Memorie.al / Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutionary and a key figure in the October Revolution, second only to Lenin, recounted the shocking massacres of Serbian soldiers against Albanians as early as 1912, in the famous Ukrainian newspaper ‘Kievskaya Misl’. He would later become the founder and commander of the Red Army and the People’s Commissar for War, but, under Stalin, he was expelled from the Communist Party and deported from the Soviet Union in 1928. Trotsky was finally assassinated in Mexico in 1940 by a secret agent of Stalin named Ramon Mercader, who struck him in the head with an ice-axe (mountaineering pick), and Trotsky died a few hours later in the hospital. His ideas formed the basis of Trotskyism, a major school of Marxist thought.

Long before the Russian revolution, in September 1912, Trotsky was sent to the Balkans by the Kiev newspaper “Kievskaya Misl” as a war correspondent to cover the Balkan Wars in Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania. Below is one of the articles that Trotsky sent back to his newspaper, a report on the atrocities committed against the Albanians of Macedonia and Kosovo, in the wake of the Serbian occupation in October 1912.

‘Behind the Curtain of the Balkan Wars’

Leon Trotsky’s shocking accounts of Slavic violence and genocide against Albanians in 1912–1913, for the newspaper ‘Kievskaya Misl’.

I had the opportunity, for better or for worse, to visit Skopje a few days after the Battle of Kumanovo. Right from the beginning, I was irritated by the Belgrade authorities regarding the travel permit. From the obstacles that the Ministry of War placed in front of me, I began to think that the people who were leading the war did not have a clear conscience and that down there; they were carrying out actions completely different from what was presented in the official press. This impression or premonition was reinforced when I met an officer who had stayed in Skopje with the General Staff soldiers.

This officer, whom I had known for a long time, was an honest man. However, as soon as he found out that I was going to Skopje, since I had actually been given permission to go there, he told me, with an openly hostile attitude, that I should not go there and that he did not understand what Belgrade was doing, according to him, when it allowed “foreigners” to go to Skopje. In Vranje, on the border with Serbia, when he realized that I would not change my mind, the Serbian officer changed his tone and began to prepare me for the scenes I would see when I arrived in Skopje. “These are unpleasant things, but unfortunately, they are inevitable,” he told me.

I must admit that all of this made me even more suspicious. This meant that the wicked deeds, which had been heard of even in Belgrade, were not accidental; they were not specific or isolated cases, as long as an officer treated them as “state necessities.” Someone must have had information about these. Who? The Army? Or the Government? I learned the answer to these questions as soon as I arrived in Skopje. The sadness began as soon as we crossed the border. At 5 p.m., we approached Kumanovo. The sun was setting, and darkness had already set in. The darker it got, the more the flames of fire going upwards could be seen. Everything around us was burning. All the Albanian villages near and far, had turned into plumes of fire, right up to the railway.

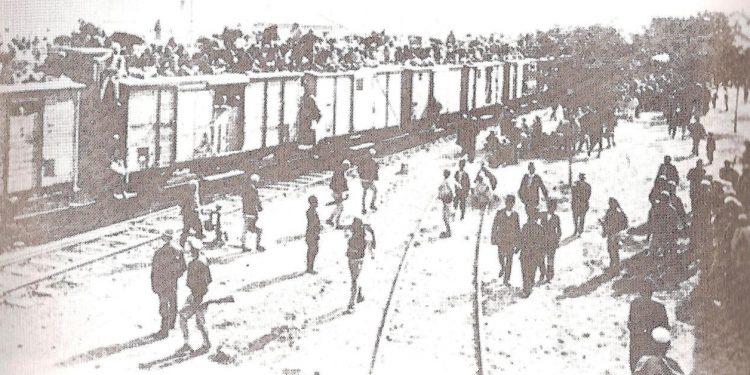

This was a unique example of a terrifying destructive war that I have seen in the combat zones. In an instant, the property of those people, inherited from their grandparents and great-grandparents and acquired with effort, was turning into flames. This monotony of fire followed us all the way to Skopje. I got off the wagon I had traveled in. The whole city was silent; you couldn’t see a living soul on the streets. Only in front of the train station was there a group of soldiers, from where the sounds of drunken men spread.

Everyone went their own way, while I remained alone at the station. I went to the group of soldiers. Four soldiers held their bayonets at the ready. In the middle of the group of soldiers stood two young Albanians, wearing white plis caps. A drunken Četnik soldier held a knife in one hand and a bottle of rakia in the other. The Četnik ordered the Albanians to lie down on the ground. They, half-dead from fear, knelt down. After the next order, they got up. He repeated this several times….!

Then the Četnik, cursing and threatening them, pointed the tip of the knife at other victims. He forced them to drink rakia, then… he kissed them. Drunk on power, rakia, and blood, he was amusing himself by playing with them, just like a wild cat with mice. The same actions, the same psychology. The three other drunken soldiers stood guarding, lest the Albanians escape or resist, while the Četnik was entertaining him.

“These are Arnauts,” a soldier told me, “now he will slaughter them.” Out of fear, I left the group. It made no sense to try to protect the Albanians. They could only be saved from these soldiers by an armed force. This entire scene was playing out at the train station, and when the next train arrived, I left so as not to hear the terrible screams and the Albanians’ calls for help…!

The streets of the city and the city itself were so quiet that it seemed deserted. All the doors had been closed since six in the evening. As night fell, the Četniks began their work. They violently entered the homes of Albanians and Turks, carrying out their acts of murder and looting. Skopje had 60,000 inhabitants, half of whom were Albanians and Turks. Some of them had certainly fled, but the majority had remained. And now, crimes were being committed against them during the night. Two days after my arrival in Skopje, the first thing that would be seen in the morning was the pile of corpses of Albanians with shattered heads, under the Vardar Bridge, right in the center of the city.

Some said they were Albanians who had been drowned by the Četniks; others said the river water had brought them. Only one thing was known: those people had not been killed in battle….! Skopje had turned into an ordinary military camp. The population, especially Albanians and Muslims, hid in the streets so as not to be seen by Serbian soldiers. Among the mass of soldiers, Serbian peasants were also noticeable, having come here from various parts of Serbia.

Confessing that they had come to find their sons and brothers, they passed through Kosovo, looting. I talked to three of those “bag-carriers.” The youngest of them, a short man, of the “hero” type, boasted about how he had killed two Albanians with his rifle, but two others had escaped. His companions, elderly peasants, confirmed his story. “One thing is not good,” they complained. “We don’t have money with us. Here you can take as many oxen and horses as you want. A soldier’s pay is two dinars (75 kopecks).

The soldier goes to the first Albanian village and takes the first horse he finds. Through the soldiers, you can get a head of oxen for 20 dinars. Serbs from the Vranje area have massively set off towards Albanian villages, with the aim of grabbing everything they find. Serbian women have loaded doors and windows onto their backs, taken from Albanian villages. Meanwhile, two soldiers arrived. They belonged to the units that were disarming the Albanians. One soldier asked where he could exchange a lira. I asked him to show me the lira, as I had not seen a Turkish coin.

The soldier first looked sideways, and then pulled the gold coin out of his bag, admitting that he had others but did not want to reveal the amount. One Turkish lira was exchanged for 23 francs. Other soldiers arrived. I was listening to their conversations. “I don’t know how many Albanians I killed,” one said, “but on none of them did I find anything valuable to take. And, when I cut off the head of a young bride, I found 10 liras on her.” They spoke completely freely about their deeds. This was common for them. People do not understand how many internal changes only a few days of war have brought.

One can see to what extent a person depends on circumstances. Under the conditions of a barbaric war organization, people quickly become brutalized, and they probably don’t even realize it. A platoon of soldiers was marching down the main street of Skopje. A drunken man, most likely a captured Turk, started cursing them. The soldiers stopped. They leaned the Turk against the nearest wall and shot him on the spot.

The platoon continued, as did the people who were on the street. That evening in a tavern, I met an officer whom I knew. His unit had been stationed in Ferizaj, in the center of the Albanians, “Old Serbia.” With his men, the sergeant had towed large, dangerous cannon during the march, from Koçani to Skopje. These cannon would be sent to the army that had surrounded Edirne (Adrianople).

“What are you doing now in Ferizaj among the Albanians?” I asked.

“We are roasting birds and killing Arnauts. We are tired now,” he said, grimacing and yawning from fatigue.

“There are many rich people among them. Near Ferizaj, we entered a rich village, with houses like castles. The owner was a wealthy man who had three sons. There were four men and many women. We dragged them all out of the house, lined up the women, and cut the throats of the men in front of their eyes. The women didn’t cry from fear. They begged us to go into the house and take their clothes. We allowed them. They then gave us a gift. Then we set fire to the whole place…!”

“How can you act so brutally?!” I asked, horrified by his story.

“I don’t know myself – you get used to it. At another time, I wouldn’t have been able to kill an old man or an innocent child. In wartime, as you know, the commander gives orders, and you must carry them out.”

“Many things like this happened not long ago. While transporting that cannon to Skopje, we encountered a cart on the road in which four men were lying, covered up to the waist. I immediately smelled iodine. Something was suspicious, I thought. I stopped the cart and asked them who they were and where they were going. They were silent, excusing themselves that they didn’t know Serbian. Only the cart driver, a gypsy, was with them, who told us that the four wounded men had participated in the fighting in Merdar. They had been wounded and were now returning home. I understood what they were.

“Get down,” I ordered.

They understood what I was telling them, but they hesitated.

“What to do? I fixed the bayonet on my rifle and stabbed all four of them….!”

I knew that man. He had been a waiter in Kragujevac. A man without any qualities. Not warlike by nature, a waiter, just like all waiters in other places. He was even in the Waiters’ Union for a while. He was even the secretary, but he left…! And look now, what he has turned into!

“Why are you acting like bandits, killing and looting, without making any distinction?” I shouted, feeling disgusted with the man I was talking to. The officer was in a difficult situation. It seemed like something had occurred to him. Then, trying to justify himself, convinced and serious, he uttered a phrase that cast even more darkness than I had seen and heard.

“No. That is not the case. We, the regular army, rigorously adhere to the rules; we never kill anyone younger than 12 years old. I cannot tell you anything for sure about the Četniks. They are a law unto themselves. I can vouch for the soldiers.” The sergeant did not vouch for the Četniks. And indeed, they accepted no restraint. Recruited from among the unemployed, the incapable, the bad and worthless elements, from the lowest mob, they indulged in their savagery with crimes, looting, and violence.

The deeds spoke volumes against them. Even the army and the state felt uncomfortable with such bloody banalities of the degenerate bands. They were forced to take measures and, even before the war ended, disarmed them and returned them to their homes.

I was unable to endure that atmosphere any longer; I did not have the stomach for it. Political interest and moral conscience, to see with my own eyes how such things are done, sank. Now I had only one desire: To return as soon as possible. I found myself in the wagon again. I was looking at the wide fields around Skopje. What beauty, what expanse!

People could live well here. What is the use of speaking, when you already know these ideas; only in that place did they resonate ten times louder to me. Fifteen minutes after the train departed, I looked outside and saw a corpse with a plis on its head, face down, and hands outstretched, about 200 yards from the station. About 50 yards towards the railway, two Serbian guards stood, part of the forces guarding the railway. Surely, this was their work. Further, further, to get away from this place as quickly as possible.

Not far from Kumanovo, in a meadow near the railway, soldiers were digging a large pit. I asked them what the pit was being dug for. They told me that the pit was being dug for spoiled meat, which was in ten or 15 trucks that were stationed on the side of the road. The soldiers had not taken the meat that belonged to them. All their food needs, and even more; they took from the homes of the Albanians: cheese, milk, honey. “I have eaten more honey, which was taken from the Albanians, in that time than I have eaten in my entire life,” a soldier whom I knew told me.

Every day, Serbian soldiers slaughtered oxen, sheep, and pigs, chickens, which they ate and threw the remains aside. “We don’t need the meat. How many times have we written to them in Belgrade not to send us meat, but they do it, according to some rules.” That’s how things stand when you look closely. The meat is rotting, both the meat of humans and animals, the villages have been reduced to ashes, and people are being expelled. “People over 12 years old”… everyone has been brutalized, losing their human face…

War comes to the surface, as the main and most important thing; you will see the crimes if you pull back a little the curtain that hang before the deeds of the soldiers’ “bravery”…! Memorie.al