From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part fifty-four

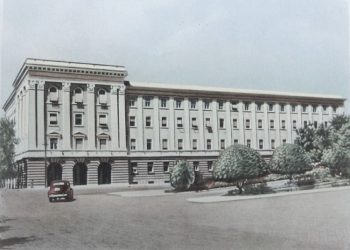

S P A Ç I

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My Memoirs and those of others)

Memorie.al / Now in old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whom the regime silenced and buried in the nameless pits? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, although I wholeheartedly tried to help my friends even slightly, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard those three days, I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

Now the balance of forces changed, the police gang narrowed the circle in a horseshoe shape, but Pali stood stoic, with the rod in his hand. It was then that I woke up. I glanced out the window, but a flock of people had occupied Ali Tromba’s sleeping spot, two beds away from me, and blocked my view. I asked them what they were staring at so intensely; had the poor unfortunate man jumped the wires, or had some depressive person thrown him from the height of the terrace?!

Since no one answered me, I went to the threshold, but the balcony was also black with dozens of people. I entered the swarm of people going up and down the third floor, watching curiously and tensely from the appeal square. When I turned that way, I found myself before an unimaginable scene, which I will strive to describe exactly as it was imprinted on me at that moment.

The above I have from the mouth of friends present at the scene, below is authentic, what I saw with my own eyes; the event is stamped on the celluloid of my memory, I don’t believe it will fade until death!

The crowd stood silently at a distance, but the number increased second by second. As the police rushed to close the matter, they split into two groups. The first, under the leadership of Fejzi Liçaj and Medi Noku, charged Pali; the others incited those present with shouts:

“Run to the dormitory or the mess hall and get ready for work!”

The pressure increased the tension and enraged the convicts, so much so that they no longer cared. “Disperse,” the police roared again, but no one obeyed. Meanwhile, near the clump of thorns, this dialogue unfolded:

“If you return to the cell voluntarily, there will be no consequences!” – lied Fejzi Liçaj.

“The first one who comes close will pay with his life!” – threatened Pali.

“I am warning you for the last time, surrender!” – yelled Fejziu.

“David” with a lever, facing “Goliath” with four heads – this apocalyptic scene was unfolding before our eyes. Who would be defeated? The square was full, others occupied the balconies and windows, their eyes fixed on the Spaç amphitheater, where some actors were playing the final act of the absurd theater, moving like marionettes.

We all supported Pali, but we chose silence. In a moment I lost my mind, Medi attacked Pali, but the lever threw him to the ground. At that moment, the spy’s scream echoed through the stream valley, and the people held their breath, even the policemen froze. Fejziu and the others rushed forward, but the rod whizzed, and their caps were knocked to the ground.

The police gang surrounded Pali, who was distracted or hit by blood, blocked his arms, and dragged him over inert materials to the end of the square, where the countless crowds wrestled him out of their hands. Accustomed for thirty years to freely using violence without encountering opposition, because even in a sporadic case, they had responded in a group, savagely punishing anyone who dared to stand against them, the military men were frightened and intimidated.

It seems this time the cup of patience was full, and the human barricade led by Jorgo Papa, Dash Kazazi, Pavllo Popa, Muharrem Dyli, Hasan Llibo, Pandi Sterjo, Sulo Veshi, Rexhep Lazri, Fadil Dushku, Haxhi Bena, Dervish Sulo, and many others – whom, due to the chaos in the square and the crowd on the balcony where I was standing, I couldn’t register – clashed fiercely.

The cohort of freedom crushed the police squad and drove them away with their tails between their legs. To my knowledge, such a massive revolt was happening for the first time. During my prison years, I witnessed individual acts of defiance by one, two, or three people, just as I witnessed punishments of the same nature, but attempts at resistance were extinguished as soon as the police opposed them, and woe betide the wretch who fell into their hands; he would suffer terribly and would not forget it as long as he lived, if he remained alive.

This turmoil did not match any of the previous ones, either in content or form. The prisoners were intoxicated by the scent of freedom! They challenged the state and defeated the police, who had abused and killed them for thirty years. The older ones had told me about previous events, about individual fits of temper over trivial causes, such as opposition to some bully policeman who sought to satisfy his whims, or when someone attempted to escape through spontaneous confusion.

But this was motivated. They defended the life and dignity of a fellow sufferer who was being violated in front of others, due to the whims of a wicked operative and some ignorant policemen. They saw us as objects, working animals, or serial numbers that completed the sum total and justified the salaries they received, without ever thinking that we might revolt, much less resist in unison, because they were convinced that they would be in power forever and would enjoy the privileges stemming from the military uniform until retirement.

They considered themselves senators and us slaves, almost amorphous beings, with whom they could do whatever they wanted, sell us, buy us, even dismember us and satisfy their animal ego. The solidarity of the “slaves,” which rarely happens, deflated the swaggering bullies, puffed up like roosters, who took to their heels terrified and were not seen where they went. In Spaç Quarry, the unbelievable happened: the prisoners desecrated the state!

“Tarti,” the dog adopted by Fiqiri Muhaj and rose with us, stayed by Pali’s side and shook the legs and arms of every military uniform, tearing at every corner of cloth whenever it appeared. After nearly five minutes, the police lost their “glory” and retreated, beaten and scratched horribly, leaving behind their starred caps, which “Tarti” ripped to shreds with his teeth.

I cannot say exactly who raised their hand first, even though I was no further than twenty meters away. But the moment when Pavllo Popa shouted has stuck with me: “Shame, ‘Tarti’ shamed us men, and we stand by as onlookers while they violate our comrade!” Muharrem Dyli hit the policeman nearby, the comrades rushed the others, and the commotion broke out. One cannot be blind when they violate one’s kind, right before one’s eyes!

It often happened that they tied me to posts with hay wire, beat me with stakes, mutilated and bloodied me, laid me on the snow or mud and stepped on my back with kundra [clogs with studs] and goads, etc., but I was never as indignant as that day, when ten military men attacked a wretched, hungry, and exhausted man, after three months of isolation.

The same feeling was shared by all the fellow sufferers, who, without considering the consequences, rushed the police in revolt, saved their comrade from the claws of the executioners, and started the revolt. Due to the distance in time, I may have forgotten the names of many fellow sufferers or confused the details, because the event unfolded quickly and the melee did not last, but I will never erase from my memory Fejzi Liçaj and the policemen when they fled terrified, without their caps.

From whatever angle you look at the clash, it resembles a spontaneous revolt. Both the physical confrontation and the emotional outbursts came as a result of violence and hatred accumulated over decades.

The ignorant were accustomed to violating even the rules they had approved themselves and to exploit the political prisoners brutally: they mistreated them, underfed them, poorly clothed them, tied them to posts with hay wire, tortured them, and isolated them in cells even when they were sick. They kept them in the mines for two shifts even when the norm was not realized through their own fault; they cut off their correspondence, reduced meetings with family members, returned food packages, and erased the days off that the law granted them from the calendar. It was normal that it would explode one day, but they did not think it would originate from a trivial incident.

Nevertheless, world history knows a heap of similar cases, because every regime, however successful, has an end, especially communism, which was conceived on collective lies and produced collective disappointment. The visionaries of the political prisons foresaw the collapse, even though the leaders of the time did not see the end and had sworn to wash it with the blood of hundreds of martyrs.

That day, freedom challenged crime, cut the rope that the regime had stretched, and the crater of the underground volcano, which they thought was extinct, burst! A few minutes after the incident, Shahin Skura entered the camp, accompanied by a slouchy officer, who, as I learned, was the Head of Penal Enforcement, in the General Directorate of Prisons, Sulejman Manoku.

Strange! His presence within minutes, perhaps at the very moment the event occurred, was at the command post, or he may have intentionally come to stimulate it. Even today, forty-five years later, I cannot explain the mystery of that presence!

The two superiors tried to negotiate, but achieved little; besides their own inviolability and that of the policemen who were not part of the punishing escort, and the guarantee that the first shift would go to work, they could neither return Pal Zefi to his cell nor neutralize the ones who hit the policemen. The intervention seemed to restore some order, but the fragile calm could explode at any moment.

As the meal distribution finished, the first shift lined up at the entrance gate of the mines. The police did not insist as always on the part that did not show up for work, perhaps they were intimidated by the scale of the revolt, or the camp leaders instructed them to do so, or those above them. As the waters flowed, those above aimed for division, to intervene more easily, and to act supposedly in the name of the law.

The forenoon passed relatively quietly, except for our whispers and the presence of Sulejman Manoku and Shahin Skura, who lied about supposedly intervening to fix the mistakes; there were no spontaneous developments. The minimization of the police presence inside the camp contributed to the relative calm, because only one spark would be enough to bring back the morning situation, although outside, the movements of the military increased, as if something macabre was being prepared behind the scenes.

At two o’clock, the second shift was also sent to work, without any serious resistance, apart from the rage simmering inside and the few people who did not show up at the gate. On the tuff stairs, facing the ordinary camp, I stopped as usual and prepared to wait for the daily ironies: “We dug the grave for the enemies,” but the wretches across the way were frozen like never before; they did not even utter the ironic taunt: “May your remains be left in the mine!”

Strange, how did the ruffians suddenly change? That silence indicated that the echo had crossed the political fences and scratched the ears of the ordinary prisoners, or the “crutches of the regime,” as Doctor Astrit Delvina mocked them.

This ambiguity erased the mystery; from now on, the news would spread to everyone and break the regime’s deafness, cross the borders, and people would learn about the act of communist tragedy that was being played out in Spaç; perhaps even the responsible institutions would react.

Thus, the echo of freedom spread far and wide!

“Why are you frozen like a wax soldier, friend!” – mocked Doctor Astrit.

While Mërkur Babameto was silent as a fish, on the uphill path of the ordeal. I didn’t speak until the turn of the first zone, where I addressed Astrit:

“Doctor, what do you think about the morning event?” When I expected an answer, Mërkur intervened:

“Boy, how many months of prison do you have left?”

“Two months and some, if I am lucky enough to have that fate!” – I replied pessimistically.

“Look out for yourself; these are not matters for you!” – And he left towards the carbide depot.

“You didn’t answer me, doctor!” – I urged Astrit again, after Mërkur left.

“I don’t know what you expect from me? You got the answer, do that yourself!”

“I wanted your opinion!” – I pressed him a second time because I knew his character, that he would explode hopelessly.

“My friend, knowing the communists, they will cause havoc! But this event had to happen to show the world that freedom does not die, even though for thirty years it has suffered under the fiercest violence humanity has ever seen. Thus, the value of the revolt will far exceed the consequences and the inevitable pain that will flow from it.”

“Do you believe in victory?”

“No. However, I hope the damages do not exceed the pain of the human limit. I think that national history will be enriched with a unique fact, which will have its effects later, will shake the foundations of the regime, and hasten its end. God grant that I am wrong and it does not take on these dimensions!”

We parted at the mouth of the mine, to meet again when the event took the dimensions he predicted. The second shift continued working, while the camp was buzzing. But I leave the floor to my friends for further developments.

Around half past three, as the first shift returned, the operational group arrived, consisting of the district prosecutor, Zef Deda, the chief of police, Rexhep Karaj, the head of the Security section, Gjergj Zefi, and the investigator of the Rrëshen Internal Affairs Branch, Shaban Domi, escorted by local police.

Since the square did not offer security, because a large mass of convicts had gathered, and so as not to hinder their dark intentions, they held their breath in Muhamet Kosovrasti’s infirmary.

There, under the pretext of filling out a report, they called Pal Zefi, but an escort of policemen brought him out in handcuffs. When the people thought they would take him to the cells, they crossed the tin gate and turned towards the entrance, at which point Dervish Bejko yelled: “Did you arrest our friend, you scoundrels?!” – Others echoed him: “Release our comrade! Release our comrade,” but the car was already heading for Rrëshen.

“Stop or I will shoot you!” – the soldier threatened from the upper platform, and the bolt clicked; “krrak-krrak.”

With the shouts: “Why did you arrest our friend, you scoundrels!” and; “Release our comrade! Release our comrade!” – the crowd changed direction and rushed the infirmary, where the operational group, with the contribution of Medi Noku, his henchmen, and perhaps the doctor, continued drawing up the lists, which they would update after forty-eight hours.

Around six o’clock, they arrested Syrja Lame and took him to the cell. Meanwhile, they tried to stop Pavllo Popa too, but those present took him under protection. To avoid confrontation, Pavllo agreed to surrender, but without handcuffs, “I come on my own feet!” he stated, but as soon as they crossed the tin door, the police broke their word.

Pavllo noticed the trap, turned back, and entered among his comrades. The police tried to forcibly extort him, but they met the vanguard, which responded to violence with violence. Then they threatened: “You are here, you have nowhere to go, we will take you again!” and left to save their heads, faced with the crowd’s anger.

In response, the enraged rioters rushed the infirmary to take the operational group hostage, but the military outside the fence somehow created a secret passage and freed them from certain sequestration.

From that moment on, no policeman was seen again. The camp was taken over by the convicts, as the gorge of Spaç echoed with the calls: “Down with communism!” “Long live free Albania!” “Either death or freedom!” “You are murderers!” “We don’t want to work in the gallery neither today nor tomorrow!” “Freedom for political prisoners,” etc.

I saw that one side used their hearts as a shield and the other side used heavy armaments; there was no talk of orders, the situation got out of control, and gradually, the revolt was turning into an uprising, although there were still no clear signs of organization. Memorie.al