By Lumnie Thaçi-Halili

Part One

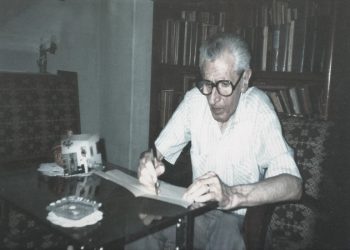

Literary Research on the Book “Memories of the Time with Kadare” by Sulejman Mato; ‘URA’, Prishtina, 2025

Memorie.al / The literature of memoirs is one of the most delicate spaces where memory and art intersect. It gains a special dimension when the author chooses to write not about himself, nor the work of a colleague, but about the person hidden behind the public figure of the writer. In this territory, sincerity becomes a literary act as important as language or style: to portray a friend with all his lights and shadows is to affirm that the truth, however complicated, serves memory better than weaving praise.

Veracity as the Core of Literary Narrative

Such examples are found in world literature, such as Ernest Hemingway (Hemingway, E. (2009). A Moveable Feast: The Restored Edition. New York, NY: Scribner), who gives us a Paris of the ’20s, featuring figures like F. Scott Fitzgerald, not just as a master of prose, but also as a fragile human, with his vices, fears, and human beauty. Then there is Constantine P. Curran (Curran, C. P. (1968). James Joyce Remembered. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press), who returns to Joyce’s early years in Dublin, presenting him not as a monument of modernism, but as a vibrant friend, with humor and ordinary habits. Meanwhile, Truman Capote (Capote, T. (1987). Answered Prayers: The Unfinished Novel. New York, NY: Random House) takes sincerity to the limit of gossip, transforming the narrative about his friends into a provocation on the relationship between memory and ethics.

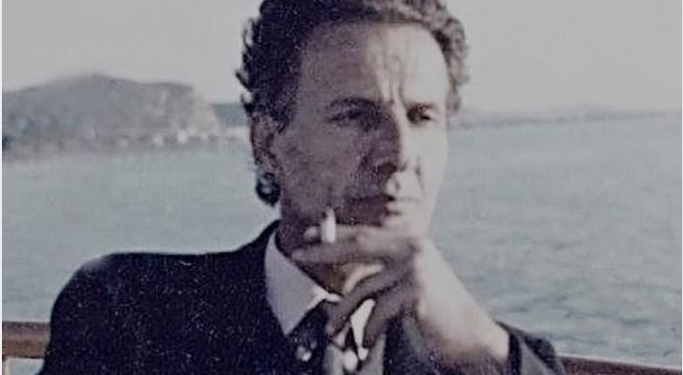

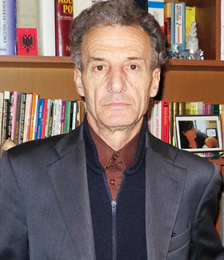

In this tradition, and with contextual variations, Sulejman Mato’s book “Memories of the Time with Kadare” naturally fits in. Mato views the most famous Albanian writer not as a fixed icon, but as a close friend, contemporary, and witness to more than just one era. Mato preserves in his memory’s conversations, situations, and fragments of daily life, giving the reader a Kadare painted with the vivid colors of humanity, without at all denying his creative greatness. Like Hemingway, Curran, or Capote, Mato chooses the honest path, carving the portrait of his friend with the pen of truth, showing that the greatest respect for a writer is to preserve his originality as he truly is.

The aforementioned works, from Hemingway’s Paris to Curran’s Dublin, from Capote’s salons to Mato’s memories of Kadare, prove that friendship and literature create a space where the past becomes a living narrative, and the portrait of a friend remains unforgettable only when it is true. It is worth mentioning, however, that Albanian literature already has such works, for example, a major work written about several literary figures or personalities by Ibrahim Kadriu, (Buzëqeshje miqsh-reflekse biografish [Smiles of Friends-Reflexes of Biographies], Faik Konica, Prishtina, 2025).

Unlike all of these, Mato’s book is structured differently; it sits somewhere between personal memoir, historical chronicle, and literary criticism—a genre globally known as the biographical-critical memoir (biographical notes with an analytical approach), closer to “conversations” and “portraits” than to factual, dry biographies.

The Intimacy of Friendship and the Public Testimony

Aside from carrying a very unique Albanian spirit, the book interweaves friendly intimacy with the context of the dictatorship, bringing forth not only Kadare as a writer but also the lives of the people of his time. Above all, it is, in essence, a narrative with many motivational layers, naturally combining personal and public reasons.

On a more intimate level, it feels like a testament of longing and gratitude, where the author seeks to keep alive the memory of a friendship that spanned from his youth until just before the writer Kadare’s passing (2024). Many fragments in the book possess a tenderness that surpasses a critical tone; these are narratives where one feels nostalgia for shared times, travels, conversations, books gifted to each other—for the warmth and shades of a relationship with a man who remains extraordinary, yet simple in his daily life.

This longing transforms into a way of keeping Kadare alive, not just through his work, but as a human figure. However, the book isn’t limited to privacy. It also conveys a public aim, an effort to offer the reader another Kadare—the one behind the novels, poems, and verses: the man who confronted the dictatorship, who maintained his space for creative freedom, who engaged in friendships, with arguments, with humor, with worries…!

The author best expresses this goal in the afterword, emphasizing his desire to build a portrait “with life details” to make the understanding of Kadare’s work more complete. Thus, the book assumes the nature of a historical and literary testimony, a mosaic that speaks to generations about how a great writer navigates between the pressures of the time and the treasure of fantasy.

In some fragments, there is also a spirit of homage; the author recognizes his friend’s rightful place in national culture and European civilized memory. But this homage is not rigid; it is accompanied by light humor, sincere memories, and episodes where Kadare appears as an ordinary man, sometimes with weaknesses and hesitations, saving the book from the exaggeration of grandiosity (bathos).

Furthermore, the motive is not singular but a network of reasons: longing and nostalgia for the friend, the need to preserve the memory of an era, the desire to provide a testimony about life under the dictatorship, and the will to gift the public a more complete portrait of Kadare, beyond the aura of the canonical author. This is illuminated by I. Kadriu’s note: “For some time now they have remained hostages in memory, hostages full of the charm of a human closeness, when that closeness happened with the author’s will” (Ibrahim Kadriu, Buzëqeshje miqsh, “Faik Konica”, Prishtina, 2025, p. 531).

The De-Mythologizing Aspect of the Portrait

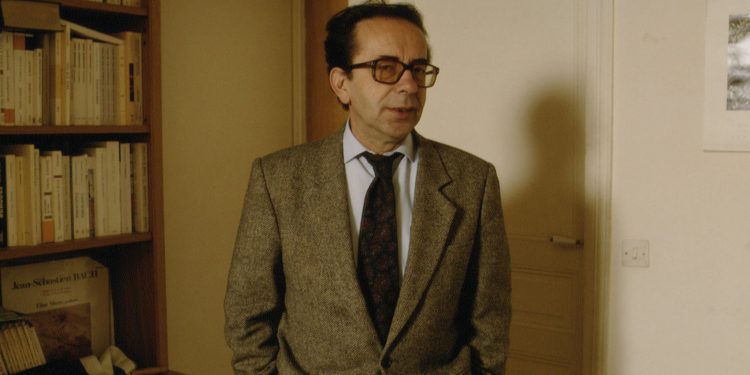

On the other hand, this book can also be seen as a form of gentle criticism and a “stripping away” of excessive idealizations of the Kadare figure. Sulejman Mato does not just write to exalt him; he seeks to place his friend in a more natural light, where greatness coexists with human fragility. Through episodes where Kadare appears tired, reserved, sometimes cold or deep in thought, Mato offers a genuine portrait, far from the unreachable icon (always referring to the book under review).

In many fragments, he brings back memories where the writer’s humor, whims, nervousness, or disdain are not hidden. These are in no way denigrations, but a way to make his figure more complete, to liberate him from the rigidity of the legend. In this sense, the book has a de-mythologizing dimension, showing that Kadare, besides being an everlasting giant of letters, was also a human with shades of light and darkness, with tiredness, with moments of forgetfulness or resentment, and with simple daily rituals.

The portrait of Kadare is constructed with a subtlety that avoids glorification, presenting the writer as an ordinary man. This is also evident in the dialogue between Mato and Kadare, when the former tells him: “I’ve made you a negative character,” I told him, certainly in jest…” (Sulejman Mato, Kujtime të kohës me Kadarenë, ‘URA’, Prishtina, 2025, p. 5).

Then comes his ironic sentence: “Negative am I,” he seemed to be in a good mood. “Oh, the hell with it! Why must a person absolutely be positive?! He can be negative too…” (p. 6). This easily demonstrates that it frees him from ceremonial grace and returns him to everyday simplicity. This critical aspect also appears in the analyses of his works, as Mato does not view Kadare’s creation as an untouchable temple, but as a universe where it is worthwhile to observe the mechanisms, distinguish the narrative tricks, and compare the successes and aesthetic value of each text in his books.

Even the language of the memoirs itself, with its mosaic of conversations, notes, and anecdotes, creates a sense of unraveling, inviting the reader to enter the writer’s “workshop,” to see the creative process and the relationships that influenced him. Therefore, this book is not just a homage or nostalgic testimony, but a literary portrait, where love and sincerity for the friend are accompanied by the courage to see him as he was—a complex personality, extraordinary in art, but affected by daily life, and faithful, as he himself attests in the book: “…starting these memoirs, I bear in mind the advice of the distinguished Russian writer Anton Chekhov: ‘My God,’ Chekhov wrote in his letters, ‘do not allow me to speak and judge about what I have no knowledge of!’ (ibid., p. 8).

Narrative Structure and Kadare’s Relationship with Power

The structure of the narrative in the work encompasses a wide arc, from childhood memories in Gjirokastër, with its cobbled streets, to his entry into Tirana’s literary life. Sulejman Mato does not offer a simple sequence of facts but constructs a mosaic where politics (like Stalin’s death and its echo in the stone city), art (Kadare’s early poetry), and daily life are connected in a calm and well-thought-out narrative cohesion. This approach allows the memoirs to transcend the boundaries of privacy and give the narrative a documentary function on the climate of the 1950s and 1960s.

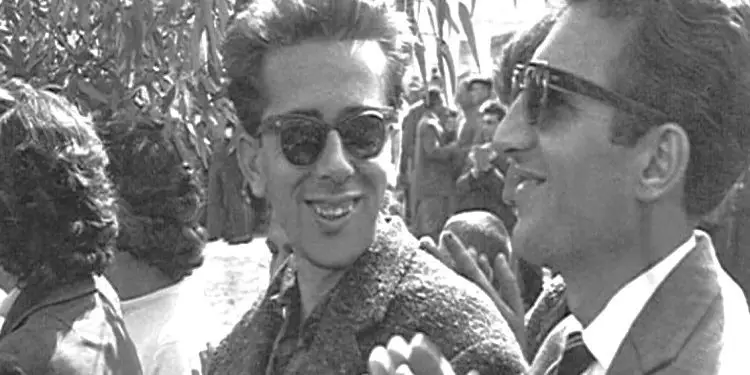

Against this backdrop, Kadare appears as a multifaceted figure. Initially, Mato portrays him as a bespectacled boy walking on the cobblestones of Gjirokastër, a simple yet elite image that conveys the promise of a future creator. Later, the portrait expands: the student returned from Moscow, uninhibited, with humor, trying on boxing gloves at Ahmet Golemi’s place; the poet who knows his own worth but maintains a quiet disdain for success; the one in love with Helena, involved in the atmosphere of student evenings, etc.

These and other vignettes shift him from aristocratic iconization to everyday simplicity, without denying his noble manner, and without diminishing his creative greatness; on the contrary, they make him more tangible, accessible, and human. It is worth mentioning that the chapter “Berat” constitutes the narrative heart of Sulejman Mato’s work.

Here, the figure of Ismail Kadare appears in its fullest dimension: arriving from fame and simultaneously immersed in the daily life of a small city; free, ironic, impatient, present in the ordinary scene of life. Mato constructs the portrait not from the distance of a balanced biography, but from the proximity of a friend and witness who sees the writer appearing “a man among men.” The topography of Berat becomes part of the narrative: the “Moska” restaurant, the promenade along the Osum River, the narrow room with the closed window.

There, Kadare appears as an ordinary man: playing cards, rejoicing when he wins, getting upset when he loses, making calls to the caretaker (dezhurni), seeking to fill the void of the day. These scenes make the writer unravelable and understandable, removing the mask of fame. However, S. Mato does not forget to include the tension between public visibility and Kadare’s desire to become “unnoticed.” The students who read him in school and see him on the promenade in the afternoons create a track between his work and his body, between the known figure and the man who seeks to remain a simple resident of that town. This duality makes the portrait richer and more sincere.

In addition to other details, Mato shows us a writer Kadare who knows many folk poems by heart, not as a collector of motives, but as a laboratory of figuration. However, his critical observation about verbal rhymes (“folk poetry has too many verbal rhymes… it makes the poetry like bejtes [couplets]”) (p. 43) reveals him as a reader with high prosodic standards, who does not accept ease at the expense of the discipline of form, despite the weight of Thimi Mitko’s work Bleta shqiptare (The Albanian Bee) on his bedside table. Meanwhile, in “A Scenario That Was Never Written,” Kadare is seen in the clearest light of humanity, as he summarizes reality in ironic twists, chooses silence over noise, feeds the day with rituals, and translates time into literature.

Through Mato’s eye, the writer’s portrait emerges as believable and vivid, testifying that genius does not sit on a pedestal but walks on cobblestones, smiles at meaninglessness, and remains always faithful to the correctness of the word. On the other hand, the relationship with power in the narrative shows a Kadare who instinctively rejects officials and empty ceremonies. His failure to return greetings, avoidance of invitations, skepticism towards meetings, and distance from “cadres” are part of a counter-protocol that preserves the creator’s freedom. His “perverse” humor, which mocks the futility of meetings, is a defense strategy but also a clear sign that the writer refuses to waste time on unsubstantial rituals.

Creative Arrogance vs. Humility

In the book, Kadare’s arrogance is treated as a point of interpretation—a pride he openly declares and transforms into an ethical self-acceptance, positioning it against the arrogance of others: “I have been arrogant. I admit it… and I haven’t been harmed by this” (ibid., p. 66). In this context, “arrogance” does not imply hubris, but quiet pride and creative self-confidence, a strong conviction in the necessity of achieving the highest personal standard. It is a shield that protects him from futile ceremonies and “cloned bureaucrats.” The author of this book clearly explains that this is not arrogance, but a kind of shield that allows the author to preserve time, mind, and the freedom of creation, by not dealing with trivialities.

From another perspective, Mato portrays Kadare as an author who is clear about the weight of the word. He works with discipline: three pages in the morning, a little in the evening. This strict regimen places him far from the myth of spontaneous inspiration, turning creation into a measured process where talent coexists with method.

I want to pause at the chapter “Three Letters” (pp. 89-102), which proves that memoir prose can contain the tension of a thriller while preserving the weight of historical truth. Through careful details and unforgettable scenes, like the arched gate, the cake with candles, and the red cloth of the tribune, the narrative turns a personal story into a reflection on the fragility of intimacy and human dignity in the face of ideological violence. The following chapter, “Life Scraps,” brings specific vignettes that converge into a subtle reflection on the cultural and social daily life of the 1960s.

Only here, the narrative takes on a soft color of nostalgia when the author of this book visits Kadare’s new apartment for the first time, where his encounter with the television creates a warm domestic atmosphere. The technical detail (the black-and-white screen, the antenna near the window) acquires a symbolic charge. The television is presented as a window to another world for him, a “prophecy of Jules Verne,” giving the reader the taste of an era when every technological novelty seemed like magic. Memorie.al