By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part thirty-nine

Memorie.al / I were born on 12. 23. 1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the ruthless investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, brutalized me at the Branch of Internal Affairs in Shkodër, they split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, after breaking several ribs, half of my molar teeth, and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the pitiful Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After half of the sentence was cut, because I was still a minor, sixteen years old, on November 23, 1968, they sent me to the political camp of Reps, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaçi camp, where on May 23, 1973, during the revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were condemned to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a process more than normal in the democracy we aspire to. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Renaissance” government sent Order No. 2203, dated 10.23.2013, for the release from duty of a police officer. Thus, Divine Providence was interwoven with the Neo-communist “Renaissance” Providence and, precisely on the 23rd; I was replaced by, no less and no more, but the former Security operative of the Burrel Prison. What could be more significant than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

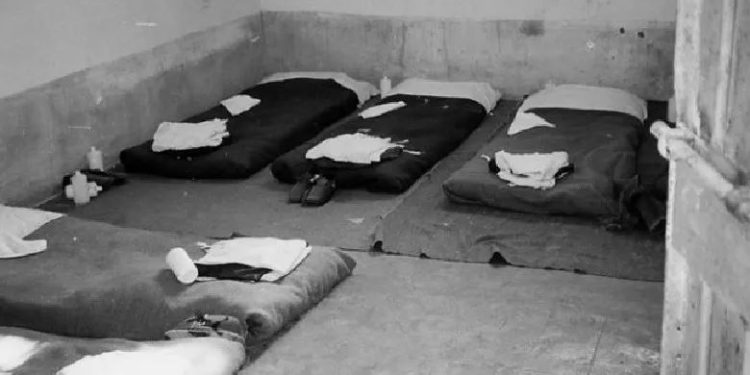

R E P S I

(Forced Labor Camp)

Memoirs

The Confrontation with the Foreman

Up at the top of the yard, the “Korroziu” (Foreman/Corrosive) stepped into a wooden shack, while I waited outside for instructions. After two minutes, he gestured for me to approach from the doorway. I went there. – “Did you want a coffee with a hand on your heart, sir that you’re waiting so aloof? What are you waiting for, to be invited with ceremony!?” – He scolded me with irony. – “No one asked you for coffee! – I shot back full of malice. – Even if you gave it to me, I’d never accept it from your rotten face!” – I glared at him. He probably didn’t expect this reaction, as I noticed he shrunk back, and then forced a grin: – “I didn’t mean it that way; I just wanted to make it clear that we are here for work!” – He softened. I understood, he was scared. From now on, I wanted to exploit the advantage the isolation cell had given me. Through my friends, I learned the prevailing opinion in the camp, that for anyone sentenced for a beating like mine, it was said:

“You have to be careful with them, because those rascals don’t care about giving you a shovel to the head too, and then try to find justice!” “For a start, my lessons à la Muharrem Dyli is turning out to be beneficial, both seen and done! Usually, these types need it this way, because if you put them down, try to keep them down afterwards!” I felt that my stubbornness had been effective. – “Come inside!” – The foreman, still grimacing, invited me in in a low voice. – “Listen carefully now: in my brigade, only three tools are used: the pick-o-phone, the wheelbarrow-o-phone, and the shovel-o-phone (qyrekofoni), there are no others. Since you are Vaska’s friend, who is also my friend, I’ll give you the chance to choose. You have the wheelbarrow, the pick, or the shovel. But I advise you to take the shovel (qyrekun), as you’re more famous for that one!” – He handed me a handle, accompanying it with another meaningful grin. – “It’s not that the work is easy here, but the wheelbarrow with that clumsy wooden wheel is very heavy, it shreds your ears all day with its screeching. But the pick is even heavier, because the ground is rock, and try to pierce it with a pickaxe; the shovel is a little easier, because, after all, if there’s no dug material, you have nothing to load. Do you understand me?” – And he grinned again like a sycophant. – “I think so!” – I grabbed the handle he extended and went outside. I didn’t know exactly where I was supposed to report, as the groups were made up of three people. They had been working together for a long time, and I, as a newcomer, didn’t have a defined group yet, so I waited for the foreman.

Joining the “Rebel Brigade”

A few meters away, about ten or twelve people were walking and chatting. In some wooden wheelbarrows, they had thrown the work tools, which were noticeable only by the handles over the side, but what they were exactly, I couldn’t distinguish. The foreman headed straight for them, and I followed. When I approached, I greeted them with a dry “good morning” and leaned on the shovel handle, staying somewhat isolated. The “Korroziu” said something to them, but I didn’t hear what, then I saw one person break away from the group and come toward me. He was a stout man, about fifty years old, with twisted but not very long mustaches, his body slightly hunched from the weight of suffering or motives, he greeted me: – “How are you, lad! Where are we from?” I told him who I was and where I was from. He laughed and joked:

– “May you enjoy the shovel, but how becoming it is for you! Just look, my friends, how much trust the Party has in this one; they gave him the tool right away!” – And he continued to laugh loudly. This idiot annoyed me; I was about to retort when one of the group further away intervened: – “Leave him, Xhelal Bey! Come closer!” – He addressed me. – “Don’t listen to Xhelal Bey’s talk, that’s just how he is!” – He seemed to apologize for the gestures of the previous speaker. – “Wait, do you know this one, Xhavit? No, you don’t know him, shut up and don’t talk! This is the shovel boy!” – The mustached man explained, waving his hands in the air. – “Which one did you say?” – “The one who made that s.o.b. eat his own s.h.! And then did a month in the cell for the shovel!” – The rat-mustached man continued his babbling.

– “Oh-ho-oh-h, so it’s you! – Xhavit turned to me, surprised. – Well, come closer, you’re one of us!” The whole group turned their gaze toward me. – “This boy, he’s truly one of ours!” – a fat man with a Gjirokastra accent chimed in. I felt welcomed; they seemed to accept me because everyone was smiling and shook my hand warmly. Brigadier “Korroziu” assigned me to work in a group with Xhavit Murrizi, a farmer from the villages of Kavaja, and Tafil Tafani, a cheeky jester with mustaches; also a farmer from the villages of Dumre. So, even though I knew nothing about the work, I now had my own group.

We started with introductions. They asked me and I asked them where they were from, why they were sentenced, and the usual small talk, then we started working. Each with his own tool. Tafil was digging, I was loading with the shovel, and Xhavit was pushing the wheelbarrows to the slope, about a hundred meters away. We continued like this until noon. When the whistle blew for a break, we took out the bread wrapped in cement sack paper, ate that dry bite, and lit a cigarette. Meanwhile, they introduced me to the neighboring groups. Since they were the first ones to welcome me, I’ll mention them all in order:

-The man from Gjirokastra was Professor Agim Musta, who would also become my history teacher and a friend of mine, even today, after forty-two years. He had been sentenced with the group of Pjetër Arbnori, for the illegal creation of the Social-Democratic Party.

-Professor Vangjel Kule, my fellow citizen, a former geography teacher at the “Babë Dudë Karabunara” Pedagogical School, sentenced in the early sixties with the group of the doctor Thoma Dardeli. But unlike the rest of the group, who were punished for ordinary crimes, political charges were fabricated against Vangjel, and he ended up as an enemy of the Party. He would become my geography teacher, and also my close friend, until he died after the nineties.

-Assistant Professor, Richard Richy, an Albanian-American who came to Albania with his mother. In early 1945, she came to be near her mother in Korçë in her final throes. But after the old woman’s death, mother and son remained in Albania because they were no longer allowed to leave for America to their loved ones. Thus, the mother would end up under the ground, and the son in prison, where after about thirty years of suffering, in 1988, he too would end up in the prisoners’ cemetery in Shën Vas. He also became my foreign language teacher, and we maintained our friendship as long as we could.

-The teacher Marko Popoviç, from Vraka of Shkodra. A thin man, always sick, who had been sentenced for agitation and would die before democracy. I also benefited a lot from him, especially in the exact sciences, mathematics, and physics.

-Kosta R…, a minority member from Mursia, a driver by profession, quite agile and very intelligent, a true artist, who had a painful end. After a violent isolation, he suffered a psychological trauma and later never regained his mental balance until he was found drowned in Bistrica in the eighties. I had very close relations with Kosta, even after he went “off the rails.”

-Hajri Pashaj, a young man from Hekal of Mallakastra, in his thirties, a brilliant musician; it was a special pleasure to watch him play the drums; every moment you would hear him either singing or lightly whistling pleasant tunes. He had a tragic but glorious end. In the Spaç revolt, on May 22, 1973, he would clash fiercely with his fellow villager, the former Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, Feçor Shehu, and would end up executed, today without a grave. As fellow provincials, we got along very well.

-Xhaferr Dema, a tyrannized man from Dibra, about sixty years old, a drinking enthusiast, so much so that he exchanged his wife’s ring for a bottle of plum raki. He was very humorous, and even in the most painful moments, he knew how to lift the morale and humor of others. Ignorant police officers often confused him with the former Albanian Minister of Internal Affairs during the German invasion years, Xhaferr Deva, and for this, he had suffered several times. Until the issue was clarified, Xhafa waited tied to the pillar on the “Golgotha” road. I was very close friends with Xhafa, who jokingly used to tell me: “Son, when you happen to be in Tirana, take a couple of steps to Xhafa’s café, andlet’s have two or three shots!”

-Mujë Balaj, a cheerful man in his mid-thirties, from one of the best families of Mbishkodra, very dear and correct with everyone. I also formed a close friendship with Muja.

-Xhavit Murrizi, from the villages between Kavaja and Lushja, was a tireless worker, a sincere man, a father figure as they say, loving and compatible. I also had a long friendship with Xhavit.

-Tafil Tafani, was a worthy scion of the distinguished Tafani tribe, known throughout the Dumre area, and even further in the Elbasan district. Heroes had emerged from this tribe, so much so that in every important national event, a Tafan would certainly be present. Tafil was in prison along with his cousin, Rakip, an elderly man with old customs. Both were a model of men of honor (besa). They had supported the fight against the invaders, lined up with the partisans, but when the agrarian reform began, and then collectivization, they would quickly become disillusioned. During the late forties and early fifties, the efforts of the nationalists intensified, the Tafanis became shelter and lodging for them, but the games of the British and Russian counter-intelligence, with Kim Philby, caused many of these nationalists, friends and hosts of the Tafanis, to fall into the trap of the State Security. This was their end, and finally, the sword of the infamous class war fell mercilessly on the distinguished tribe. The men of this tribe found themselves in political prisons. Thus, Tafil, as a worthy bearer of this surname, upheld the name and dignity of his ancestors. He was proud that he was the man with the biggest mustaches in the prisons, for which he took special care. I quickly became friends with Tafil, thanks to mutual acquaintances and friendships.

I deliberately left Xhelal Bey for last. Xhelal Cenko, was a simple peasant from Starja of Kolonja. He belonged to a family of nationalists who had served the great Bey families of the area for several generations. He boasted that one of his great-grandfathers had been a retainer of Zylyftar Poda and that Zylyftari himself had given him the title Bey, which the great-grandson tried to inherit with honor, through unbelievable and unmentioned sacrifices. When I met Xhelal, I noticed that he was somewhat deficient, but very proud. His pride was rooted in his heritage and extended to self-sacrifice. Xhelal was in prison for the second time. The first time he was sentenced immediately after the war with “one hundred and one” (years), as a member of Safet Butka’s gang; but after pardon after pardon, he was released after a dozen years.

He returned to his village and got married. A year later, a son was born, but this good omen was spoiled by the bad news of the creation of the cooperative. They collectivized all his belongings and small farm, which hadn’t been much of a fortune even when it was private. The title “Bey” was not real, but a vestige remaining from the time of the Tanzimat, when these titles had suffered inflation. So, a pseudo-Bey, fallen from grace, whose meager wealth: two fields, ten goats, two oxen, were taken from him, and in the end, he was left with his donkey, his wife, his son, and the honorary title. Xhelal’s economy took a nosedive. With his donkey, he barely earned a living, with a load of wood he sold in the city. He tried to scrape by with medicinal herbs that he collected in the mountains and streams of the village, but nevertheless, he struggled to protect the title with honor.

When he saw the clumsy villagers strutting around in tribunes and gatherings, he kept himself apart from the others: “I remain a Bey, so I cannot be equal to them. As much as a small corner can become a hearth, so much can a boor become a leader!” he judged, and continued in his way. He countered the pressure of the communists and the village youth with the stubbornness of his lineage. For this reason, a kind of silent struggle began between him and the communist brutality, which, with the terror of fear, wanted to bring even the ashes of the family hearth under control. Xhelal, as a man of his time, refused to send his wife to work in the fields, as the organization into brigades was called. He also refused to be part of the communist propaganda campaigns, and even with the stubbornness of a mule, openly loathed these methods.

But his obstinacy cultivated in him the vice of not bowing down; he considered himself a gentleman, even though he was currently dragging behind a donkey’s tail. When they called him: “Xhelal,” he didn’t even deign to turn his head. He pretended not to hear and continued his way; when they called him: “Xhelal Bey,” he stopped immediately, and if he was on the donkey’s saddle, he dismounted, greeted the interlocutor with profound respect, with the words: “lepe” (yes, sir); when they asked him a favor, he replied with special esteem: “peqe” (okay), even if a ten-year-old child stood before him. But this man, so gentle, educated, and polite, to the highest degree, as soon as someone mocked him with the epithet: “Comrade Xhelal,” he became furious and burst out like a vessel under pressure. He lost his temper, turned to the rude provocateur, with a low and vulgar vocabulary of a street ruffian such as:

“Xhelal of your mother and your father! O trash! O sluts and sons of whores, left in Serbian and Greek sheepfolds!” and others like these. His grandiosity to be seen as a gentleman had become an obsession, turning him into an object of humor and ridicule on the village roads and in the offices of the agricultural cooperative. This characteristic-vice reached the ears of the masters of the Internal Affairs Branch, who began weaving the net to then fabricate an hostile group, which supposedly agitated for the ruin of the cooperative and sowed hatred against the achievements of the people’s power. They provoked a meeting in the center of the village, inviting all the men of the area to the school yard. But first, they instructed some young people to incite Xhelal, and then they opened the meeting with the theme: “The fight against the feudal-patriarchal remnants of the past.”

During the debate, the young people pointed the finger at Xhelal as the bearer of the old and backward customs, then the presidium asked him for an explanation for his attitude, with a vocabulary fit for porters: – “Comrade Xhelal, how will you respond to these accusations?” – The bureau secretary, an ordinary weakling, without conscience or faith, intervened. Initially, Xhelal tried to avoid the debate, but when the provocateurs repeated it several times, he couldn’t stand it anymore, he erupted with curses and insults specifically for them: “Xhelal of your mother and your father,… etc.”! Right at this point, the meeting took the direction that the operative had planned; after they let him vent thoroughly, they put the handcuffs on him in the middle of the assembly, and after a month, with an exemplary trial, they gave him a ten-year sentence!

At that time, his wife was expecting their second child, and after three months in prison, Xhelal became a father of two sons. When I arrived at Reps, he had less than two years to finish his second sentence. I wouldn’t have spun out this story so long if the third sentence, for the same motive, hadn’t happened. As soon as he was released from prison, the youth, inspired by the Security, continued the provocations in the old style, and after eleven months, they arrested him again for agitation and propaganda. After adding another son to his family, they also added another ten-year sentence. So, he left three sons at home, who grew up as orphans with their father in prison; consequently, they were also enemies, born of an enemy. After the third decade, they would also tax him with a fourth ten-year sentence. Ultimately, the peasant from Starja, the inflationist Bey, completed forty years in prison.

And the one I left without including in the group remains the foreman, the “Corrosive,” Nasho. This man was an Aromanian (Vlach), sentenced with the Teme Sejko group, who, besides the Chams, whose trials he had attended as a witness without exception, had also condemned many of his own blood brothers, Vlachs. Nasho Gërrxho was the most discredited figure of the Aromanian community, he was the personification of evil but also extremely cowardly. Since a blood brother of his, similar in vice, had suffered badly, he felt terrified. This gave me the opportunity to pressure him, pretending I could use violence against him too, something that never even crossed my mind. But better the fear of the eye than the reputation; I had the chance to act like a “hothead” and I exploited it. Everyone was surprised by Nasho’s soft, almost servile behavior toward me, but the truth was hidden behind the shadow of a shovel (qyrek).

This was the part of the brigade where I was assigned to work, because the entire brigade numbered about seventy people, all of whom I would later get to know and who would know me. Unintentionally, thanks to a shovel, I became part of the “rebel brigade,” as it was called there, or the most homogeneous brigade of Reps, regarding the moral and political side. It had very few spies and many intellectuals from various fields, but also ordinary people, individuals with integrity and character proven throughout the endless years of prison.

The Etymology of the “Qyrek” (Shovel)

Now, a few words about the “qyrek” (shovel). The first time I heard this term was from an old man from Përmet, when the handle of the shovel I was working with broke. It was my first few days in the camp; at that time, I was with the electricians in the “technical workers’ brigade.” Uncle Takja was clearing the path next to the canal they had staked out for me to dig. Everyone knew him as a meticulous old man who treated his work tool like a mother treats her baby. That is: when he finished work, he cleaned it of dirt and other residues and oiled it with burnt grease. In the tool depot, Uncle Take’s shovel had a spot reserved just for it. At the same time, because he never refused anyone and always had a ready answer for everything, they considered him a fussy old man, with quirks and whims, and therefore they nicknamed him: “Take the Ready-Answer” (Take hazër-xhevapi). This was also because of the archaic words he used, inappropriately.

So, the day he lent me the shovel, he was working very close to the canal I was digging. The shovel they had given me turned out to have a cracked handle, where they had driven a nail to hold it. As soon as I plunged it into the earth, the handle remained in my hand, and the metal part with a piece of wood fell into the ditch. I begged Uncle Take to lend me his shovel, but before he extended it to me, he warned me: “Keep your eyes open, boy, don’t break my ‘qyrek’! Because you boys work messily, with all the strength you have! You break even iron, let alone wood!” Nevertheless, he gave it to me. I cleaned the remaining earth carefully; when I gave it back, I thanked him: – “Thank you, Uncle Take, good old age, and May you are healthy and well when you get out!” – “Hejvallah (May Allah grant your health), my son, may God give you long life, since you didn’t break my ‘qyrek’!” – He replied.

The term “qyrek” repeated a second time intrigued me, so without any tact, I asked him: – “What does ‘qyrek’ mean?” He gave me a look of disbelief, as if to say: “Who are you trying to fool?!” But he seemed convinced that I meant no offense, so he answered seriously: – “Man, don’t you really know that a shovel is called a ‘qyrek’?” – “No, I replied, I’m hearing it for the first time!” – “Hmm… alright, alright!” – he thought for a moment, then added: – “’Qy-rek’, ‘lop-atë’ (shovel), ‘lop-ë’ (cow)… aa, a cow, man! By God, it’s impossible! Man, do you see any similarity between a shovel and a cow, where this name should derive from?” – He asked me. – “I’ve never thought about it! But what similarity do you see?” – I asked suddenly.

“No, there is no similarity! And how can there be, man! The cow gives us milk; this one sucked the mother’s milk out of our noses! The cow gives us meat; this one ate our meat little by little! The cow gives us leather for sandals, this one flayed our skin! Do you understand now why the shovel should not derive from the cow! By Allah, there is no similarity! But with ‘qyrek’, it’s different!” – “Why is it different for ‘qyrek’, and not for ‘lop-at-ë’?” – I purposely teased him. – “Man, ‘qyrek’ clearly comes from Turkish.” – “Explain the meaning, Uncle Take!” – I quipped again. – “The meaning, what does it mean? To tell you the truth, I don’t know exactly either, but surely, it has nothing to do with the cow!” – Uncle Takja concluded his etymological explanation.

Naturally, this very empirical explanation didn’t completely convince me, but since no other synonym came to mind at that moment to satisfy his taste, I accepted it. Later, I heard this term more often from others as well, so it no longer made an impression on me, and when the shovel happened to become my self-defense weapon, I accepted the designation “qyrek” without hesitation. That’s all, just for etymological culture, even without scientific facts. Memorie.al