By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part four

SPAÇI

– The Grave of the Living –

Tirana, 2018

(My own and others’ memoirs)

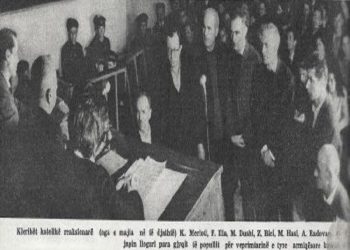

Memorie.al / Now in my old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of the others whom the regime silenced and buried in unnamed graves? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was only accidentally present, although I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you have only two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days, I would not want to take to my grave.

Continuation from the previous issue

God, oh God, what an abyss!

A reddish, bare mountain, perhaps from the corrosion of the pyrite concentrate or a curse from God-I don’t know what to call it-was enclosed with fences. The slope at the upper edge was about forty-five degrees, while at the bottom edge, it rolled off sheerly (like a knife).

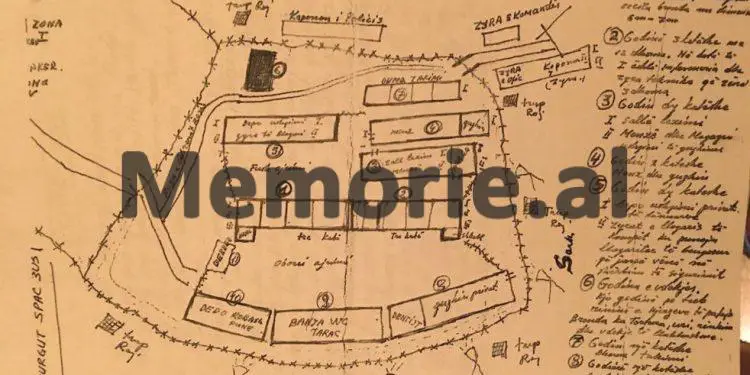

They had carved terraces into the steep slope, forming several levels that diminished from top to bottom. In the five thousand square-meter space, they had installed everything: from the command offices and the barracks for soldiers and police, the mess hall for the service personnel, halls for political education, descending to the cells, the communal barracks, the kitchen, the shop, the technical office, the private kitchen, the water taps, and finally, the latrines.

I will present the planimetry according to the visual order, starting from the top.

Beside the road that climbed to the mine, the camp-prison command building towered. A few meters further were the soldiers’ barracks, behind them the kennels for the sniffing dogs, and the latrines for the military personnel. On the second level, two meters below the first plane, was the camp’s entrance gate. Beside it was a mini-building, three by three, which served as a shelter for the duty officer and, simultaneously, a checkpoint for food and for family members when they came to visit.

The terrace, three to six meters wide, stretched from the special meeting room for special people and ended at the isolation cells.

A slight gradient led down to the third level, where they had improvised a gate leading into the camp via some small steps dug directly into the ground. To the right of the entrance stood a small shed compared to the others, but better ventilated. Opposite it were the communal kitchen and a small room, which was sometimes used as a listening post by the operative and sometimes as a torture room by the service police.

On a wooden pillar, next to the slaughterhouse-cell, the loudspeaker howled, eating away at our lives with military and funeral marches, with dithyrambs for the Party and the leaders of global communism, with parodies that crushed imperialists-revisionists, but hitting its peak with the ominous speeches of the vampire Enver.

The fourth level was the most spacious area in the entire territory (as I would later learn from a friend from Mirdita, this little piece had been a field). To the right, two structures rose, one long and one wide, forming an “L” profile. The square in front of them served for roll call, as a hand-game corner, a piazza for the unemployed to walk, and as purgatory for washing and cleansing the “sins” of any rebellious prisoner, whenever the commander felt like it.

This square had acquired the status of a “place d’armes” for re-arrests, where the district prosecutor demonstrated force and the commissar displayed “knowledge”- that is, a kind of modern “Golgotha.” To the left were lined up the “residence,” or the clinic of Met Karakashi, the longest-serving dentist in the prisons, followed by Ndoja’s shop, beside it the food and clothing depot, in the middle the Kosovrast hospital, and ending at the edge with Bozo’s laundry room, a Montenegrin-Bosniak homosexual.

On the dividing line between the fourth and fifth levels, they had erected two glass display boards, advertising news, quotes, and maxims from Marxists and the executioner Enver. During the Spaç revolt, the prisoners tore them down with pickaxe handles and vented their anti-communist fury by setting them on fire.

To the right of the fifth level rose the barracks above the abyss where they sheltered me, beside it the barbershop of the big-nosed man from Mallakastra, and a minor space for the counting chute. To the left were the showers, the private kitchen, and the blacksmith’s shop, as well as a compartment further on, the use of which I never fully grasped; whispers spoke of perverse activities by the head of the technical office, Medi Noku, with the lackeys who followed him.

On the sixth and final level, they had installed the latrines, next to the taps with the reddish basin, and immediately below them were the “no-go” signs; the enclosure with barbed wire began, beyond which were the watchtowers. I want to emphasize that the slope in this position was dizzying; if you lost your balance, you would fall headlong.

At the bottom of the slope, the waters of the stream gurgled in winter, descending from the heights of Munella, while in summer the currents turned reddish. Over it hung a steel cable bridge that connected the slope with the path that snaked alongside the perimeter until it met the main road.

In the final corner, between the “L” barracks and the one over the abyss, a perpendicular path cut downwards, beside the torrent that discharged the gallery waters into the collector stream. Right there began the ordeal that led to the labor camp.

The entire territory, excluding the command offices and the soldiers’ barracks, was surrounded by multiple fences. A guard post rose every thirty meters, but in the most dangerous positions, the watchtowers were twenty meters apart, and where the possibility of escape was judged high, they had a triple perimeter fence.

The place was desolate; besides two or three acacia trees next to my barracks and some flowers cultivated by Mihal Cerja, the agronomist shule, you saw no other greenery. Above us hung a patch of sky, as if torn from the atmosphere and trapped in the coils of the barbed wire.

In winter, the sun barely grazed the lips of the bottomless pit, while in summer an invisible scorching heat practically suffocated you.

The layout I found when I arrived remained the same over the years, except for the three-story building on the fourth level, after they demolished the “V” barracks and a building with a concrete terrace and a pair of stairs in the middle, which they installed supposedly for showers, but in fact created a wider enclosure for counting.

This change belongs to the later period; many waters would flow and many events would occur until then. To complete the contours of hell, presenting only the layout of the sleeping camp, where misery was conceived and finalized, is not enough; we must also describe the kingdom of Hades, the underground hell which, on a macro view, presented the ordeal where torments were materialized, because in those holes, the contest between the slave and the devil was for the continuation or interruption of life.

I invite you to imagine two mountain faces of enormous dimensions, which the creator, in a fit of rage, had symmetrically divided with a single slash. At the bottom, the stream, originating from the heights of Munella and Kalimash, snaked and flowed into the Fan River, opposite Reps. To the left, the perimeter enclosed the hill territory, with guard posts scattered up to the highest point.

The hundreds of hectares with a dizzying slope had been divided into three zones (after my release I learned they had added another one, and later yet another, but this belongs to the new era). The division into zones represented the statistics of the administrative unit and distinguished between the copper and pyrite mines.

When you passed the gate, you were faced with the uphill climb that wound beside the torrent, through the steps carved into the tuff rock, ran along the inner perimeter, and joined the main road. The path that connected to the highway, where trucks circulated bringing armaments and carrying ore to the enrichment factories in Reps, Rubik, or Laç, was covered in yellow dust in summer and treacherous frost in winter.

The first zone started right above the axis and included the holes that extended horizontally into the belly of the mountain; rarely did you encounter a front with vertical shafts (fumela) and shallow pits. Copper ore was extracted from these mines. Although water flowed winter and summer, they were somewhat better maintained and had slightly more comfortable conditions. Since they were located near the camp, the elderly and the less problematic contingent worked there.

About two hundred meters higher, the holes of the third zone opened. They also stretched horizontally into the depths of the mountain, but there were also vertical shafts. Copper ore was extracted there, but in some side pockets, you would encounter some mixed ore. They snaked beneath the surface, and the risk was much higher because the rocks were crumbly. At the very end, you found some neglected mines, perhaps not very rich, which they saved for difficult times.

The inmates who were slightly more balanced, but still with subversive ideas and without any early hope of rehabilitation, were often sent to the galleries of this zone.

The second zone started after a visible but mostly imaginary groove, as the hill jutted out like a turtle shell and disoriented the view. This hump resembled the balcony from which one could observe the funnel of V-Spaç and was the only artery that connected us to the world of the living. To the northeast of the celestial tunnel, the eye peered hill after hill until it was lost in the boundaries between Mirdita and Kukës.

The galleries in that zone extended chaotically. No one could guess which direction they might take, as the direction could change after every meter due to unforeseen collapses. They could go straight, cut sideways to the left or right, or up, or down. They advanced haphazardly and according to the whims of chance. The galleries did not cut deep, but being irregular and unsafe for life, they created large chasms whose tops were invisible.

This zone had quality ore, even near the surface. Temperatures in the winter cold reached thirty-five to forty degrees Celsius, perhaps even more, so much that you couldn’t resist without stripping naked, while in the summer heat, you had to wear winter clothes to protect yourself from pleurisy. A concentrated sulfuric acid solution dripped from the ceilings, turning clothes into camouflage wear, and when it acted deep down, into scarecrow rags.

Pyrite somewhat resembles sandy or tuff-sandy rocks and weighs heavily. Ismet Boletini equated one shovel of ore to almost twenty-five kilograms, while a wagon to two to three tons. Even if you discounted his sarcasm, the truth remained approximate: “The pluses and minuses are related to quality; the rich one is heavier, and the poor one is lighter,” he explained.

Let’s continue, since Ismet-style calculations have nothing to do with the topic.

Besides its specific weight and abundance, pyrite darkens the skin. When you emerged from the mine mouth after eight hours, you resembled an Afro-Ecuadorian, so much so that your mother would hardly recognize you. Your teeth and eyeballs shone so white you might think you were in the heart of Africa, in Ghana or Gabon.

Due to these qualities, they considered it the “experimental reserve” or “prison within a prison,” a kind of internal exile for punishing the disobedient who showed no signs of political improvement. Thus, the residence of Hades resembled the ninth circle where Dante housed the sinners.

Meanwhile, Purgatory also existed…!

In addition to the mines, auxiliary sectors operated within the fenced territory, such as: the workshop for repairing hammers and wagons, the electro-hydraulic brigade, the warehouses for clothing, tools, and carbide, the inclined plane depots where the ore extracted from the mines was deposited and loaded onto trucks that transported it to its destination; the track-layers and ventilation pipe workers, who, although working underground, made preparations outside, but also the ‘tekahytët’ (manual laborers) for clearing roads of rocks and dirt, or from the snow that blocked them in winter.

Genuine specialists whose need was felt worked in these brigades, along with the sick who had stacks of medical reports, who were squeezed dry and then exiled to other prisons to die, or the relatives of the operative, the “scoundrels” of Medi Noku, and his flatterers.

They had surrounded the entire plateau with fences, over three meters high. On top of the pillars, they had tied a lamp, and every fifty meters, a floodlight – in places where the streams meandered and intersected with the collector stream, there were two floodlights in opposite directions. At the same distance, watchtowers rose where fully armed soldiers stood guard.

In problematic positions, where the possibility of escape remained evident, they were placed directly opposite each other, no more than ten meters apart.

The distance to the command post was exhausting; to reach the far end, the soldiers had to endure Pindaric marches. Thus, they stationed intermediate sub-units to shorten the distances. They had built some dilapidated barracks around the mountain where the soldiers slept.

However, this differentiated treatment had increased dissatisfaction and fueled quarrels within the ranks of the personnel guarding us. Those who had been assigned far from the center envied their colleagues whom fate or a friend had helped serve near the command. Consequently, those far away considered they discriminated against, and their comrades privileged.

Therefore, the phenomenon of jealousy and excessive zeal for taking a comrade’s place unwittingly arose, which the command also stimulated. In the fervor of zeal, everyone was vigilant in protecting their respective sector, to the point of shooting idly at the inmates carrying things far from the “no-go” signs, causing unnecessary casualties. This chaos forced the superiors to caution them about the use of weapons outside legal conditions, even though there were no consequences, as no one held nominal responsibility.

Amidst the surge of ambition, a colleague would set a trap for another to take his place. Characters degenerated in that faith, so much so that the personnel wallowed in the mire of spying and pimping. When an escape attempt proved successful, a colleague would rub his hands over the disaster that befell his peer and rejoiced at the chance that knocked on his door.

When a man from Dibra broke through hell and managed to get outside the perimeter, even though only for two days, a storm broke over the military unit. The entire command chain fell; even the simple personnel were no longer seen in their former guard posts. Some were exiled to the furthest points, cursing Myftari for the calamity he caused, while others who were brought closer congratulated Myftari for the daring act.

The relief did not present any impressive panorama. Although I spent three years there, I never managed to see the village of Spaç, except for a building on the opposite hill and some houses at the entrance of the gorge.

Two barren slopes, with a stream at the bottom, faced each other. The peaks, almost equal, fell perpendicularly toward the stream that snaked between the bare hills and disappeared right after a bend, not far from the camp.

There were only two seasons: a long winter and a dry summer. Autumn was barely noticeable; the trees were stripped, and it passed like lightning, immediately dissolving into an extremely harsh winter. In the cold months, even on the nicest day, the sun rarely met those gloomy places, and the rays only shone for about three hours.

Winter lasted over half a year. The temperature dropped twenty degrees below zero; it snowed, it froze, and the biting winds sheared the tops of the trees. The depth and turbulence twisted the skeletal bushes and eroded the reddish tuff rock./Memorie.al