By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part fifty-two

Memorie.al / I were born on 23.12.1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the ignorant investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Internal Affairs Branch in Shkodër, split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, after breaking several ribs, half of my molar teeth, and the thumb of my left hand, on October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the wretch Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After cutting my sentence in half because I was still a minor, sixteen years old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the Rrëps political camp, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the political prisoners’ revolt, four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a process that is perfectly normal in the democracy we claim to have. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Rilindas” (Renaissance) Government sent Order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for; The dismissal of a police employee. So, Divine Providence was intertwined with the neo-communist “Rilindas” Providence, and precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced, no more and no less, by the former operative of the Burrel Prison Security. What could be more significant than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

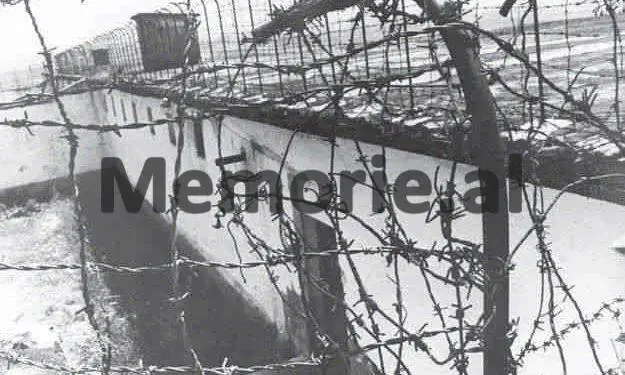

RREPSI

(Forced labor camp)

Memoir

The First Meeting

(The boat sunk in the swamp)

“Since more than one family member could end up in prison at once, they separated them too, one in one corner, the other at the most extreme edge. Thus, new obstacles arose for the family members; to keep them supplied with food and clothing, more sacrifices, more time, more people, and more monetary income were now needed. This ‘brotherly’ aid, of the Serbian UDBA agents, was called organization. Now we will talk about how the term ‘reorganization’ was born in prisons. What I spoke about above was only the genesis of this process.

Because the experience gained over the years from their former comrades-in-arms, now mortal enemies, these State Security personnel applied it in practice. The pupils proved to be more agile and innovative; they far surpassed their professors. They further perfected the mechanism they had acquired and adapted it to the new conditions. With the establishment of labor camps, they organized groups of convicts from different districts, who were sent to these barbed-wire-fenced terrains to exploit their labor force for free.

Following the example of the Nazis, the camps were initially used for the fulfillment of the most necessary needs, so to speak, the first-hand ones. As a start, buildings were needed to house their guards; so, they built new residences. But since the prisoners became skilled in the trade and the executioners saw the benefit of the free labor, they continued the exploitative ritual further. The swamps and marshes had to be reclaimed, the Tiranë-Durrës railway had to be built, the aviation field in Urë-Vajgurore had to be modified, and a new airport near Tiranë was absolutely necessary so that the Great Leaders could approach the socialist camp; and yes, drainage and irrigation canals were needed in Vlashuk and Beden, etc., etc., and so on…!

And who better and cheaper than political prisoners could do these things?! Later, this unstoppable trend continued with factories and combines, with mines and palaces, until the regime was extinguished. The daily toil with extended hours, the exhausting journeys on foot, often more than two hours away from the sleeping barracks, loaded with tools on their backs; the pronounced lack of food, of clothing, over-exhaustion due to age, the lack of sanitary conditions, the contagious diseases that wreaked havoc; all these evils together forced the prisoners to increase solidarity among themselves.

Groups of convicts, after spending a long time together in a prison or camp, often even in a brigade or a barrack became very close friends; the wealthier helped the needier with some food; the stronger supported the elderly and the sick to meet the norm, to escape punishment. Group living encouraged cooperation, increased trust to such an extent that in narrow social circles, they even made escape plans, perhaps not all of them, but one, two, three, and the others who were aware of the act did not react, or moreover, contributed to the fulfillment of their fellow sufferer’s dream.

There had been escape attempts from time to time, although most of them failed: the tunnel of the Tiranë prison, in the early fifties, ended with the re-sentencing of a large group, with long terms; so much so that I would find three of the protagonists of that sensational event, Besim Latifi, Qani Mulita, and Zihni Dervishi, in Reps, we would spend five years together and, after I was released, they would still remain there! But some were successful, like the case of the aviation field in Berat, where an organized group escaped, supported even by comrades who had no intention of leaving, but who caused a commotion to give their fellow sufferers time to get as far away as possible from the pursuers.

This successful attempt, which ended with the escape abroad of some convicts, like Nezir Danushi, etc., and with the rest who joined the fighters in the mountains, for the overthrow of the communist system, (the Zhapokika revolt led by Kalem Plashniku and my friends, Baba Bajram Mahmutaj and Skënder Alia, who spent over thirty years in prison), gave an exemplary lesson to the heads of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the prison directors. From that time on, to increase surveillance over the groups that might be organized or even specific individuals who might slip out of their hands and think of escaping, they began to apply reorganization.

Although later, attempts to escape have not been lacking by individual adventurers or even limited groups, they have generally failed, either in prison, denounced by State Security informants, or even when they managed to leave the barbed wire enclosure, they were caught in the field by the Pursuit Forces or the armed groups of the Voluntary and territorial Forces; rarely did anyone manage to cross the state border. Thus, to break up the configurations of these groups or the close societies they considered almost as cliques, they occasionally applied reorganization. Reorganization could be extreme, meaning transfer from one camp to a prison or another camp and vice-versa, or partial, or specific reorganization.

In the case of extreme reorganization, when the convicts were separated, it was rare for them to meet again, because one ended up in the east, the other in the west. Whereas specific reorganization consisted simply in destroying the internal configurations in the barracks, in the brigades, at the work fronts, or it could only be done for a malicious mixing of elements, originating from different regions and with opposing political beliefs, so that they could not find a common language with each other, let alone entrust dangerous secrets to one another.

It often happened that two opponents shared the seventy-centimeter boundary, and even though the enmity between them was openly known, the command insisted and forced them to live together, side by side. In such cases, the two ‘enemies’ sometimes reconciled, brought their positions closer, and even sometimes became brothers in solemn pledge. This behavior left the petty organizers speechless. But there have also been tragic cases, when the close proximity ended in casualties and the organizers rubbed their hands with satisfaction, having achieved their goal. But when they applied specific reorganization, it sometimes happened that they brought a thief, a scoundrel, a spy, an immoral person, etc., to your side, according to the wishes and orientation of the camp operative.

You were forced to endure! To endure and to resist! Generally, when they prepared the reorganizations, they worked quietly. They processed the lists in complete secrecy, as if in illegality. A limited group of persons, loyal to the command, hid in the darkest corners of the Technical Office. But nevertheless, the news crossed the fine filters of secrecy, and through the short infrared waves of the prison radio, it spread. The head of the Technical Office, or the spies they invited to give opinions on individuals or groups that needed to be disbanded, had close and trusted friends who told them, and these had their own closest friends whom they informed, and thus, the bag was torn and the pot emitted an odor, before the news was even a fait accompli.

Regardless of the duration of the implementation, the rumor period was enough to mobilize friends and comrades, to establish new alliances, and when this reorganization was updated, the groups had been recreated and the sleeping places had been redefined again. Apart from the trouble caused by carrying belongings from one barrack to another, the social groups did not suffer much damage! I had been in Reps for about six months. Willingly or unwillingly, in that confined space, I had met most of the three hundred men who were serving their sentences there.

I got along well with my workmates, I got used to the hard bread and the rules. The winter frosts had now passed, and the weather was warming up. The spring indeed came late, with a lot of humidity, but as the weeks passed, the weather changed, the day lengthened, and the sun was quite warm. When we had the chance, we found a warm spot and sunbathed, to ward off rheumatism. But the longer the day became, the more our toils increased. Now the police were no longer satisfied with eight hours of work; thus, ten to twelve hours were spent at the construction site. Many physically exhausted and chronically ill convicts, who failed to meet the norm, ended up tied with wires to posts on the ‘Road of Golgotha.’

It had been almost a month since I heard whispers about an expected reorganization. I followed the reactions of the old men but they weren’t talking about it. So one day I couldn’t resist and asked my neighbor: ‘Uncle Esheref, I’ve heard talk high and low about reorganization!’ ‘I know, did you hear it too? Prison talk is like a monk’s farts, oh young one!’ he cut me off. ‘Maybe, but if it turns out to be true, it would ruin a lot of work for me!’ ‘Why, where you are now, were you supposed to get out of prison earlier?!’ nervous, he put down his small knife and blew with all his cheeks on the wood shavings he was carving.

‘No, but they would move me away from you!’ I said somewhat complainingly. ‘Come on, man, why are you acting like a child! Where are they going to take you, come on? Here, in this two-dunum plot, we will remain!’ He scattered the shavings and added: ‘They’re just going to change our lair! Well, summer is coming now, even animals change their nest!’ ‘Uncle, we are in prison, here!’ ‘So what?’ ‘I need friends!’ I answered dramatically. ‘Oh, you little guy, you are a professor now and we old-timers are no longer of use to you!’ I didn’t expect him to speak like this, although I understood that he did it just for show, because inside his soul spoke differently. Some time passed; I did not open this topic again, for fear that he might respond more harshly.

Then one evening I heard my two neighbors talking precisely about the topic I had been interested in a few days earlier. They thought I was asleep and were whispering. Nevertheless, I heard them clearly, even with my head under the blanket. Uncle Esheref: ‘Vask, have you heard about some movement in the camp?’ Vaska: ‘Yes, Sheref, it has been talked about for days and where there is a voice, there is something!’ Sheref: ‘I know they will do this, I know, because they haven’t done it for a long time, but I’m worried about the boy, we must find him a place!’ Vaska: ‘I spoke with Daut and Riza, they were also aware and told me they had talked with Zef, Mark, and some other comrades.’

Sheref: ‘This is a great misfortune, Vask!’ Vaska: ‘Whatever happens, we have a friend in every barrack.’ Sheref: ‘I know, they won’t abandon him! But we got used to this young one; he is like our own child!’ Vaska: ‘You are right, we don’t like them taking him away, but we are in prison, my friend!’ Sheref: ‘That’s right!’ Vaska: ‘The important thing is to arrange him near our friends!’ Sheref: ‘By my solemn promise, I will speak with Zef and Hafëz myself! Good night!’ ‘Good night!’ I followed the conversation with the pain of a son for his father, when he sees him in trouble. From that day, my love multiplied tenfold.

Until that time, I was still the youngest in age, consequently the most pampered by all the elders. Because I had devoted myself to my studies with passion, I also enjoyed the sympathy of the intellectuals, who helped me in every way. Despite the troubles that had befallen them, they found time to worry more about my fate than about their own shortcomings. Thank you! What was talked about for a long time happened very quickly? One Sunday, after the morning roll call, the order for reorganization was announced to us through the town crier.

Someone from the Technical Office read a long list of names, and then hung it on a glass stand. They had filled several pages, at the top of which they announced to all persons who found their name that they would be housed in x, or y barrack. Among others, my name was there too. I had to leave the place where I had been for months and be housed in barrack number one, which was the first building, to the left of the camp entrance. It was the barrack located on the terrace below the showers, the most unsuitable of all the others. The height of the eternit roof was level with the second terrace. In summer it was sweltering heat there, while in winter, the humidity took your breath away. They had christened this barrack with the scornful name, ‘Barrack of the Wrecks.’

Only when I settled in it did I understand the meaning of this nickname; they had gathered all the elderly and the sick of the camp there; there were few or no young people. I don’t know exactly if it was a coincidence or a calculated combination by others; how I ended up exactly in the place where my friend, Sulo Gorrica, had slept, who had been released a couple of months ago. I never found out the truth, but to be honest, I never bothered to find out; nevertheless, I made my bed in the vacated spot and from that day on, I became a registered resident of the first row of the ‘Barrack of the Wrecks.’ As soon as I got settled, I looked around. I was surrounded only by old men.

But what would make a special impression on me in the following days, when I got to know my new co-residents more closely, was the presence of almost all the clerics who were in Reps. I present them according to the order of their location: In the bed below, on the left side of the entrance, starting from the front of the barrack, were lined up in order: Father Zef Pllumi two places away from me, the big-mustached iballas Çun Mëhilli; next to him and me, another priest, Father Ernest Trashani; on the other side of my bed, a plump old man from Kolonjë; further another man from Kolonjë and very close to the door, the person in charge of the sleeping area Petrit Hoxha, a veterinarian from Elbasan.

The row was interrupted there, to continue further, across the door. on the opposite side, about twenty other old men were lined up. Across from us, at the distance of an outstretched arm, on the first floor were lined up: Hafëz Sabri Koçi opposite Father Zef; Mufti Faik Hoxha, Haxhi Xhevdet Alla, and in line after him, Professor Hodo Sokoli; across from me, the patriot Bajram Hoxha; agronomist Mihal Cerja and a group of isolated minorities. On the second floor, above us: the first one above Father Zef, Baba Bajram Mahmutaj – in line, Dervish Meleq Hasa, Rustem Gojka, Qani Mulita, Hebib Munishtirri, Bektashis who were also my semi-patriots, from Skrapar. On the second floor opposite, near the wall: Father Stavri Pilafi, above Sabri’s bed, after him Hirakli Sirmo, then they had made a place for Father Vaska, reorganized along with me, and in line, a group of Çams, with Lutfi Sejko and Maksut Xhumaka.

These were the ones with who I would now share my breath in the sleeping area and the free time that remained, until reorganization. Nevertheless, I would feel pampered by fate again; they had separated me from two beloved old men, I had gained two others, who welcomed me with the same love! On one side, I had a priest again, only now a Catholic, and on the other, an Uncle Esheref, only from the South. Across and above, in both rows, the most distinguished group of clerics there. I thanked God, and also my elders, for this wonderful combination.

As soon as I finished observing, after fixing as much as I could those who would now be my close neighbors, I tried to start a conversation with the old man on the right: ‘Uncle, where are you from?’ ‘From Kolonjë!’ ‘Why did they sentence you?’ ‘Because the Lady wished it!’ I was silent, I couldn’t believe my ears. The short answers of this eccentric old man did not open the way for me to push further. “Enough, this old man is a lunatic! Maybe he is confused from the crowd! Why waste my breath on him! Just sit still, without getting scolded!” and I buried my head between my hands and retreated into my shell.

The old man, a plump figure, dressed in thick woolen shajak, now when the temperature was quite warm, adjusted the black qylaf made of felt on his whitened head, coughed as if to clear his throat and turned towards me, with a mother-of-pearl box in his hand: ‘Boy, roll me a cigarette!’ He extended the box to me. I didn’t want to offend him, moreover ‘thank goodness he spoke’, so I took it, leafed through a sheet from the notebook, filled it with tobacco, and rolled it without exchanging a word, then handed it back to him with my hand on my heart. He took out his pipe from the pocket of his vest, filled it, packed the tobacco with his thumb, then pulled out a leather strap from the other pocket, at the end of which hung a lighter made from an anti-aircraft shell casing. He struck it, a burst of flame and black smoke, almost singeing his white mustache and eyebrows, then he lit mine too. With his head bowed, he puffed on the pipe.

I don’t know if he was thinking or if it seemed to me that he was deep in thought. He coughed a couple of times, as if choked by the bitter smoke of the tobacco that was sparking and emitting sparks from the bowl of the pipe. He took off the black qylaf again and scratched the crown of his head. At the moment I was completely distracted, I heard him ask me: ‘Hey, aren’t you Sulo’s son from Berat?’ He spoke and his eyes were fixed on the bed where he was sitting. I quickly gathered myself and turned to the old man: ‘Yes! I am from Berat, but I am not Sulo’s! Sulo and my father are friends.’

‘No, no! I didn’t say you were exactly Sulo’s, but the one Sulo kept close?’ He paused for a moment, and then continued: ‘Hey boy, a while ago you seemed to ask me, without exchanging tobacco? Don’t do that with others!’ He puffed on the pipe and exhaled the smoke. ‘Because you know how it is? Men sit down, exchange tobacco, and then start talking. If it suits you, you continue, if it doesn’t stick, you mind your own business, and the other minds his. Did we understand each other?’ ‘I apologize, when I asked you I didn’t mean to offend you!’ I apologized.

‘No, no! I wasn’t talking about myself, I am an old man and my grandson is older than you, but you must have manners!’ He puffed on the pipe again; some plumes of smoke came out of his nostrils, like gusts of a cold wind, forming a kind of saint’s halo around his white head. ‘Listen, boy, if they see that you are a useless stalk, they will put a mark on you here!’ He paused and exhaled plumes of smoke, thoughtfully took off the qylaf again and scratched the crown of his head: ‘Now tell me a little, who are you, where do you come from, and what kind of people do you have?’

I briefly told him who I was, where I came from, and my family. He listened to me and deeply puffed on the thick pipe he had packed with a handful of tobacco. When he finished, he knocked it on the board under the bed, took off the qylaf again and scratched his head; it seemed to be a habit. ‘Now listen to me! I am Dhimitraq Marko! Miço they call me, a Vlach from Kolonjë. Along with my brothers, I was the wealthiest of the kind, I had five flocks. Do you know that a flock has nearly three hundred head?’

I nodded my head, with a sign that indicated neither affirmation nor denial. ‘That’s how it is, I had about fifteen hundred head of sheep, as you say. And yes, I also had fifty horses and mules, because the life of the Vlachs is difficult without them. We wander all year from sheepfold to sheepfold, and we need wood for the dairy, we need to transport the milk churns from the pen to the dairy, we need to transport the wool, we need to move the people, the women, the children, and the elderly of the family, you understand that without horses and mules we are nothing! Where I settled, twenty tents were set up, my boy! And not just any tents, but king’s tents, come on! By God, if I’m lying to you! Even Zog has stayed in my tents! I was ‘Steel’ (‘Çelik’), my boy! I wasn’t some ditch vagrant, but a friend of Salih Butka and all the captains, up to the kaymakam, and yes, even all the great men of the church, up to the Epitrop of Kastoria! Did you get it?!

Now that we are talking, we have been settled in those parts since time immemorial. Empires and monarchies, sultans and kings have passed through there, and with all of them, we have been like wheat. They are kings in their affairs, we are kings in ours! May they live long, may we live long! Give and take and take and give, we have pushed through the generations, each one master of his own flock! We grazed our livestock, they governed theirs! And I have wandered through five states, mountain by mountain and pasture by pasture, and no one showed us the borders. Listen, by Saint Mary, I didn’t give an account to anyone!

I have been leading my people and my flocks of livestock for seventy years. And I have seen all those governments change. And yes, I have seen nizams and gendarmes, soldiers with gaiters of the French and the Greek, the German and the Italian, and no one messed with our affairs. If they needed something, meat, cheese, butter, curd, dairy, wool, leather; they rang the money, they bought them with golden Napoleons. Yes, by that holy church! But then the world was ruined for you, my boy! Because some mustard seed grew among us, who came with rifles on their shoulders and daggers in their hands, took our livestock and filled our pockets with pieces of paper, which they called receipts; ‘after the war we will repay you double!’ that’s what they promised us.

‘But what do I have to do with the war, please, I have a multitude of people to feed!’ I replied. But they wouldn’t listen, and yes, they got angry and reached for the rifle; but if it came to a rifle, I also had plenty, but where would I take the women and children! So, I accepted the pieces of paper. Come on, I thought, if I am well, who knows, maybe they will come to power! God grant, they pay me back after the war! But, I prayed with all my heart: may you never raise your head, and may I never see your faces! You see, the infidels won!” Memorie.al