The Third Part

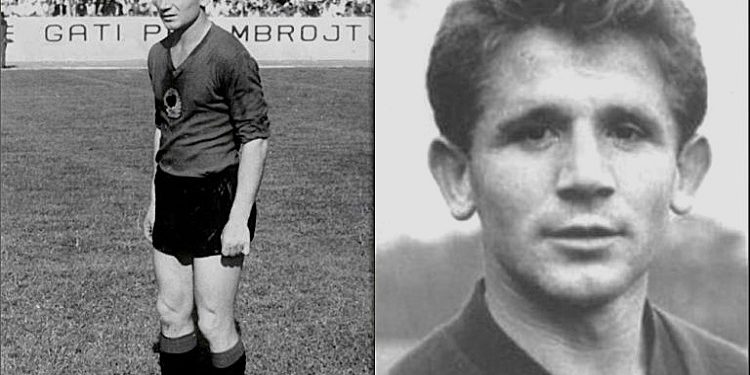

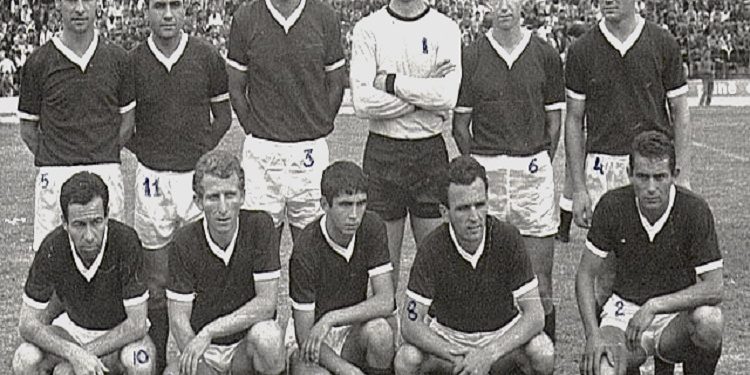

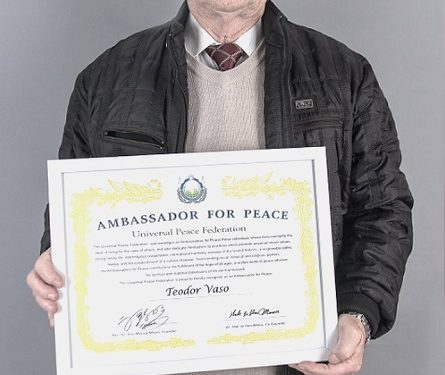

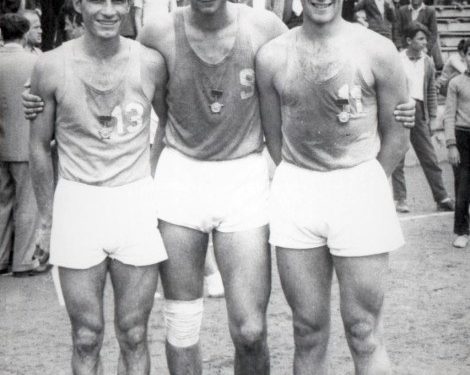

Memorie.al / Who wouldn’t want to return to those years of the last century, to recall the impressive and historical panorama-memory, the distinguished elite of Albanian sports, those who made the history of Albanian football, the legendary footballers and heroes of their time, who, with intelligence, passion, talent, and professionalism, managed to write history at the national, European, and global levels. Some of them rest in eternal peace, some are still here today – noble and proud, idols and legends – they are and will remain major figures, not only for the generation they belonged to and the future, but also for those dreamers, the young athletes, who wish to emulate those who made the era! Among them is the legend, the icon of Korça and Albanian football – the unsurpassable Teodor Vaso – a dominant sports figure in national and international matches, who brought fame and history to a more professional, spectacular, historical, and mythical football of the last century!

Continued from the previous issue…

Mr. Vaso, how were your relations when you won or lost against the opposing team? Was there any lingering resentment?

The question seeks characteristics of education, culture, and also the ethical substance of the games from a past era. Then and now, two factors influence the ethical purity of sports games: first, the education and culture of the players who make up the teams, and second, the discipline of sporting actions in the game and its surrounding environment. This factor is conditioned by the enforcement of sports regulations and the legal obligations applied by the state for incident-free and non-violent conduct during matches. Players, the team staff, the FSHF (Albanian Football Federation), referees, and law enforcement agencies for maintaining order, in various ways and forms, separately and jointly, according to their functions and duties, either create proper conditions or cause problems during matches.

Player-to-player and player-to-coach relations, both during and outside the game, were, with rare exceptions, correct. They not only created situations of honest sporting competition but also conveyed educational messages to the public about friendship between clubs and cities. Sporting rivalry on the pitch sometimes strained the relationship between players who were brothers, friends, or buddies. The bonds were, to a considerable extent, so sincere and natural that they fostered family friendships that we still maintain today.

In the function of the “foursome” at that time, besides the work of sports bodies in ensuring the smooth running of matches, the state was also involved, sometimes taking drastic measures in special situations. In the National Championship of the 1966–’67 football year, for unsporting behavior (labeled as “foreign manifestations,” as it was called at the time) during the “17 Nëntori” – “Partizani” match, both teams were penalized. As a result, “17 Nëntori,” which was heading towards securing the champion title, lost it, and the “Dinamo” team of Tirana was declared champion.

You also traveled abroad at that time. This means you saw countries with developed democracies, at a time when the Albanian people were isolated from the Western world. What did you think of Albania at that time? Did you notice the difference?

I think it is more favorable to convey the impression as I lived it, without flowery language. The Westerners (for clubs) first came to Albania from Scandinavian countries in 1962 – it was “Norrköping” of Sweden. Two years later, in 1964, the Germans of “Cologne” (Federal Republic of Germany) arrived in Tirana along with their complete kitchen. The news caused confusion in the government. The Minister of Defense at the time, Lieutenant-General Beqir Balluku, one of the leaders of the Albanian state’s high dome, gave an urgent order to the management of the “Dajti” hotel: nothing should be missing from the German team’s menu.

“If the ‘Dajti’ kitchen doesn’t have it, the order must be fulfilled by sending the government plane to Italy,” he had ordered. The kitchen of the “Dajti” hotel restaurant was comparable to European establishments because foreigners residing in or passing through Albania also stayed there. The information about the life of the people created worrying impressions, especially concerning the treatment of a champion team that required special conditions.

Based on this debatable opinion, the Germans of “Cologne” came to Tirana with a luggage of food to cover the team’s needs until their departure, and with assortments that were indeed missing from the Albanian market at the time. The Deputy Prime Minister’s concerned order was metaphorical, intended to alarm: “Even if the Germans ask for swallows’ milk, bring it from Italy!” As true as this event is, it is equally true that the conditions (with minor exceptions) of the Hotel “Dajti” (and the kitchen) were super-class.

They created a noticeable difference not only from the Albanian family kitchen life but also from the best establishments of the time, called Hotel Turizmi. At the impressive banquet held inside the “Dajti” hotel after the match that evening, a small group from the Opera and Ballet Theater performed, with the participation of singer Xhoni Athanas. The President of the “Cologne” Club expressed at that impressive banquet: “We are very pleased with your hospitality! Therefore, I ask myself if we will be able to respond so well to your hospitality in Germany.” Of course, his speech was overly modest, and the compliment was perhaps a result of the unsettling opinion they had heard before leaving for the land of eagles. On September 12, 1964, the only sports newspaper, “Sporti Popullor,” wrote about the “Partizani” – “Cologne” matches (0–0).

The result in Tirana kept our hopes alive. We prepared and set off for Western Europe, which was the first trip for a club team after the match “Partizani” played in Sweden, one of the Scandinavian countries. We were entering German territory by air. The plane approached Cologne from a short distance. On the Brussels–Cologne route, below us, two fiery threads moved towards each other. From above, those two extended and shining threads offered a fabulous beauty. We had only seen such sights in movies. The plane seemed reluctant to land in the city. It flew smoothly towards the airport.

It made you think that someone had ordered it to descend slowly so that the passengers could gaze at the city in the west of the FRG, near the Belgian border. Now, the whole Western World was before us. The evening was very beautiful. Cologne from above, with a wonderful, fairy-tale beauty, was mesmerizing. Famous Germany, the Nazi Germany of World War II, the State that became the terror of Europe and beyond, the famous country of the Aryan race, unfolded before our eyes under the glitter of the lights. We were seeing a capitalist civilization. A week later, I returned to my city.

I received word that the famous doctor, Sotir Polena, who had become a myth for saving the city from a German reprisal during World War II as they were leaving Korçë, was looking for me. In the doctor’s crowded room, Dr. Polena asked me: “Vaso, how did Germany look to you? Did you have to put on bulletproof vests? Capitalist Germany!” “No, no,” I understood, doctor, you are not asking about production relations.” He smiled and said: “The City!! When I was studying in Austria, we used to go there on weekends for holidays!”

So, what impressed and surprised me was that, 20 years after the war, the Germans had built a miracle upon the ruins in a very short time. 80% of the city was bombed by Allied aviation. Only 20% – distinguishable churches, hospitals, and schools – remained. Coming from a country like ours, where the night lighting was single-colored, the mesmerizing sight of the multi-colored illumination of Western cities at night was bewildering; a river of cars and crowds of people on the sidewalks hurried towards the Cologne stadium, which was filled with over 50,000 spectators. We traveled to the city center.

Beautiful women and girls, faces with tanned skin, designer clothes, polished shoes. Looking out the bus window, I meditated as I saw modern qualities: not only the clothes, the hair fashion, the pins, the glasses, the earrings, the bags, the laces, the belts, the bracelets, the shapes, the colors, the styles—there, I saw the luxurious and modern difference from ours. Here and there, glances catching the Red and Black flag on the bus window sent greetings: “Partizan – Tirana.” There were many Albanians from different regions of Albania.

Was the State Security (Sigurimi) surveilling you? How free were you to leave the hotel?

The more you contest and criticize that which aligns with the desires and interests of the interested party’s affiliation, the more you are right and realistic, just as the other affiliation considers the contestation unfair, dislikes it, and perhaps hates you. The answer’s accuracy lies in two truths. The complete truth is known only by those who organized those works. Second, those who were witnesses can only tell what they experienced. I am one of them.

In all matches outside Albania, the football teams’ Deputy Chief was a State Security officer, and this was known to all team members. Informers and other persons with special duties at all times and everywhere are never present. The football team was not guarded, nor could it be guarded from within, in the sense of protecting all team members, because it is practically impossible. The players’ movements, with the exception of fulfilling the team’s program, were never monolithic.

There was only this instruction: “Never go out alone, but with more than two friends, because big cities have problems, and there may be unexpected events. When you meet different people, especially Albanians, you must know their origin, because you might be compromised unintentionally.” Those who know the matter well are fully aware that such surveillance is done by people outside the team, whom the state had or has on duty outside its country. – How free were we to leave the hotel..?

In the FRG, in 1971, during the Germany – Albania match, I was accompanied by an Albanian gentleman who had fled Albania in 1950, Mysledin Glina from Korçë, who lived in Germany. He himself recounted this event after 1990 in Korçë. He made his story clear to me only on the last day, before we parted. No one questioned me; no one gave any indication about that story.

When I reported the incident to the Security officer, he told me; “These kinds of stories are common,” because the person knew very well that if he told the truth from the beginning, you would not accompany him, and he would lose the opportunity to talk to a Korça native like himself. How close one can get to the topic, I don’t know, but for the curiosity of the readers, I will say: three players have fled from the football teams: two players, Bahri Kavaja and (Muhamet) Bule Vathi, left the team in 1950 via the Dardanelles in Turkey, and Qemal Vogli from the “Dinamo” team in 1956 in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Do you follow developments in Albanian sport? What can you tell us about football in Albania today? And what can you tell us about the “Skënderbeu” team?

The regression of sport in Albania is more visible and more noticeable compared to the difference from the time before 1990. This refers to the relationship between the development and the shortcomings that arose compared to the sport of the time we left behind. The phenomenon is in two aspects: quality and mass participation. In terms of quality, the three glorious football teams of the capital can no longer be compared to their former quality, but in a very visible regression, so are the two former elite teams – “Vllaznia” and “Flamurtari” – which are far from their former greatness.

For other sports, it is enough to cite the condition of the handball teams of Skënderbeu of Korçë, which are not only incomparable but do not even come close to the brilliance of the games of the years before 1990. The greatest, most worrying misfortune continues with several other sports that no longer exist in many large and important cities in Albania such as Korçë, Elbasan, Vlorë, Shkodër, Durrës, Fier, where even if some of them have teams for heavy sports or athletics, others have none at all, like wrestling, cycling, gymnastics, chess, shooting, ping-pong, etc.

For example, they have been wiped out as sports in Korçë. Philosophy has many maxims to clarify the essence of an issue or problem. It says: two truths do not exclude each other, or even when there are more and when they refer to the same issue. Today, footballers have more jerseys, shoes, footballs, which are more beautiful, stronger, and professional, and they have more modern conditions in sports facilities. In our country, football teams also have a small number of artificial turf fields, which are of higher quality than the fields of the past.

But precisely with all these truths and several others, the modern and highly successful coach, Mourinho, stated in the media with the explosive phrase: “Football today is not emotional, because footballers play for money.” Above, we cited the productive truths of the time, but at the same time, there are many shortcomings. Many other teams train on fields worse than 50 years ago, so there can be no quality with a majority of low-grade quality when the majority trains in poor conditions. The talented element is reduced because a large number of children do not undergo professional training as they lack the financial means to pay for training and travel with the team. For all of football in Albania, to this day, I state: I do not like today’s Albanian football.

Of course, the expression does not fully address the entire content of today’s football, so I would specify: Our football today has more shortcomings in relation to the time it lives in, so in this conception, to fully convey the idea, I must recall the title of an article I published some time ago in the press, entitled: “The Albanian Football Factory is Obsolete.”

If we speak more concretely, we must remember that in many of our club teams, training sessions are outdated, not figuratively. The training methods are empirical, which is not based on scientific theoretical requirements. For example, there is a lack of physical-technical testing, physiological measurements during training and matches, and muscular strength training, etc. I do not like today’s football because it is second-category football (with the old designations, first-category).

About 200 Albanian footballers trained in our teams play outside Albania; if they were here, we could have a first-category championship with 10 teams of 20 players each. In the written press, there are few or no analytical writings interpreted with contemporary football indicators. This situation and phenomenon constitute an atrophy of professional analyses, which leaves the development of current football to spontaneity.

The great evil lies in the fact that at that time, some of these requirements were functional, which is why, despite the material deficits of that time, our national team drew with a brilliant game against the world champions, the FRG, and eliminated them with a more than equal performance. This reference point has extraordinary value when, in the years we are living, we cannot measure up to a small country like Iceland. A dream from the “antiquity” of football in Albania (78 years ago).

In endless anticipation since 1933, to climb to the top of the Albanian teams, the second “Skënderbeu” (because the first was champion in 1933) won the National Championship title again in 2011. It had dreamed, fought, protested, rivaled, but it would take over three-quarters of a century to climb where it believed it deserved.

“L’argent fait tout, l’argent fait la guerre” (Money does everything, money even makes war) – is an old French saying. The “Skënderbeu” team (the second one), from its first champion title (2011), was financed by a board of financiers who created the highest possibilities for the team compared to other teams in Albania to compete in Albanian football, led by President Agim Zeqo, and now with the other President, Ardian Takaj. / Memorie.al