From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part fifty-three

S P A Ç I

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My Memoirs and those of others)

Memorie.al / Now in old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whom the regime silenced and buried in the nameless pits? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, although I wholeheartedly tried to help my friends even slightly, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard those three days, I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

In socialist Albania, the masochistic experiment of class antagonisms continued. The authorities made every effort to conform the individual to dogma, making them lose their personality and, for its sake, deny social, friendly, familial, and even blood ties. Through the State Security (Sigurimi i Shtetit), the Party surveilled and threatened like the Sword of Damocles, from declared enemies to its own offspring, and even the Sigurimi itself.

Mayakovsky says in one of his poems: “When we say the Party, we mean Lenin; when we say Lenin, we mean the Party.” Here, the “Party-Enver” binomial surpassed the vampire of the steppes; it created a caste of bootlickers who fawned over him at every step, while the rest saw him as the chief executioner and the caste of bootlickers as a pack of ready hyenas, poised to tear apart anyone targeted by the chief executioner. Thus, the “Party-Enver” binomial reigned long, stigmatizing not only God but also the Devil.

The most unprecedented crimes in the history of this country were committed in the name of this symbiosis. The bootlickers caused thousands of innocent victims, just to please the chief executioner and build their happiness upon the misfortune of others. The moment they themselves turned into victims, many of them realized the damage they had caused, but it was already too late; the “Party-Enver” binomial had renewed the caste of bootlickers, who fawned over him and mercilessly struck the old bootlickers, as well as their entire retinue.

Therefore, I say that the pseudo-liberal moments were Enver’s staging, pretending to support certain individuals under certain circumstances, until he tightened the belt and liquidated them in groups or one by one. Thus, the liberalism of the first two or three years of the 1970s served as a gauge to check the pulse and deliver the next blow against the next enemies, and so on until his death and subsequently, until the end.

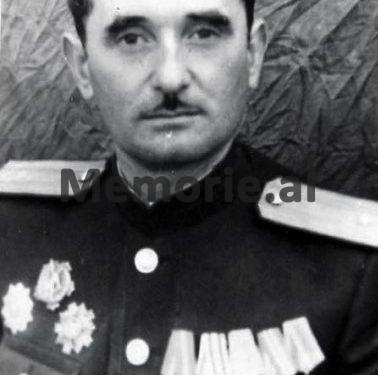

A Cynical Trio

One fine day, after four years of “success” in the Spaç mines and after decorating his chest with medals and filling his pockets with money, in the second half of 1972, Çelo Arrëza was transferred to the General Directorate of Camps-Prisons in Tirana. The appointment probably came as a merit for experimenting with every form of torture, from extreme violence to supposed leniency. If we were to make a scan of his reign, Çelo, the touchstone (guri i kandarit), would surely lean toward the negative side, for which the Party evaluated him.

He was replaced by Haxhi Gora, an old prison hunter who was just as ignorant and much of an executioner as the former, but more cunning, because he rarely entered the camp. However, when he did step in, there would certainly be major events, arrests, or unprecedented harassment, and woe to whoever’s turn it was to fall into his hands! The dull-headed and uneducated major, Shahin Skura, continued as the commissioner – a loyalist to the harsh line, who pretended to be educated, but all his knowledge was summarized in a few Party slogans, inapplicable in political prisons, especially in Spaç, where “rebels from all over Albania prevail,” as he himself expressed.

Meanwhile, the scoundrel from Korça, the operative Fejzi Liçaj, would cause the prisoners countless sorrows (due to his “merit,” four people would be shot in the Revolt of May 21, 1973, and they would even execute “Tartarini,” the fifth martyr!) They would also re-sentence over eighty prisoners, and even the prison itself! The trio of executioners – commander, commissioner, operative – would turn Spaç into HELL! Haxhi Gora brought back the old customs.

Beatings were now rampant for no reason, the pillars were filled with unlucky people who groaned and whose blood dripped from the tips of their blackened fingers, squeezed by the handcuffs (gjermankave) set to zero; the solitary cells had no more space, some spent the night in the open air, counting the stars in the firmament; medical reports were suspended, professional and infectious diseases were causing havoc; Sunday rest was forgotten; when rarely allowed, we were followed by the inspections and speeches of the ignorant Shahin Skura; working hours were doubled, any failure to meet the norm was punished, the food was cooked terribly, and the little that was given was insufficient and indigestible.

In the Old Furnace

After the accident, I was returned from the pyrite mines to the upper-level galleries of the third zone, even to the same brigade I had been separated from six or seven months ago. It was a privilege for me to work in a group with Mexhit Capa from Majtara e Dibra and Feim Lukra from Devolli. Feim was our miner, while Mexhit and I, as old friends and in unison of ideas, completed the “yoke of oxen.” We achieved the norm without straining ourselves too much, except for the first weeks when I still had health problems, but thanks to my kind colleagues, I got away without punishment.

In the camp, we continued the old organization. I ate bread with the two Tomors, but now Tomor Balliu and I were housed in the newly built palace in different rooms. I met Allajbeu less often because he would end up in solitary confinement for months and years, and the Revolt of May 21, 1973, would even find him there. After the death of his father, Nuredin, Allajbeu became severely embittered with the state. Before passing away, his father had left a living request that they should sing at his fortieth day commemoration, because he was escaping the woes of this world, the class struggle, and political punishments.

The request was not ignored by the earth, so on that very day, friends sang with broken hearts, but the stubbornness of the deceased caused trouble. The Sigurimi took it as a challenge, and the consequence followed: the participants of the funeral lunch ended up in prison for agitation and propaganda. Tomor responded to the Sigurimi’s irresponsibility with extreme acts, one of which was the unilateral termination of relations. He later boycotted work, claiming that as a political prisoner; no one had the right to physically exploit him.

However, his aspiration did not align with the objectives of the communist elite, which had based the prospect of building socialism – both successes and failures – on the backs of political slaves. Thus, an irreconcilable antagonism arose between him and the command, which feared the negative reference and the widespread diffusion of the phenomenon, and therefore responded with drastic measures. They used every form of violence but achieved nothing, and their cunning tricks did not work, until they brought in friends, acquaintances, and even his brother, Ali, who begged him to stop the stubbornness and return to work; he would perform the norm for both of them.

Thus began the series of punishments. Initially one month, then another month after that, and another, until he was “forgotten” in solitary confinement for years. When this kind of strike exceeded the limits of reality, Commander Haxhiu and Commissioner Shahini tried to stop it by any means. They tried to persuade him with enticements, but this method also failed, as Tomor stubbornly continued his strike like a mule. One day, those isolated in their cells followed this dialogue between Commissioner Shahin Skura and Tomor:

“Tomor, stop the strike and go to work with your comrades!” the Commissioner nearly begged him.

“Your request does not fulfill my expectation!” Tomor cut him off.

“We’ll find you easy work, man!”

“I was convicted for politics!”

“Agreed, but with forced labor, mind you!” the Commissioner insisted.

“Forced labor is for criminals. I am not one, Commissioner!”

“In any case, I advise you to stop it, or you’ll waste away in solitary!” Shahini feigned regret.

But Tomor was firm in his decision:

“I won’t work so that Nexhmije the whore can amuse herself!”

With this sentence, he added another gem to his rich repertoire.

Another time, he proposed that Tomor should crack walnuts, but Tomor dismissed him with disgust:

“I cannot expend that much energy, esteemed Commissioner!” Tomor ironized.

“What if we bring them already cracked?” Shahini proposed.

“They need to be peeled!”

“What if we make popcorn?”

“Regurgitation is the most bothersome process, Commissioner!?”

“What if we grind them, man?”

“That’s an interesting idea, but they require strength to swallow!”

Or the instance when the commander asked him to feed the command’s dogs:

“Take care of our dogs!” Haxhi Gora proposed.

“I do not belong to the canine species, Mr. Commander!”

“Ours are not just any dogs, but purebred hounds!” Haxhiu boasted about the red female dog with five or six puppies, who were basking in the sun a few meters away from the solitary cells.

“You ask me to service the red bitch?! To increase the puppies and then come and exterminate that species?!” Tomor alluded to the communist race.

“You still haven’t died in there!” Haxhiu cursed, slammed the door, and left without turning his head.

Precisely for these reasons, in the revolt of May 21, 1973, he would be sentenced to another 13 years, and after a few months, he would be locked away for years in Burrel prison. Even when he was released in the late eighties, they would stage a suicide by hanging, or a hanging in the sheep pen. But that topic belongs to a chapter of its own.

Sacrifice for the Brother

Around the end of ’72 or the beginning of ’73, Gjokë and Pal Zefi were brought to Spaç. The brothers from the villages of Shijak (Rrushkull village) had been sentenced, the first to 8 years and the other to 10 years, for agitation and propaganda, but mostly as brothers of a sister who had died alongside her husband in an armed clash with State Security forces.

Gjoka was assigned to our brigade, but he wouldn’t last long, following a trivial incident. One day in February, Gjoka had a cold and had wrapped a colorful scarf around his neck to protect himself from the cold Spaç air, but Preng Rrapi noticed it and immediately ordered him to remove it:

“What’s that rag you’ve got there, you?” – and poked it with the stick he held in his hand.

“A scarf,” Gjoka replied, coughing.

It was obvious he was sick, but Prenga insisted:

“Throw it away right now, or by G… the Party’s ideal, you’ll pay dearly!” – and pointed with the stick at a heap of rags near the gate.

“I’m cold, sir, I don’t want to get sicker!”

“Throw it away, I’m telling you!”

“I don’t know what trouble my scarf causes you!” Gjoka defended himself and tightened it even more.

“That’s civilian clothing, you! If you escape, you’ll get lost among the free people!” – and lunged at his head with the stick.

This unprovoked violence irritated the prisoners of the first shift, who were waiting inside, and those of the third shift, on the opposite side, who burst out simultaneously in solidarity with their fellow sufferer. Pali was among the workers of the third shift when he saw what was happening to his brother; he broke through the crowd and stood by him:

“Don’t hit my brother, man!” – he grabbed Prenga’s wrist just as he was tearing the scarf from his neck. Prenga, who was not used to being challenged, widened his eyes, looked around for a colleague, and blew his whistle: “friu-fi-fi-friu,” until the policemen huddled together.

“How dare you raise your hand against the Party’s people, you?” he spat at the prisoner.

“I won’t let you touch my brother as long as I’m alive!” Pali replied nervously.

“Now I’ll show you and your brother what a Party policeman can do!”

Meanwhile, the pack of policemen rushed forward, tied Pal with irons, and took him straight to the cell, while they snatched Gjoka’s colorful scarf and sent him to work. But this would be his last day in the mines, because afterwards, they would transfer him to Ballsh, so he would never meet his brother alive again.

This was the reason Pal was isolated in solitary confinement, but… but… the pear has its stem at the back! At first, we didn’t believe he could last the month in the cell. But we were wrong; the command had decided to punish him severely, to teach a lesson to all stubborn rookies. In the cell, Pal ended up with Tomor, who for months had become proverbial for his stoicism and his striking wit, with which he defied the command.

The characters of the two matched so well that after a week they became close friends, found a mutual understanding of ideas, and agreed not to work. Thus, following a scarf and three months of punishment upon punishment, the Revolt of Spaç began, taking terrifying proportions. The state’s greed could not intimidate Pal, who responded to violence with violence and incited his fellow sufferers to vent the resentment that had been simmering for a long time, just like a dormant crater in the heart of the earth. Thus, Pal Zefi would become the promoter and one of the sacrificial victims of the Revolt.

Naturally, this was only one element, because other factors, like embers under the ashes, were waiting to ignite the fire that would consume the prison administration and shake the monolith of state compactness. After this, the communist hierarchs would find no remedy! As a result of the fear of retribution and the terror of the crimes committed, the Great One (Enver Hoxha) would suffer a heart attack; the moth of dilemma would gnaw at everyone, even the witch in the bed! Doubt about the loyalists stimulated his paranoia and pushed him to start the decimation, fabricating anti-Party and putschist groups in Culture, the Army, the Economy, and politics.

He sank so deep into his own madness that the backdrop of the Politburo portraits would change every season; thus, the former members would be replaced with workers, peasants, cowherds, and lumberjacks unknown even in their own villages! After executing the deceased, he would rot the rest in prisons, while their families would be deported to internment camps, to the periphery. But these belong to the following years, so let’s return to the course of time.

So, as I emphasized, the repressive actions, both misplaced and justified, the ban on meetings and correspondence with relatives, plus the sudden inspections – which were followed by the confiscation of books and notebooks, with extreme violence against anyone caught with forbidden items that they themselves had once allowed – negatively affected the psychological health of the prisoners.

For nearly three months, we were not given a single Sunday off. On Monday of every week, the first shift returned as the third, the second as the first, and the third as the second. We entered the mines exhausted and came out ragged, without food, without sleep, without washing! Accidents increased at the frontlines, violence increased, and the rope reached its breaking point!

The Revolt of May 21, 1973

In fact, the signs were visible the day before. Pal Zefi completed his third month, but he was left in the cell without explanation. At the same time, the guards faced the opposition of a spontaneous group who refused to go out to work. But what happened? May 20, 1973, was a Sunday, but the first shift was sent out at five o’clock. Although their teeth rattled from inflammation, fatigue, and the dirt of copper and pyrite ore, to the point of self-disgust, they did not resist sufficiently, excluding a negligible minority.

By law, Sunday was recognized as a rest day, but with the arrival of Haxhi Gora, it was transformed into an action day, updating the diabolical slogan: “Spaç remains the grave of the people’s enemies.” Thus, they implemented the motto: “You will not leave the mines, neither alive nor dead!” and increased the violence and suspended the vacations.

As per custom, the internal policemen started the day with the solitary cells so that they would be free when the wake-up signal was given. Before five, they took the detainees out to the washrooms, took away their blankets, locked their doors, and blew their whistles for the first shift to wake up, so that six o’clock would find them lined up. They did the same that day. But they became aggravated with Pal and locked the cell; they entered the camp and urged the others to act quickly, but some did not obey, which woke up the commissioner, who came with swollen eyes and promised that from the following Sunday, the regulation would be implemented. Thus, Sunday ended with the protest of that minor group, without any significant damage.

The Chronology of Monday, May 21, 1973

After thirty days, Pal was taken out of solitary for one day, and the next day he was sentenced to thirty more days. When the month was completed, they did not release him, but he left on his own initiative. When they asked him to return to the cell, under the pretext that the policeman would let him out after filling out the form, he refused, but occupied the shower terrace and threatened to throw himself onto the wires if they approached. With the mountain man’s word of honor (besa), Shahin Skura returned to the cell, but the commissioner violated the besa. Ultimately, they kept him for another thirty days.

Thus, the first month was followed by the second and the third. On May 20, they were supposed to release him, but Fejzi Liçaj had ordered not to let him out. Pal contested the decision, but no one listened to his protest. On the morning of May 21, when Mark Tuçi opened the doors of the solitary cells and ordered the isolated people to hand over the blankets and go to the washroom, he seized a moment of mental distraction and left.

The policeman spotted him on the threshold of the connecting door, but even when Mark Tuçi promised to release him himself, he refused to obey the order to return because he had lost faith in the institution of besa. The policeman threatened him, but he grabbed an iron bar from the pile of inert materials at the foundations of the building under construction and crouched under a rock surrounded by bushes. So, he responded to the insistence to return to the cell with the clanging of the lever.

The corporal saw that he had failed and informed the guard officer; Fejzi Liço happened to be on duty that day. He called Ndue Lleshin and Zef Bardhoçin, and the four of them attacked Pal. But when they found themselves under the threat of the bar, they understood that this was not about a psychologically ill person whom they could persuade, even with the help of a doctor. The prisoner facing them seemed determined in his purpose.

“Go back to the cell!” Fejzi Liço spoke softly.

“I completed the month yesterday, sir!” Pal replied.

“We record the months, you!” Zef Bardhoçi swelled up.

“Go guard the goats, you wretched man, I don’t have time to deal with police!” Pal insulted him.

“Now I’ll show you the goats, you corpse!” the policeman threatened, but he avoided the clanging of the bar.

“Don’t come closer, whoever dares will meet the bar!” Pal gnashed his teeth from the base of the rock. Meanwhile, the back-and-forth movements increased near the washroom, the faucet, and the soup cauldron, but they froze before this scene of violence. After a few minutes, Gjet Çupi, Ndue Prenga, Frrok Deda, and Skënder Ndnini crossed the tin door, while Medi Noku, with a couple of assistants (zarbo), came from the technical office to help. In the midst of this commotion, the camp was thrown into disarray, and the mess woke up the second shift as well. Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)