Part Two

Memorie.al / He had lived as a Pasha and an Ottoman governor of the Catholic faith. He had passed away far from the country he loved so much, and for which he had written one of the most beautiful poems, one that no compatriot would fail to know. Fate had reserved for Vaso Pasha, 86 years after his death, to return to his homeland in a “grave without a cross.” On the 100th anniversary of the League of Prizren, the communist regime in power, after many efforts and ordeals, would bring the “father of Albanianism” back to Shkodër, where he was born, reburying him in its own way. The two following accounts tell the adventure of the return of Vaso Pasha’s remains to the Homeland in the distant year of 1978. The protagonists of the accounts are an Albanian diplomat and a journalist from Lebanon. Dalan Buxheli told the story in an interview given many years later to an Albanian newspaper. Meanwhile, Melhem Mubarak himself wrote the history of the return of the remains in the Albanian Catholic Bulletin, which was published in the USA in the 1980s and ’90s.

Continued from the previous issue

THE SECOND ACCOUNT

The Return of Pashko Vasa’s Remains to Shkodër

Melhem M. Mobarak

The road from Beirut to Hazmieh passes through hills filled with lemons and oranges and other trees that fill the landscape with colors. This May 31, 1978, a formal ceremony is taking place in the Hazmieh cemetery, also known as the Pashas’ Cemetery.

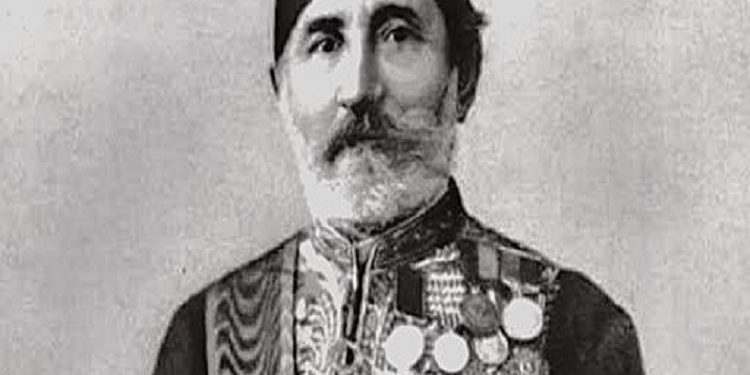

The Albanian Ambassador, Sulejman Tomcini, smiles: after 86 years of imposed exile, the body of Pashko Vasa Shkodrani along with that of his second wife, Katerine, and his daughter, Marie, will soon return to his birthplace. In 1883, this great Albanian patriot, the author of the militant poem “O My Albania” (Oh moj Shqypni), was appointed the fourth Governor of Lebanon, a post he held for ten years.

To guarantee the autonomy of Lebanon and its Christian citizens, the Seven Great Powers (the Ottoman Empire, France, England, Prussia, Austria, Russia, and Italy) had signed a special agreement stipulating that the Governor or “Mutesarrif” of Lebanon must be a Catholic Christian and of Ottoman nationality.

With complete knowledge of the Arabic language, the talented poet, intellectual, and polyglot Pashko Vasa served in this post until his death. His family life was also sad. Having lost his first wife shortly before his appointment to Lebanon, he married Katerine Bonatti, a young Greek woman.

This responsible lady took care of his only daughter from his first marriage. Unfortunately, three or four years later, Katerina died of cancer. This sorrow was followed by another very painful loss. In 1887, his beautiful daughter, Marie, also died.

Thanks to her father’s political reputation, Maria had married an Armenian financial magnate named Kouppelian. Through his clever moves, as well as unscrupulous financial methods and bribes, Kouppelian managed to institutionalize his little kingdom in Lebanon; all the while his father-in-law was in power.

The understandable situation of weakness and loneliness, following the death of his wife and daughter, caused Pashko Vasa to find consolation in his son-in-law and his two granddaughters, naturally giving them much paternal and grandfatherly love. Exploiting this weakness, Kouppelian, the Pasha’s son-in-law, extended the fraud and corruption throughout all levels of the administration.

Despite this failure, during the governance of Governor Pashko Vasa, Lebanon enjoyed peace, economic progress, and artistic development. Several large road networks and bridges were built. Many important government buildings and hospitals were constructed.

The Governor also built the State Printing House and encouraged archaeological excavations. Once, as a French newspaper wrote, he attended the ceremonies organized by the students of the Jesuit College on their graduation day.

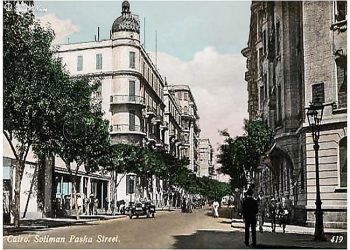

Very little known is the fact that Ismail Qemali, the father of Albanian independence, was appointed Vali (Governor) of Beirut in 1891. Pashko Vasa spent his winters in that city, and they certainly met often there.

At that time, at the insistence of his friend Monsignor Piavi, Pashko Vasa, to alleviate his loneliness, agreed to marry a young French woman who had been the governess of his two granddaughters. She bore him two sons, the eldest of whom was named Mikel.

In June 1892, Pashko Vasa died, a year before the end of his ten-year term as Governor of Lebanon. No one better than Ismail Qemali, with a somewhat strange account, described the last days of Pashko Vasa’s life.

Ismail Qemali’s Memoirs on Pashko Vasa

“During my stay in Beirut, my compatriot, Pashko Vasa, the Governor of Lebanon, died. He was suffering from heart problems, and his condition quickly worsened, leaving no room for hope.

Since the function of the Governor of Lebanon was important, and since there could be many local problems if that post remained vacant, I thought it best, after consulting with the doctor beforehand, to write to the Sublime Porte about these facts.

To my surprise, the Grand Vizier, instead of treating my communication as confidential, contacted Pashko Vasa, asking him about his health, and then informed me that he had received a response from the Governor, who had told him that he was improving!

One or two days later, he died. The Porte entrusted me with the temporary governorship of the province of Lebanon, under the direction of the Administrative Council. But since the Council consisted of the president and ten members, a conflict arose among them which effectively blocked all administrative decisions. I was asked to mediate, and then I reached a satisfactory formula for both parties.”

The funeral was held in the Chapel Church in Beirut and his body was placed in the religious cemetery in Hazmieh. This small village, under the Mediterranean sun and among the olive and cypress trees, which reminded one of the Albanian landscapes, was a resting place for him.

Time flowed on…

In 1967, the first attempts to return Pashko Vasa’s body to Albania were made by Dalan Buxheli (at that time the commercial attaché of Albania in Cairo). At that time, an administrative order, issued based on the “Vakëf” cemetery regulation in Hazmieh, blocked his request. Moreover, at that time, Lebanon did not have diplomatic relations with Albania.

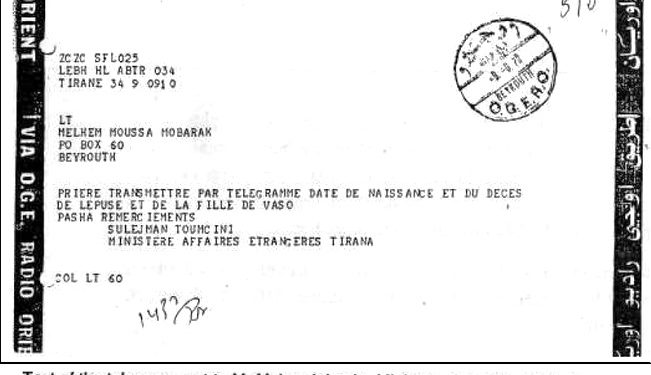

In 1978, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the League of Prizren, the Albanian government decides to address the Lebanese authorities once again, with a request to return the remains of Vaso Pasha to his Homeland. During my first visit to Albania, in March 1978, two professors, Aleks Buda and Vehbi Bala, asked me if I could help in this matter.

After my return to Lebanon, I met with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Fouad Boutros. He promised me that as soon as the official Albanian request arrived, he would take the necessary steps to shorten the bureaucracies and give a positive answer to the Albanian request. / Memorie.al