By Michael Dobbs

– “In Albania, they are watching the soap opera ‘Dynasty’ from Belgrade television and it seems that change has begun, as Ramiz Alia, as a Muslim Gheg, is appointing his people to the top leadership…” –

Memorie.al / Perhaps nowhere has the death three months ago of the Albanian leader Enver Hoxha been analyzed with more care than it has been in Yugoslavia, a country whose stability is directly influenced by the policies of Europe’s most secretive state. Stalinist Albania has figured in many of the “worst-case scenarios” dreamt up by people whose job it is to analyze the future of the Balkans, Europe’s most volatile region.

Should the small, mountainous country on the Mediterranean return to the Soviet fold, it could create serious problems for its Yugoslav neighbors, because of their politically tense ethnic Albanian minority? Thus, one analyst of the bilateral Albanian-Yugoslav relationship listened intently as an Albanian official described the intricate plot of the American television series “Dynasty.”

It turned out that, for all his Marxist-Leninist rhetoric, the official was a devoted fan of the capitalist soap opera, which is transmitted in English by Yugoslav television, whose frequency reaches the Albanian capital, Tiranë. A small incident at first glance, but it is a very clear indicator of how Albania is gradually – very gradually – emerging from four decades of self-isolation.1

Just a few years ago, watching foreign television stations was strictly forbidden, as were other symbols of the “decadent” West: long hair, reading the Bible, or driving a priv2ate car. In the view of the Yugoslavs, Albania’s new leaders are now at a historic crossroads. An ever-increasing economic crisis and a desire to alleviate the difficulties of daily life favor an opening of the country to the outside world for Albania’s 2.5 million inhabitants. But the political legacy of Enver Hoxha, a fierce brand of nationalism, and fractions within the leadership make immediate change dangerous and impossible.

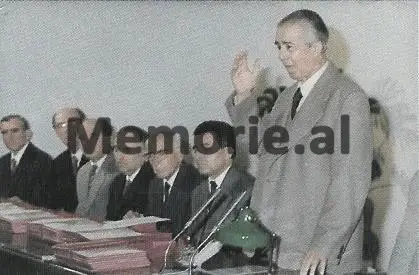

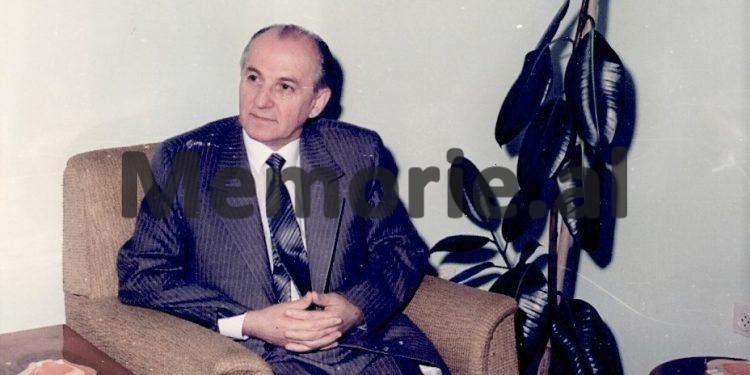

In Yugoslavia, both Western diplomats and Yugoslav analysts agree that Hoxha’s chosen successor, Ramiz Alia, 59, is still consolidating his political power following his appointment as First Secretary of the Albanian Party of Labor last April. As a Muslim Albanian from the North, i.e., a Gheg, he must tread particularly carefully in a leadership dominated by Tosks (Southerners).

“If Alia feels insecure above all else, he will continue to pursue the current policies, even if the political situation is difficult,” says a Yugoslav official. “Once he stabilizes and installs his own people in key posts, then perhaps there can be some changes.”

Last week, Albania published several foreign policy statements of Hoxha after the leader’s death, expressing opposition to tangling political and trade ties with states of different ideologies. Western analysts appreciated this repeated statement and took confirmation that change would not be immediate.

Albania’s current economic problems result from the split with China in the late 1970s, leaving the country without a patron for the first time in more than four decades. Hoxha, a French-educated teacher who led the uprising against the Italian occupation during World War II, cut off alliance ties with Yugoslavia in 1948 and the Soviet Union in 1962.

The few Western visitors allowed into Albania seem to step back into the 19th century. Agricultural techniques are primitive, with the exception of the Steel Combine in the central Albanian city of Elbasan, built with Chinese aid, while many other factories appear to Western eyes as relics in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution.

Deprived of Chinese or Soviet aid, the only way to open up Albania and modernize its old assets is to increase foreign trade. Taking loans is forbidden by the Constitution, so all trade is done primarily through exchanges. According to Yugoslav statistics, the total foreign trade turnover now amounts to the small figure of $800 million U.S. dollars per year.

Albania exports chrome (it is the world’s fourth-largest producer of this mineral), electricity, and oil, which it exchanges for machinery it cannot produce itself. “Their economic difficulties seem to be increasing,” says a Yugoslav official. “Day by day, the official media speaks of fewer cuts. It is clear that the Albanian leadership is preoccupied with internal problems.”

Like the United States of America, Yugoslavia has a clear strategic interest in preventing the Soviet Union from gaining access to the Albanian warm-water ports on the Adriatic. On this point, they have been encouraged by Alia’s harsh refusal, following a message of condolence that came from the Russian leadership after Hoxha’s death, a clear sign seeking the start of a new era of relations between the Kremlin and Albania.

Yugoslav leaders are also concerned about what they see as Tiranë’s attempts to incite tensions among the 1 million ethnic Albanians of Kosovo, the Yugoslav province on the northern border with Albania. The political climate in Kosovo is still tense following the serious rebellion in 1981, when Albanian demonstrators demanded federal republic status for the province.

In the view of many politicians in Belgrade, this would be the first step in the disintegration of Yugoslavia into a multinational state. The delicate ethnic balances are threatened by mass exoduses of Serbs from Kosovo, due to Albanian threats and population pressure. Ironically, Albanian economic backwardness and the harsh nature of its regime can be viewed as serving short-term Yugoslav interests, from the perspective of some analysts.

Although many Yugoslav Albanians view Albania as their motherland, they are also aware that the standard of living on the other side of the border is lower than theirs. Following the encouragement of cultural ties between Albania and Kosovo in 1970, Yugoslav officials are very sensitive to what they refer to as Tiranë’s “interference” in the region.

Talks for a new cultural exchange agreement were interrupted last November, with Yugoslavia accusing Albania of refusing to recognize the rights of Yugoslav minorities. The first railway network between Albania and the rest of Europe will be inaugurated later this year, after work is completed on the line linking Yugoslav Titograd with Shkodër, in Northern Albania.

But the Albanians have given a clear signal that this is not an immediate opening to the outside world. When the Yugoslav side recently suggested a regular railway passenger service between the two countries, the idea was rejected by Albania. At least for now, the Shkodër-Titograd line trains will transport freight with chrome – not people. Memorie.al

The author of the article was a Foreign Service correspondent for the “Washington Post” in Belgrade. Prepared for publication by Androkli Dralo.