By Lumnie Thaçi-Halili

Part Three

Literary research on the book “Memories of the Time with Kadare,” by Sulejman Mato; URA, Prishtina, 2025 –

Truth as the Axis of Literary Narrative

Memorie.al / Memoir literature is one of the most delicate spaces where memory and art intertwine. It gains a special dimension when the author chooses to write not about himself, nor about the work of a colleague, but about the man hidden behind the writer’s public figure. In this territory, sincerity becomes a literary act as important as language or style: to portray a friend with all his light and shadow is to affirm that the truth, however complicated, serves memory better than weaving praise.

Continued from the previous issue

The portrait of Kadare is that of a great writer with the complexities of human nuance, while the portrait of Mato is that of a writer who chooses to remember with wisdom, love, and integrity, transforming the memory into a form of uncontestable self-testimony about his own literary and human journey.

From this perspective, “Memories of the Time with Kadare” can be read as a self-portrait of Sulejman Mato in the mirror of his great friend: a writer who, by illuminating the life and work of the other, silently rewrites his own history, giving the memories the deepest dimension-that of human and literary communion. Throughout the reading of this book, we also learn about Kadare’s relationships with his fellow writers, which appear as a mosaic of complicated relations, where respect, competition, gratitude, misunderstandings, and, occasionally, some cutting irony-typical of his character-intertwine.

Mato reveals that, from his early years, Kadare had a circle of authors with whom he shared the ideal of literature, but also the challenges of survival under dictatorship: Dritëro Agolli, Moikom Zeqo, Sadik Bejko, Fatos Haliti, Çerçiz Loloçi later, and others.

With these figures, the relationship is presented as warm, based on intellectual respect and a shared joy for the artistic word. On the other hand, the book does not hide the tensions, recalling that Kadare was sensitive to servility and careerism in literature, and did not tolerate “imposing friends” who sought favors or read his work as a springboard for personal interests.

In specific cases, he also used the weapon of art to stigmatize a colleague in poetry or novels, even transforming them into coded characters that carry traits of those who had disappointed him, as happens with some allusions to B. Xhaferi, A. Pipa, or the bureaucratic figures who held power over literature at the time.

In short, in the book “Memories of the Time with Kadare,” his relationship with other writers is not presented along a single line: sometimes it is fruitful collaboration (as with Dritëro in confronting the censorship of The Palace of Dreams), sometimes it is quiet cooling (as with N. Jorgaqi, after late polemics), and sometimes it is a silent alliance against the regime (with N. Tozaj or new friends, in the Power’s “Bloc” who spread information).

This narrative reveals a Kadare who never sought to be the “all-liked” writer among his peers. He maintained an aristocratic distance, keeping close only those who brought creative energy, serious conversations, or intelligent humour. For him, literature was above casual companionship, and relationships were maintained only if they nurtured the idea of free speech and dedication to art. Therefore, the portrait Mato builds of Kadare in relation to colleagues is that of a writer who is cautious in friendship, selective, and often critical, but never cruel. He remains a man of contrasts: a friend who rejoices at the success of others, but also an author who staunchly defends his own creative activity. This relationship makes his figure more real, distancing him from any false myth of a “giant without a shadow” and placing him on the true stage where creators confront each other amidst passion, ambition, and the demand for authenticity.

In the final episodes of this collection of memories, Kadare appears weary of life, but not spiritually distant from Mato. He accepts his presence calmly, laughs again at his humour, accepts the donated manuscript of this book left on the table, and listens attentively even when he no longer has his former energy. As the narrative approaches its close, a silent acceptance prevails, accompanying the last meetings, akin to an unspoken reconciliation between two friends, aware that their time together is drawing to a close.

The Equilibrium between Feeling and Creation

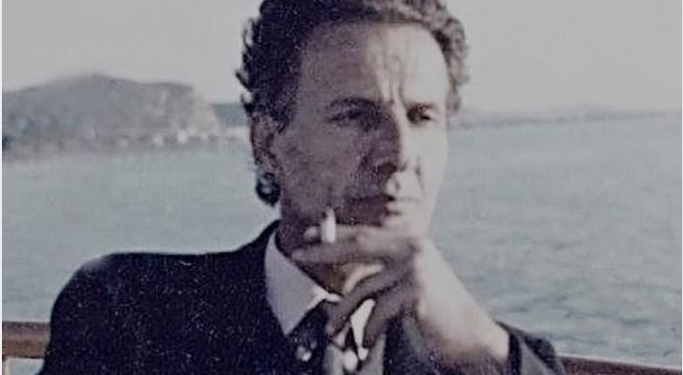

The book arouses curiosity about the young Kadare’s relationship with women, especially where his early years in Berat, Tirana, and Moscow are mentioned. A young Kadare emerges, oscillating between curiosity, shyness, and the desire to know the feminine world.

Sulejman Mato never makes this topic the axis of the narrative, but releases it as a current, scattering it across several scenes. Kadare comes across as a clever and ambitious young man who maintains a born elegance in his relations with women. In Berat and Tirana, he appears sometimes as an attentive companion, sometimes as a silent observer, who seeks more to understand than to conquer.

In Moscow, Mato recalls his tendency to contemplate Russian girls, but also his attraction to “beautiful Muscovite poetesses,” an attraction he himself accompanied with skepticism towards their sentimental poems. Nevertheless, the book reflects that for the young Kadare, women are a dual territory: an aesthetic inspiration and a test of character.

He is not seen as a man seized by the conquest of passions for them, but as someone who maintains a kind of intellectual distance; even when his humour touches the area of flirting, there is more playfulness and a writer’s gaze than unbridled temptation.

In this regard, Mato underscores that this relationship was never wrapped in dramatic secrecy; on the contrary, it was natural, clear, and often accompanied by a kind of sweet irony. For Kadare, (according to him) companionship with beautiful and intelligent women was a way to avoid the monotony of masculine conversations, to find creative energy, and to nourish his imagination. His early poems about love, which Mato brings back with quotations, show that after every glance or short conversation, he knew how to transform the feeling into polished verse.

Following this logic, in these memories, Kadare’s oscillations towards women are neither feverish adventures nor blind idealizations, but moments of search and experience, situated between personal ethics and the need of art to nourish emotion. The portrait emerging from the book is that of a young writer who tries things in life without breaking his inner measure, who knows how to maintain the balance between human curiosity and the creator’s discipline.

The Role of Intertext and Cultural References

Through this role, one sees how the narrative builds a dialogue with Kadare’s works (novels, poems, essays) and with the world tradition, bringing in Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Homer, Kazantzakis, Borges, Camilo José Cela, and even figures of modern culture, like Steve Jobs.

This dialogue, purposefully used by Sulejman Mato, creates a broad cultural map where Kadare is placed at the centre, raising his portrait upon a culmination of intertexts and literary myths. The narrator does not see his friend in a bare space, but places him in a continuous relationship with his own creativity and the culture that has nurtured him.

He dwells on many of Kadare’s books, such as The General of the Dead Army, Chronicle in Stone, The Palace of Dreams, The Doll, or The Palace of Dreams, as well as on poems like “The Deer,” “Longing,” and “Late Autumn.” These works are not mentioned merely for information, but to illuminate episodes of the writer’s life, showing how personal experiences were transformed into literary material.

Mato goes even further, showing that Kadare’s literary universe was not confined by Albanian geography. Through these references, Mato gives the reader a perspective on Kadare as a writer who built his identity on the bridge between classical tradition, modernity, and the Albanian experience.

This narrative weaving with the examples taken in the book creates a cultural landscape where Kadare appears as an author simultaneously connected to his roots (Gjirokastra, popular memory, Albanian legends) and to the galaxies of world literature. The mention of Hamlet, the Odyssey, Penelope, Homer, and even metaphors from Jobs, gives the book a universal breath and places the Mato-Kadare friendship against the grand backdrop of the dialogue between cultures and times.

Thus, in this sense, intertext is not an ornament but a critical and poetic tool, which makes Kadare readable as a figure formed by readings and myths, while Mato’s narrative itself becomes part of a larger tradition of “letters about the writer,” where biography, memory, and literature merge into one: “Memories of the Time with Kadare”!

Cities as Landscapes of Memories

The book in question gives a special role to cities and spaces, turning them into landscapes of memory and emotions, not just geographical coordinates. First, Gjirokastra, which is the fundamental ground; there Kadare’s childhood and the author’s roots are linked, the “mother spring” from which Kadare always draws creative material.

The narrow alleys are mentioned: “The Alley of the Mad,” “The Great Gate of Vasili’s House,” “Asim Zeneli” Gymnasium, the courtyards where children shared bread with jam. This city appears as a living myth, a laboratory of imagination where reality and legend coexist, becoming an incessant source for the novels Chronicle in Stone, The Doll, The Blunder.

Then comes Tirana, as a space for literary and social relations: the Writers’ League, offices, the bars “Juvenilja” or “Sky Tower.” Here Mato places intimate scenes (meetings, conversations, book donations) and official moments (plenums, critical meetings…). The capital becomes a symbol of public life, of the tensions between creativity and the political apparatus, but also a place of friendships and humour.

Unlike the previous spaces, Paris reflects freedom and clarity of vision; there Kadare regains creative power, appears as an author with international reputation, but without losing his longing for his roots. In this context, the poem “Easter Sunday in Paris” is mentioned, where through the verses he embraces Western identity without abandoning the Albanian core.

Berat carries a sentimental colour, linked to the period of youth, night conversations, and the first steps toward literature, memories that Mato and Kadare preserve as treasures of a distant and beautiful time.

While Saranda appears in softer tones, as a holiday spot and simultaneously a backdrop for the contrasts between privilege and simplicity, where the episode with Kadare’s car and the reflection on social divisions in the late ’90s are described: “It was a rare case for that time for a writer to have a driver and a car at his disposal. He had obtained this privilege not as a writer, but as the Vice President of the Democratic Front of Albania” (ibid., pp. 221-222).

These places are not just scenes of events, but nodal points where feelings, memories, and history intertwine, turning the narrative into an emotional structure. One can deduce that each of the mentioned cities also reflects the characters’ states: Gjirokastra preserves the light and mystery of childhood, Tirana reflects the tension between creativity and political control, Paris provides breath and perspective, Berat and Saranda bring peace, humour, but also reflections on time and status. In this way, the environments in these memories acquire symbolic and poetic value, creating a “spiritual topography” where Kadare’s life, Mato’s memories, and the cultural history of Albania converge.

The Metaphor that Sublimates Memory

Throughout the book, metaphors appear as bridges that move the narrative from biographical chronicle to a lyrical discourse of memory. Sulejman Mato does not stop at listing events but gives them a symbolic construction, making the book readable as literature in its own right.

Among the most powerful figures is “The Deer,” the animal “with antlers reaching to the stars, pursued by dogs”; it is not just an allusion to one of Kadare’s poems, but becomes a metaphor for the writer seeking creative freedom under the pressure of fear and power. The deer’s flight implies the creator’s escape from the “dogs of control,” while the antlers that “plough the heights” suggest the effort to open new horizons in literature.

“The Doll” symbolizes Kadare’s mother, but also all the silent figures who preserve memory and keep the family steadfast in the face of a harsh world. For Mato, this metaphor is a call to see Kadare not only as an author but also as the son of a fragile world, supported by unseen silence and sacrifices.

Another powerful metaphor is “The Laboratory of Memory”: “We extract memories from the reservoir of the past, while fantasy is nourished by it. It may happen that this reservoir is separated from the ‘creative laboratory,’ that internal laboratory of imagination and fiction” (p. 249). This laboratory appears as the secret space where Mato and Kadare store experiences to later transform them into literature. It is not just memory, but a field of creation where memories, myths, readings, and pains are mixed-a process that the narrative presents as an intimate experiment, an alchemy between reality and fiction according to the above reference.

Equally meaningful is the “Odyssey of Creation,” mentioned in the chapter “The Last Meeting” (pp. 244–250). Kadare is seen as a traveller passing through the narrows of the “Scylla and Charybdis” of dictatorship, temptations, glory, and loneliness, to reach the “Ithaca” of literature. This journey is not only that of the great friend and creator but also of the writer who narrates it, making the parallels between life and art visible.

In addition to these, the book is filled with place metaphors: cities appear as emotional landscapes (Gjirokastra “well of memory,” Paris “narrator of the past,” Berat “scene of youth”), making memory an internal poetic atlas. In general, the metaphors make the narrative transcend the boundaries of a linear testimony. They synthesize emotion, reflection, and history, giving the memories the dimension of a literary creation in their own right, as noted above. Through them, Kadare does not remain a subject with simple and clear biographical nuances but is transformed into a symbolic figure of genius living between memory and legend, while Mato, as narrator, testifies that memory, when truly sincere, can turn into the art of remembrance.

The Elegy of Memories and the Eternity of the Word

The path through the memories naturally leads us to “The Last Meeting” (p. 244), with the quiet conclusion of the book “Memories of the Time with Kadare.” This final meeting is not just a friendly memory, but a testament to the nature of creation, testifying that art is born from memory and transcends it to illuminate the world with the word of truth: “We met at the ‘Juvenilja’ bar-restaurant. The first impression he left on me was that he seemed tired and somewhat indifferent. But his eyes lit up when he saw me. After shaking hands, I took my book Secrets out of my jacket pocket and gave it to him. He immediately opened it, began flipping through the first pages attentively, and thanked me sincerely” (p. 244), (clarifying for the readers of this study that this refers to this book of memories).

In an autumnal calm, according to Mato, Kadare appears tired, but his eyes light up as soon as he takes the book in hand; behind the silence hides an internal vitality that makes the portrait deeper. The oblivion that “plays with him” is transformed into a metaphor for the clash between time and art, while the dialogue with the students (who had come to meet him there) reveals creation as a secret game of imagination, more than just knowledge of life. Memories are kept in a silent repository, warmed by the fantasy that turns them into literary matter, from which characters more vivid than reality itself are born.

The comparison with the Odyssey marks the creative journey as a dangerous but noble adventure, where art becomes a mission to illuminate the place and time. Kadare remains a master of memory and fiction, transforming life into a space where literature gains eternity. The last chapter of the book takes on the colour of a quiet elegy, where Sulejman Mato’s personal memory of his Friend or Brother, as he calls him at the beginning: “I have always felt Ismail as an older brother” (p. 6), turns into a reflection on the end of life and the eternity of art.

An unfinished visit, a book left on the counter, and a closed door become a metaphor for the boundary between life and departure. Kadare appears fragile, but enveloped by memory and work, while “the black July 1st” marks the silent reconciliation with death and elevates his figure from private boundaries to the space of national memory.

The allusions to Hesse, Hamlet, and Homer place him in a universal pantheon, while the farewell, “you became Homer, Aeschylus, and Shakespeare yourself” (p. 254), concludes his literary myth-the writer who gave name and glory to Albania.

The epilogue stretches as a reflection on the fate of literature and the reader’s thirst, carefully weaving the detail with the finesse of an artistic sketch. The book concludes with a clear affirmation, like a pearl of thought for the reader: great art remains for eternity, even when life fades.

Sulejman Mato has transformed the days with Kadare into narrative material for the book “Memories of the Time with Kadare,” where mutual hospitality, conversations, debates, silences, distances, and smiles become part of a human panorama. Through this narrative, he gives observant readers a gate to enter the room where the absolute prince of literature separates from the myth and remains only a man, while Mato himself remains there, invisible but present, as a voice of wisdom that gives clarity to memory in the name of truth. / Memorie.al