By Roland Sejko

Memorie.al / No genuine study existed on the presence of Albanians in the Italian military forces during the Fascist period until the scholar Piero Crociani, more passionate about uniforms than historical analysis, set to work cataloging all the data on this issue. The result was a 400-page book, filled with facts, documents, and photographs, which highlight a difficult relationship between Albanians and the fascist uniform.

From the Royal Guard, a futile decoration for Albanians at the Quirinale after the union, to the mass desertion of the troops of the Albanian “Tomori” battalion during the Italo-Greek War, Crociani speaks about the “Albanian World.”

Mr. Crociani, given that the Italians knew the geo-physical situation of Albania well, and the Albanian army had been prepared by the Italians themselves, was the invasion of Albania something conceived and improvised within a few days?

Although plans existed 40 years prior, when Albania was still under Turkish rule, the Italian landing of ’39 was practically improvised, planned in just a few days. There are notes left by General Pariani, located in the Museum of the Risorgimento in Milan, where there is a note in red pencil, in beautiful handwriting, saying: “It doesn’t matter how, we must do it as quickly as possible.”

From a military standpoint, it was not a difficult operation because we had bought their army. But above all, it did not turn out as it should have because it was organized terribly poorly. Some soldiers participated who did not know how to ride a bicycle or motorcycle, or some engineers who were unfamiliar with the new radio equipment. So, it was improvised.

Immediately after the invasion, the two armies-Italian and Albanian-merged into one. What was the reason for this fusion?

Yes, a single army was formed from the Albanian and Italian armies. There was no other way, but for practical reasons, some exclusively Albanian units were left: 6 infantry battalions, 2 anti-aircraft machine gunners, in addition to the Royal Guard battalion, while other units, such as the Carabinieri, etc., were mixed, Albanian and Italian.

One of the most interesting corps was the Albanian Royal Guard, which later transformed into the Royal Guard…?

The Royal Guard was an Honor Guard unit and had no other duty. It was brought to Rome for decoration and was never engaged in war. In Rome, it had to be visibly shown to everyone that the King of Italy was also the King of Albania. It was for embellishment, or rather for façade, and never did anything. They were in service until ’43, and then an overwhelming majority returned to Albania after September 8, when Italy capitulated, coming here along with the Germans.

How many Albanian soldiers were included in the Italian Armed Forces?

There were about 10,000 in total, but it varied in different periods. In the period 1941-’42, for example, there were fewer soldiers but more volunteer militia battalions.

Of these, only a portion was engaged in the military campaign against Greece, and there were a total of 2,500 deserters out of about 10,000 Albanians in total. A special law even had to be passed for this, and they were released as a punitive measure.

What was the relationship between Albanian and Italian soldiers in the same unit? What was the climate or cooperation like between them?

I cannot answer, because Italian soldiers have not written memoirs or impressions on this issue. I remember that my father was the commander of an Albanian unit, but I cannot say that he told interesting things in this regard. His memories mostly concerned life in the army; he talked about taking sheep to eat when they went through villages.

Were there Albanian officers among the soldiers trained in Italian academies?

Albanian officers, especially the younger ones, had graduated from military academies, even from the Nunziatella military school, or from Milan or Rome, in Italian schools, from the Turin Academy, or the Modena Military School. There were others who had studied in Albanian military schools, while the older ones even came from the Ottoman Army, so they had different skills, customs, and other life systems. Theoretically, cooperation could have been easy, but it really wasn’t.

For what reason?

Because, in any case, they were very different. Initially, the Albanian battalions were commanded by Albanians, but then in the years ’40-’41, they were included in larger Italian units, where even though entire Albanian brigades were formed, the officers were all Italian.

Did the Italian army really need these soldiers in its corps, or was it more a matter of propaganda?

For the War with Greece, the Albanian army was not needed at all. But Mussolini himself said in one of his speeches: “We don’t need them, but they must be in the army, to show that we have them, and that they are with us.” It was necessary to show that those covered by the Italian flag should serve for the Italian flag, like the Libyans, Albanians, or Ethiopians; whether by mandatory or voluntary service, the regime considered it natural for them to participate.

Why did they desert?

Because it was not their war. They did not feel that the war with Greece belonged to them too. They were more engaged in Yugoslavia. Especially in Yugoslavia, I would say, they were ready as irregular troops in the Shkodra area, and they fought quite well. It seemed they felt something there, but against the Greeks, not at all. Perhaps the Italians created false illusions about the desire of Albanians to fight. The use of Albanian battalions in the early days was a complete bluff.

Perhaps they were not accustomed to a kind of fighting that was perhaps too complicated for them, with planes, cannons, tanks. Meanwhile, the Albanians were very good infantry troops for guerrilla warfare, as was seen later in April ’41 in Yugoslavia, where the Albanians really excelled.

Some officers trained at the Turin Academy are said to have attempted an assassination of Mussolini. How did that event happen?

A month before the invasion, in Turin in March 1939, there was a serious plot among the Academy students that was never put into practice. Foreseeing the invasion of Albania, they had planned to assassinate Mussolini, who was going to Turin in May of that year. They spoke among themselves, decided who would be the shooter, but this boy backed out, and the organizer of this plot, Ismail Karapici, said he would take it upon himself.

He went to Albania where he got stuck during the invasion, returned for the end of the school year, but the news had spread in Albania, and from Albania, the notification arrived in Italy that an assassination attempt on Mussolini had been planned during his visit to Turin, by some Albanians. Albanians in Turin at that time were very few, either Academy or Polytechnic students. Before Mussolini’s visit, the Albanians pretended to be happy, while the Italians pretended not to trust them.

A scandal could not be caused, so all Albanian soldiers who were in Italy were concentrated in Rome for the oath. It was a bit difficult for the Polytechnic students because they were free citizens, but a trick was found for them too; by the Chief of Police, they were all sent on a social excursion to Tripoli, to see how the Muslims of Italy lived, and naturally, everyone left with great pleasure.

But the circle was closing, and the responsible parties were found. Everyone tried to deny, justifying themselves in every way. The only one who accepted and took all responsibility was Ismail Karapici.

This was a case that should have been subjected to the Special Tribunal for the Defense of the State. Just planning the assassination could have resulted in the death penalty. But the idea had to be given that Albanians were enthusiastic about the regime, and therefore it was decided to resolve it administratively. They were sent to Albania, to the internment commission, and received a sentence. Karapici received 7 years of internment, while the others received lighter sentences.

Karapici is a very interesting figure. I cannot understand how it is possible that he was not made a “National Hero” in Albania…?! I have evidence that until 1945, he was on the Tremiti Islands, because I have a letter where he was asking for a pair of shoes. Since the Tremiti Islands were not bombed until the spring of ’43, I think he stayed there, and then went to Albania.

I thought he might have gone to the wrong side and been eliminated for it. Recently, they told me his story. He had presented himself to the English in Puglia, and when the English commandos went to Santi Quaranta (Saranda), where they were blocked by Enver Hoxha’s partisans, he went with them to serve as a translator.

After a few days, he was invited to go and meet his family. Since then, his traces have been lost. Maybe he was killed that same evening. This, then, is the story of a missing national hero, and I am very pleased that I found his story, because it is important that he is known in Albania.

Among the students of Nunziatella was one who would become an important figure in the history of Albania, Mehmet Shehu.

Yes, in the early ’30s, Mehmet Shehu studied at the Nunziatella School, and then I believe they discovered he was a communist and pursued him to Albania. I don’t know if this is the official version, but I know that something was wrong with him and he was expelled.

How did Italian officers perceive the presence of Albanians in their ranks?

Documents exist where the list of officers is written, with the evaluation next to it, much worse than one might imagine; there is a lot of prejudice, except for the youngest ones. In general, there is no appreciation for them. “True Turkish exemplary,” “Pure Muslim” was written…! So, things are not at all positive! There was a lot of prejudice, but it must also be said that the Albanian army in the ’30s was not at all modern.

It was an army formed on the basis of loyalty to the King, and loyalty to the King meant having been born in the Mat area, or being related to the King. Career in the Albanian Armed Forces was very much linked to this concept.

One of the military corps was the Albanian Royal Guard, which later transformed into the Royal Guard…?

The Royal Guard was an Honor Guard unit and had no other duty. It was brought to Rome for decoration and was never engaged in war. In Rome, it had to be visibly shown to everyone that the King of Italy was also the King of Albania. It was for embellishment, and never did anything. It was in service until 1943, and then an overwhelming majority returned to Albania after September 8, with the Germans.

Was their uniform chosen to highlight the traditional Albanian elements?

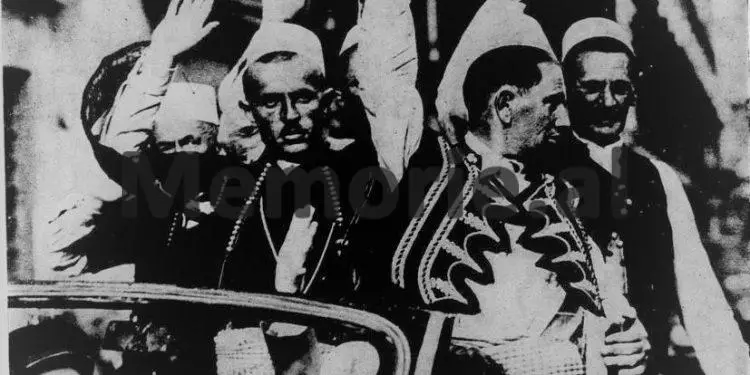

The uniform of the Royal Guard theoretically imitated the traditional costumes of the Ghegs and Tosks, so there was one unit with the fustanella, typical of Southern Albania, and another with brekushe (baggy trousers), like those of Northern Albania. They wore white qeleshe (skullcaps) on their heads, covered with black cloaks.

They were very decorative. The others dressed like Italians, differing only in the stars and the helmet, where Skanderbeg’s helmet was engraved. Then, when the Carabinieri were replaced by the gendarmerie, the latter dressed like Zog’s old gendarmerie.

Mussolini wanted to see both types of uniforms, but everything was quickly arranged for the May 9 parade. The uniforms were brought quickly; the soldiers were dressed and sworn in quickly. And they were ready. One of the battalions was planned to go to Tirana as well.

They took a trip to the Alps in 1940 but came later, when everything was over, and stayed in Rome. They never moved from Rome, so I believe they spent the war in the most peaceful way possible.

But it was very difficult to maintain the unit’s number because at that time it was very difficult to bring Albanians to Italy. At that time, those who were supposed to serve in the Royal Guard, after arriving at the port of Durrës, would leave and decide to return to their homes.

After September 8, what happened to the Albanians?

From the end of ’42, when things were not going well for the Axis countries, a flow of desertions began; soldiers deserted like a river, one after the other. In 1943, we released the regiments; 2-3 regiments of Albanian Infantry were released because hundreds of them had deserted overnight.

We had received orders to remove the ammunition, before which they had deserted en masse, and then, in Italian uniforms, they had attacked our barracks. On the other hand, there were also some unfortunate ones who were captured and shot.

We could not even recruit young people, because that would require new weapons, and there was also the risk that our weapons, through them, could fall into the hands of the partisans. In the summer of 1943, the Gjirokastra Police Headquarters was under the control of the partisans.

Among those who stayed in Italy, do you recall any important names?

Important as a personality, no. But it is interesting, for example, that among them was the brother of Mother Teresa of Calcutta, an artillery officer who died years later in Sicily. Some continued to work in the military; others started a new life as civilians.

I also know someone, a wonderful man, who refused to seek Italian citizenship because, even though he was an officer and had gone to Russia, he felt he was Albanian, so he stayed as a refugee. Memorie.al