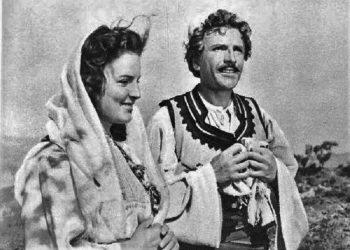

Memorie.al / Shadije Bogdo, a politician, patriot, feminist, and educator of the early 20th century, were unique. Considered the “Thatcher” of modern times, she spoke courageously about political space for women, in a patriarchal isolation. Open-minded, a brilliant connoisseur of politics within and outside the borders, she laid the foundations for the woman-politician. “Enough then, ladies, of the tyranny we have endured until today, the cause of which is ignorance and the failure to strive for our freedom. Here is the opportunity to show that we women are also capable of participating, perhaps even more than men, in the awakening of our homeland!” (Article in the newspaper “Bashkimi,” year 1924).

She developed as a figure and a personality. We see her in 1924 in genuine, concrete political movements, a member of the “Bashkimi” (Union) Association, with her brother Fuad Asllani, the association’s vice-chairman, and her husband, Sulo Bogdo, in the leadership. This association, with its activity and functions, had the stature of a political party. Together with Fan Noli, after the failure of the political June Movement, the Bogdo couple immigrated to Italy in December 1924. Her return to the homeland, before the announcement of amnesty for political emigrants, brought Shadije face-to-face with the Zog regime, which imprisoned her as an anti-Zogist. The Parliament of the time reacted, arguing that a woman could not be imprisoned for politics.

After her release from prison, she was interned in Kavajë. The Zog regime created an apolitical environment, not allowing genuine party movements, limiting the elite, even in their political convictions. Zog placed the elite opposite him; for and against him. A part of it considered Zog a figure for strengthening the state and its consolidation. Another part of the elite, including Shadija, considered him an obstacle to realizing the ideals for strengthening a democratic state and republic.

She was for a democratic republic, with a social-democratic tendency. At that time, Western and Eastern Europe were facing extremes, such as communism and fascism. It is global and economic crises that shift political wings toward the poles, proving dangerous, leading to the outbreak of a hot world war. Wise and cold-judging elite, beyond the ambition for power and analytical towards economic crises, without falling into despair or depression, collective anxieties, and fears, would certainly reflect and distance it from extremes. This was the social-democratic tendency, which was encompassing the Albanian political elite, certainly including Shadija.

Musine Kokalari succeeded much later, almost 20 years later, in founding a social-democratic party. During this time, many progressive democratic women’s organizations and associations were created. The woman-politician could not but shine in the “Shqiptarka” (Albanian Woman) association, founded on March 28, 1924, in Tirana, elevating its stature toward political activities. The association politically protested against the assassination of Avni Rustemi, and demanded the arrest and punishment of the perpetrator.

In December 1924, when the governments of neighboring countries undertook a campaign against the democratic government of June 1924, the “Shqiptarka” Society organized a demonstration, attended by 100 women, who, with the national flag, protested in front of foreign representations, addressing this telegram to the foreign powers: “Gathered before the danger threatening the existence of the homeland, we call on you to use your influence to stop the direct support given by the Yugoslav government for the movement that disrupts the tranquility of the homeland.”

With the “Shqiptarka” society, her feminist figure also stands out. Against physically and mentally “covered” women, stood the unquestionable, imposing, suffocating male superiority. “So, courage, ladies! What we did not do, our daughters will do. Let us join hands and help the cause of feminism in Albania. The civilization of a nation needs the awakening of women,” – she wrote in the newspaper “Bashkimi.” It is only the year 1924, and she is laying the foundations of Albanian feminism, as well as the role of civil society. The “Shqiptarka” Society was chaired by Shadije Bogdo.

According to the statute (drafted by her), the goal was the fight against the yoke of the Albanian woman, the improvement of her social condition, and opening the way for her to become a factor in all fields of life. “Women are half of humanity, so a nation is called progressive when the other half, women, walk side by side with men” (Sami Frashëri). “How can a nation prosper when women are kept locked in cages? Women should be more educated than men. The woman is the mother of the child, the mistress of the house, and the entirety of humanity” (Naim Frashëri).

In the same conceptual line as Sami Frashëri, Naim, and other Revival figures, a female voice also stands out. “The woman, besides domestic duties, has greater duties in the work of the homeland, because mothers instill those patriotic feelings in the hearts of boys, with which the patriot who will defend his country with sacrifices of life is later formed. To give the boy these high feelings, the woman must first have them herself; and she cannot acquire those feelings except in school. To well understand what part the Albanian woman takes in social life, let us first look at the part she has in the child, which is like a small mirror of a state,” – Shadija publicly stated in the press of the time.

The Gordian knot, the microcosm (the child) and the macrocosm (the state), inextricably linked to the woman-child, the educated woman-mother, the intellectual woman, the patriotic woman, in a period when the Albanian state was still fighting for existence and survival as a nation, ultimately resulted in patriotic movements that completed the framework of national movements. Initially, an illiteracy course was opened in the “Shqiptarka” association, led by Shadija herself, which was an important step for the time.

The embroideries produced by the association members were sold, and the collected revenues helped Kosovar refugees. This contribution, more than material value, had patriotic value. The society was directly supported by democratic revolutionary elements, such as Avni Rustemi and his comrades. The association was truly a branch of the “Bashkimi” society. Shadija, above all a visionary regarding the essence of European civilization’s progress, fought strongly for Albanian education.

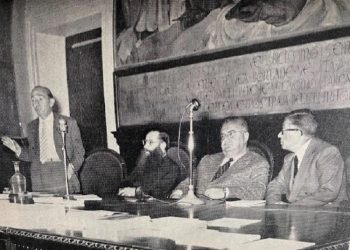

After 1908, with the unification of the Albanian language as an important means for national identification, the elite were preparing the ground for strengthening the foundations of Albanian education. She fought with the conviction that education was the only way to strengthen national consciousness, in a period of confusion and state-forming efforts. Her name is seen in the Educational Congress of 1922, which demanded improvements and changes in the structure and content of the school, in adaptation to the time, mainly aiming for its secularism.

In this congress, Shadija conveyed her experience in opening the first girls’ school in Libohovë. The efforts for the secularization of the school did not end there. They would continue, especially in the Education Congress of 1924, where her figure gains value as the initiator and organizer of this congress (this was also a task assigned to her by the “Bashkimi” association). It was no coincidence that the new forum of educators gathered and held its proceedings in the premises of the girls’ school, where Shadija herself worked. The newspaper “Bashkimi” dated August 15, 1924, on its front page, begins the article about the educational congress: “On the 12th, at 5 o’clock, the educational assembly opened in the Girls’ School, attended by 33 delegates.”

(Shadija was the director of the Girls’ School, and this was the reason why the congress was held in those premises). The Congress decided to develop education on scientific and democratic bases. The emphasis on these two demands, alongside each other, spoke of the influence of the democratic movement of the time and the political maturity of the delegate teachers. The Congress voted on some of Shadija’s demands, one of which was compulsory primary education for both sexes in state schools. The Congress viewed the schooling of the Albanian female as important, both for the near future and for the long term, and both within and outside the school.

Besides compulsory schooling for the Albanian girl, the Congress decided to recommend to the Ministry of Education the creation of a Female ‘Normal’ School, which was another one of Shadija’s proposals. Based on this proposal, the “Nëna Mbretëreshë” (Queen Mother) Institute was later opened. Her figure stands out alongside Aleksandër Xhuvani and Jani Minga, Ramazan Jarani, Mehmet Vokshi, and their comrades. This was the second educational congress where she was an organizer.

Shadija, in addition to political, patriotic, and feminist activities, performed an extraordinary job in Libohovë, opening the first school for women in October 1920. The work would begin with raising awareness and consciousness of a nation, newly emerged from a dark era. “Today the government, seeing that the civilization of a nation needs the awakening of women, began to open girls’ schools in those centers of Albania that have more importance” (Shadije Bogdo’s speech on the first day of school).

In the speech on the first day of the school’s opening, she provided an overview of the economic and educational situation left by Turkey, Greece, or even Italy, who had followed a nonexistent educational policy. In the first steps, it was not easy. She had to work with parents and the girls themselves to convince them that the school was a place that would teach them and nourish them with love for much-suffering Albania. The opening day of the school turned into a popular celebration. The multi-dimensional woman would utilize the progressive ideas of the time, as well as the pedagogical tact, to overcome the generations-deep rooted suppression.

Against the century-old veiled women, stood the woman-violinist, who, with the imagination of an artist, would prepare and organize cultural and artistic activities. With the completeness of her formation, including American pedagogy, she gave special importance to extra-curricular activities, as an important factor for the cultural and patriotic formation of the students. The repertoire of theatrical and musical performances, some authored by Shadija herself, served not only for moral and patriotic education but also for bringing students of different religious faiths closer and fostering brotherhood.

She had to work psychologically with girls with domestic mindsets, creating a relationship of love with them. I. Kumbaro (a student of Shadija), writes in her memoirs: “She was the best teacher in the world; we loved and appreciated her so much.” Zejnepe Bejleri, another student, says that; “She worked a lot with other girls, outside of school, to remove the çarçafs (veils) and she had succeeded in her goal.” These testimonies show her struggle for the emancipation of women, starting with the removal of veils.

It was a very difficult initiative, but it yielded results at the time. Shadije Bogdo was later transferred to Tirana as the director of the capital’s girls’ school, alongside Mati Logoreci, director of the boys’ primary school, continuing her work as a teacher and simultaneously a feminist for women’s rights. In 1926, we see Shadija as the first teacher at the American Girls’ Institute, where she was described as a teacher with a high educational level.

We go back in time, nearly 100 years, and visualize a school (the American Girls’ Institute), which shapes culture, but above all, characters, an integral and very important part of community well-being. The American teachers created human and intellectual relationships with their Albanian colleagues, as equals, which also indicates the intellectual level, educational professionalism, and civic education of the Albanian teachers who walked alongside the American teachers, such as Shadije Bogdo.

In the place of knowledge, Americanizing and consequently de-nationalizing tendencies were not apparent. The Albanian teachers were completely free to work as Albanians in all subjects, especially in Albanistic subjects, such as; language, literature, geography, history, subjects that Shadija taught the students. The goal was, first and foremost, to prepare the citizen-person, with free thought and striving for legal justice, as fundamental means of democracy, and then the specialist.

In truth, with the civic formation the students received, the foundations for the adoption of American democratic ideas were being laid, which unfortunately, historical fate left halfway. Despite the mudslinging from the communist regime, these schools still remained as shrines and their teachers as saints, as the best exemplary model to follow, especially by those involved in the education of the generations of a nation.

The woman with endless energy developed a real activity for raising the potential woman’s mental and intellectual awareness. She goes beyond the boldest visions even for modern times, where the 30% quota of women politicians in Albania has remained artificial, not at all real. In the 1920s, the 25-year-old Shadija claimed Albania was in the elite of countries, as not all European countries had the awareness and emancipation of women’s participation in politics. Switzerland gave women the right to vote in 1960.

“They have achieved not only personal freedom but also political freedom. We see in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and finally in England, Germany, and Austria, that women participate in the governance of their country. If we are not at the level where women are in Europe, the fault lies with us women, more than with our husbands and fathers” (Shadije Bogdo, newspaper “Bashkimi”). Today, a woman with political ambition is considered normality, while the state visions of an Albanian female, a century ago, were unimaginable, even bordering on heresy.

The mindset of the woman politician arises from radical changes, from awareness of the real situation, from internal enlightenment and impulses. Her wisdom understands the essence of evolution: to start change from within oneself. Albanian politics today is still caught in the loop of self-exoneration, blaming others. With clear ideas, throughout her activity, she fought for the consolidation of the society’s supporting pillars: education, economy, and the development of women. “Our beloved country was covered by the black cloud of ignorance and fanaticism, which endlessly cause the economic impoverishment of a country” (Shadije Bogdo, newspaper “Bashkimi”).

Women who have overcome unquestionable male authority and power have been rare even globally. Historical circumstances have placed such women on a pedestal. But there are also women who, during their activity, had to overthrow extreme circumstances to enable their activity. Having studied at “Robert College” in Istanbul, she perfectly knew four foreign languages: English, French, Turkish, and Italian.

In the communist regime, the woman with Western, pro-American culture, with a son in emigration, and her brother in the prisons of the dictatorship, was left in the shadows, nameless, voiceless, as she was viewed with distrust by the political power. She was laid to rest without any official ceremony, according to the merit she deserved. She is decorated “For high patriotic activity” and has also been honored by the people of Libohovë with the title “Honorary Citizen of Libohovë.” The year 2012 places her in the encyclopedic calendar of “Radio-Vala.” Memorie.al