of the deer with horns in the wind

Which autumn shall we mourn first?

The “sin” of this poetry is that, being universal, its material does not lead us to a known geography or time where we can attach our empirical sentiments; yet it is rare in its execution, through a language that sings like music. As the German scholar Hans-Joachim Lanksch pointed out, unlike his life, Reshpja organized the chaos of his poetry perfectly.

He was part of the all-Albanian artistic elite. He always lived on the edge of society, though he lacked the vices for which “pure” society curses a man. His spiritual state was always in a state of lack, as he lived in the shadow of the God of Loss. This is the source of the strong coloring of his poetry, which never falls into decadence but maintains a noble nature.

Unfortunately, there aren’t enough signs that Frederik is read by students or sought after in school curricula. I feel this because I work in a library. It is late at night. From Mt. Dajti, where snow has fallen again, a cold wind whistles over the lights of Tirana.

“O winter of the deer with horns in the wind!” I whisper this line of Frederik’s. On my desk, I have his seven books. But today, we do not have a dignified, integral publication of the work he left behind. If you want one of his books, you cannot find it. Research and studies are needed for this national treasure.

Frederik Reshpja had a mission to fulfill, for which he fought and sacrificed, but he did not break. He left behind a work that is blessed and qualitatively dignified. / Memorie.al

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)