By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part thirty-five

Memorie.al / I were born on 12. 23. 1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the ruthless investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, brutalized me at the Branch of Internal Affairs in Shkodër, they split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, after breaking several ribs, half of my molar teeth, and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the pitiful Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After half of the sentence was cut, because I was still a minor, sixteen years old, on November 23, 1968, they sent me to the political camp of Reps, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaçi camp, where on May 23, 1973, during the revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were condemned to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a process more than normal in the democracy we aspire to. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Renaissance” government sent Order No. 2203, dated 10.23.2013, for the release from duty of a police officer. Thus, Divine Providence was interwoven with the Neo-communist “Renaissance” Providence and, precisely on the 23rd; I was replaced by, no less and no more, but the former Security operative of the Burrel Prison. What could be more significant than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

R E P S I

(Forced Labor Camp)

Memoirs

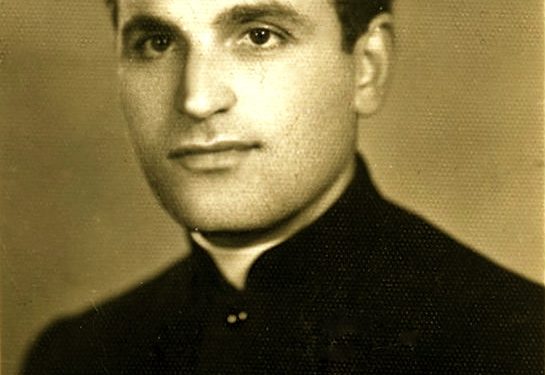

Dom Mark’s Farewell and the Philosophy of Resistance

Dom Mark continued: “In this HELL, worse than HELL, we must save what can be saved. However, it will take many sacrifices and years to overcome it; and in the end, not everyone will reach that day. Time has proven that often the Antichrist, or to say it more clearly, the anti-human, has fought and subdued the good for a certain period, but nonetheless, the good has ultimately triumphed. To spread Christianity, countless sacrifices and extraordinary will were needed; many martyrs fell on the long journey; in old Rome, they had to hide in caves and catacombs. Conscious Christians ended up on crosses, like their leader Christ, but they did not weaken; after much suffering and ordeal, the blessed light and the lamb of the Almighty God, Jesus Christ, triumphed. Even later, good and evil have been in an inexhaustible war, and in the end, good has triumphed, regardless of the price that had to be paid.”

“We are now at the same stage; communism is the Antichrist, the anti-human, aiming to physically eliminate all its opponents. The communists are merciless atheists, immoral, they are bloodthirsty and unbridled cynics; to achieve their wicked goals, and they use every means and have no intention of turning back. They have filled the prisons, not because the prisoners have committed crimes, but to spread terror among the masses. They have put us inside, not just to kill us-if they wanted to do that, no one would stop them, they would have gotten rid of us completely. But they fear the forbidden fruit; elimination would turn us into martyrs of faith and nation. Therefore, their goal is to discredit us in the eyes of the people, by publicly cursing and beating us, to lose our reputation, and then to die slowly, like forgotten dogs in the prison cells.”

“This wicked method of behavior has necessitated the counter-reaction. So, to seek ways to ensure continuity, and for this purpose, we must preserve the people, to be able to get them out of prison alive. But these people must be young and well-formed, honest and trustworthy, wise and learned, but above all strong and patient, to go far. And now I want to emphasize, this plague will not disappear quickly, it will take years until the end. And finally, I want to add, that my generation and many others will be left by the wayside; we have neither the physical ability nor the age to reach that happy day…!”

With such conversations, and sometimes in imposed silence, since the priest was communing with the ether, we reached the afternoon when the priest finished his sentence. On the day he left the cell, we parted as old friends. We had spent over two weeks together that were physically a twenty-four-hour torture, but spiritually, a flight to the eternal skies of divine freedom. What I learned those days, I hadn’t grasped in all the years of my life combined; those two weeks in my soul saw the most important catharsis, hatred was placated, and the foundations for the future spiritual edifice were cemented. The moment the police opened the cell door to take him out; the priest walked to the threshold, stopped there, and raised his head high, as if to take in the missing sky, then turned towards me and, with an outstretched hand, made the sign of the cross.

– “May Jesus keep you under His protection, my son! May you finish healthy and with a clear conscience!” – He threw his blankets over his shoulder and, folded in half, with a slow pace, he headed down towards the infirmary. I followed him with my eyes, up to the bend past Noja’s store, and then headed for the latrines. When they released me too, we met affectionately. As long as we were in the same camp, we saw each other often, although the priest was almost always ill.

But very soon we would be separated, yet, nevertheless, we would remain close friends. Despite the fact that later our paths would no longer intersect, and fate would not help us meet again alive in this world, the friendship and help of the humanist priest, Dom Mark Hasi, would never be lacking for me. We heard from each other through the prisoners who moved from one camp to another or from the camps to the funnel of the New Tirana Prison, where they gathered new convicts from all the Internal Branches of Albania, to then send them to different destinations, to exploit them as unpaid labor.

To receive and send news, we also used alternative routes, such as the prisoners sent to the prison hospital, for which the new prison’s “funnels” remained the sanctuary and distribution point during the ins and outs from the hospital. So, through those who moved on this itinerary, I maintained contact and exchanged information with Dom Mark. Meanwhile, from the friendship born during the weeks we spent in the dungeons of Reps, which later consolidated, I gained immeasurable benefits; I acquired knowledge and new friends, and in return, I gave only a thank you: “Thank you Dom Mark, for everything you did for me!”

But even this “gift,” the martyr priest did not want to accept and told me: “I did my duty. May God forgive me, if I did not complete it to the best of my ability?” Later, when I learned of his death in prison, I was deeply distraught. The departure from life of that man of the mountains, devoted to his sacred duty, who dedicated himself to Jesus until the last moment and sang with full veneration, with his special voice, whose echo still resounds in my ear, as it did forty-two years ago, deprived the Arbëror land of a great man, but added one more saint to eternity. Eternal glory, oh stoic priest!

The Instinct of the Fox, the Dog, and the Wolf

The night I was left alone, I felt like the loneliest person on the planet, like an orphan abandoned even by God Himself. I spent hours without sleep, recalling and re-recalling the past conversations with the priest. That’s how I pushed through, until I finished my sentence. Guests for one night or twenty-four hours were brought to my cell, except for one from Mat, who was sentenced to three days. I didn’t get to know these short-term visitors, nor did I attempt to engage in private conversations; even when a dangerous topic happened to arise, I remained silent. I recalled the advice of the wise priest:

“Be careful, my son!… the wicked people and the spies have increased here…! And the poor wretch doesn’t know where to guard himself first…,” so I only exchanged general conversations with them, without going into details. Not that I necessarily thought they must be bad, but simply because I didn’t know them. Each one immersed himself in his own troubles, and we pushed through the night, until dawn. The next day, he would go with his companions, while I remained right there. Without any notable event, I closed the term of the sentence, down to the last minute.

During that month, I acquired some new notions that, in other circumstances, I hadn’t even imagined. But these can only be entrusted to someone who has had the chance to know the camp cells. In that isolated environment, some previously untried habits were born and developed unconsciously. Without realizing it, a new habit, a new idea, a kind of imaginary perception, subtly interjected itself into the individual’s life, transforming the consciousness, like the trickle of water that erodes the rock day after day; it caused the acquisition of some conditioned reflexes, like those in animals, which they transmit genetically from mother to offspring.

After all, this is what communism aimed for: to turn the most intelligent being into an instinctive animal, to subdue it more easily, to defeat it without resistance, so that they could then eternalize their final dominion. They had turned us into guinea pigs! Thus, the dungeons had been turned, more or less, into laboratories where they conducted studies on survival. The abnormal conditions of this perverse “laboratory” dictated the acquisition of some paranormal traits that, in another environment, would make even the most cynical person laugh at himself. To illustrate, I will give an acoustic example: Just by hearing the clatter of studded heels, you had to be able to determine whether the person approaching the dungeons was an officer or a policeman; or simply from the echo of the boots’ stomp, you had to guess with whom you would have to face off, with some old shrew or some thick-headed arrogant one.

Specifically, when the operative came, he walked stealthily like a fox tracking the hen houses, waited a few minutes behind the door, with his nose plunged into the keyhole and his ears raised, seeming to have developed the senses of smell and hearing. After making sure he hadn’t been noticed, he suddenly opened the door, to catch the isolated prisoner off guard, with some forbidden item, and then start the pressures: who gave it to you, who brought it in, etc., etc.

When the camp commissioner came to inspect the dungeons, the stomp of the studs echoed from afar, as if to let us know that there; “where the Party treads, even the mountains roar!” Then you had to be able to distinguish, only through the manner of breathing or looking, the one who came to perform the service within the norms, from the one who aimed to cause artificial confusion, to then begin reprisals. Thus, the instinct to distinguish the well-intentioned from the ill-intended developed to perfection.

My friend from Vlora, Luan Koka, whenever these secondary qualities of the human character were discussed, would say: “Let us be thankful to the communists, who are doing us a special honor, by equipping us with the instinct of the fox, the dog, the wolf, the cat, the hyena, which particularly distinguish these intelligent animals from the others. With these qualities, which are their distinguishing features, we can confront them more easily! Hee-hee-hee! Poison against poison!” – my friend would conclude, and naturally, he was completely right, because depending on the assimilation of these senses, we were able to organize our daily defense and escape many, many ordeals, many, many traps that they set against us.

Thus, the cell sharpened the intelligence, sight, hearing, and sensation, in the most invisible aspect, those that zoologists have classified as “dormant instincts,” which they find impossible to stimulate in a cage, in a tamed animal. In a way, communism transformed the modern human into a guinea pig animal. I barely pushed through the last day of the sentence. The minutes and hours became months; I could barely wait for the moment they would take me out. I hadn’t washed for a whole month, so I was disgusted with myself. That afternoon, two policemen and an officer, whom I was seeing for the first time, disembarked at the cell. With my eyes fixed on the door hole, I followed their actions; they stood a few meters away and were talking about something. I pressed my ear against the hole, hoping to catch a fragment of the conversation, but in vain, they were far away and speaking softly.

I fixed my eye again and stared at the newcomer; he was a scarred man, about thirty or more years old, with a face full of deep pockmarks, as if punctured with a nail point, which gave his complexion an even heavier shade than it might actually have had. After finishing with the cell next door, they opened the door to my dungeon. – “Is this him?” – The scarred man asked. – “Yes, as you commanded, Comrade Commander!” – “Hey you, how many days have you been here?” – He turned to me. – “Thirty.” – “How much had they cut it?” – “One month.” He was devouring me with his eyes. – “But this month seems to have thirty-one days; you will complete it tomorrow!” – He added and made to leave.

It was as if I was hit by stones right in the middle of my forehead; I was so shaken at that moment; I had counted the days one by one. So as not to be mistaken, every morning I scraped a line on the plaster of the wall. “Hey devil, where does this come from now, I need one more day!” My mind almost left its place; I couldn’t stand it and turned to him: – “No, Mr. Commander, you have miscalculated, we are now in February. This month has twenty-eight days. Thus, I appear to have done two more days!”

– “Hey you, are you at the top of your head, or do you miss the irons!” – One of the policemen glared at me. – “Hold on, hold on, so you want to teach us what month we are in, huh!” – “We are in February…!” – “Shut up, man! Your face is going to tell us how many days the month has!” – And he puffed up like a rooster in front of my nose. But the officer, who had taken a few steps down, returned again. “Heck, why did I look for it like a goat at the butcher’s!” I thought when the scarred man was looking intently. “Wait until they beat me black and blue with clubs!” and I hid in the corner behind the door, to somehow protect myself.

But after taking two steps, he stopped at the top of the stairs, then turned to the police and ordered: – “Take him out and fill out the forms, but if he repeats it, next time him will do one day extra!” – And he took the slope down, without adding anything else. – “Hey you, what are you waiting for, or do you like the hotel!” – The one who had just glared at me mocked. I took my blankets and personal belongings from the shelf and followed them.

As soon as I went down the stairs, I turned towards the dormitories. – “Where are you going, hey you?!” – I heard the voice of the policeman from behind. – “To the barracks!” – I replied. – “No, you fool; this job doesn’t end so easily! You enter here easily, but you leave with difficulty!” – “I didn’t know!” – “Well, learn now!” – “I will try!” The ironic expression seemed not to please the policeman, because he threatened me: “Do you know that you have beaten someone, hey you?!”

– “I finished my sentence!” – I defended myself. – “You finished your sentence, but you have to sign the official report!” “Big trouble, to do thirty days in the dungeon, every single one, and here now, this cursed report appears, which needs to be signed?!” but I didn’t dwell on it and followed them. The police in front, I with the blankets and bag in my hand behind them, we entered the small office of the guard officer. Inside that miserable office, where they first put us on the first day we arrived at the camp, it was hot. In a carbide barrel adapted into a stove, the fire rumbled, having reddened the side walls of the tin. The foul smell of carbide, which polluted the air of that narrow space, almost suffocated me.

After thirty icy days in the cell, I couldn’t stand the hot blast; my head was spinning. I approached the door to stay as far away from the stove as possible. Meanwhile, the police took off their thick coats and sat on some crooked chairs, next to a table that immediately tilted, as if it were on three legs. On its surface lay a thick register with gnawed pages, as if rats had nibbled it. They took out another one from a shelf fixed to the wall and began to write.

I leaned over to read the official report that one of them was filling out; as soon as I rested the palm of my hand on a corner, the table almost slipped onto my feet; it seemed that it really had been on three legs. – “Open your eyes, hey you, or do you want to destroy the office too now!” – The policeman opposite me angrily blurted out. – “No, I wanted to read what is written in this paper!” – “Your mother’s paper!” – the other one next to me threatened and dropped the inkwell on the dirty surface, and was looking at me as if he wanted to devour me. – “It’s not paper, hey you, it’s an official report! It’s more than paper; it has the Party’s seal on it!” – And he grabbed the gnawed sheets and shook them in my face.

– “Listen, hey you!” – And like a predator, he snatched the collar of my fleece. – “Look, it’s stamped, look where the Party’s seal is too!” – He almost poked my eyes out with his untrimmed fingernails. I pulled back a little, looked at it carefully; a smudged ink blot, whose writing was incomprehensible, stood out on the sheet. Surely, the inscription “REEDUCATION DEPARTMENT NO. 303 REPS, SHPAL, MIRDITË” must have been engraved in bas-relief on it, because they used this address in official documents and we wrote it on the envelopes of the letters we received and sent, twice a month to our families.

“Eh, what unheard-of irony! They use “DEPARTMENT” when they should emphasize “PRISON”! As if we were a battalion of recruits in military training and not a colony of political prisoners! Classic mockery, in modern times! The person is supposedly re-educated through mistreatment, and moreover, in the second half of the atomic century! Oh God?!” I didn’t want to prolong these meditative sophisms, but I could barely wait to escape from their clutches and get outside. Behind the office window, I glimpsed the silhouettes of my dear elders, who were gathered in a cluster.

– “I saw it!” – I confirmed. Quickly, I glanced at the content, because I feared some trick. So, after reading common things, like the date of entry, the date of exit, and the reason for the punishment, I didn’t prolong it further, but quickly initialed under my name and towards the door, and out. As soon as I reached the threshold, the elders rushed towards me, one snatched the blankets, another bag, and others me myself. They hugged me affectionately, as if meeting children they hadn’t seen for a long time. At that moment, Dom Mark’s words echoed in my ear, when he told me: “Neither you nor I are parents, to feel a parent’s pain…,” and I agreed with him. I had to touch and experience that murky February afternoon myself, to grasp the essence of those golden words. Post prova! (Or the carriage, the carpet, the bagel.)

Immediately, outside the guard officer’s door, I found myself overwhelmed in the arms of the cluster of elders who were waiting there. Sulua, Vaska, Uncle Sherefi, Uncle Dauti, Meleq Hasa, surrounded me, each one trying to touch me with their hand, perhaps they couldn’t believe their eyes that I was among them. Rizai and two other elders greeted me a little further away, while a group of over ten people smiled at me from the terrace above. Most of them were strangers, or simply those I had only seen by face. In a line uphill, two by two and three by three, we took the stairs to the barracks.

The procession was led by Uncle Sherefi, who, with cheerful remarks, spread the message: – “Make way, men, the professor has returned! Now he has just passed the exam, and has graduated with the assistant’s diploma!” Without reaching the upper platform, he turned to me: – “Hey fool, is the kettle ready, first go wash yourself! Give me the ‘diploma,’ and leave the lice in the bathroom! We don’t want you to bring them as a present to the bed, you naked one!” – He snatched the bag from me and made a half-turn with his face towards the showers: – “Go on then!”

Without delaying, I turned towards the showers. There, my compatriot, Bajram Hoxha, was waiting for me with a bundle in his hand. We embraced affectionately, and then he led me into one of the partitions where he had spread a worn blanket. After hanging the clean clothes on a nail, he brought two fire-blackened buckets, and I entered the shower. Of course, it was not about baths in the true sense of the word; there were neither showers nor boilers for hot water installed there, but they were simply named that way, to distinguish them from the latrines, which they called bathrooms.

– “You have everything inside! Go in, wash, but hurry, you’ll get cold! If you need more hot water, just call!” – The good Bajram moved away outside the small room. I took off my dirty clothes and threw them out from under the blanket. I remembered the hayloft on the first day and the ordeal I went through, so I kept it short; after throwing a couple of scoops of water, I quickly lathered up, foamed myself with a wool rag, rinsed, wiped, dressed, and went out. I got rid of the cell scum!

I thanked Bajram from the bottom of my heart, that short man, a man of few words but much work, who did for others what he never did for himself, and then I headed for my sleeping place, where I hadn’t stretched out for a month. I climbed the wooden stairs and sat down among my companions. When I found myself there, a special feeling of satisfaction seized my soul. It felt like I had returned home, after a long and tiring exile! “It’s strange how a person changes! Even that seventy-centimeter territory, where they had forcibly caged us, one would consider it property, even when it didn’t belong to the individual, but to the camp command! And even the two neighbors, unknown until yesterday, one would see as family members!”

I was pondering these thoughts at that moment, but I didn’t have time to delve deeper, because acquaintances and strangers were approaching, shaking my hand, giving me a “get well soon” or “it’s over,” depending on the dialect, and leaving, to make way for others. I, who didn’t expect this entire crowd, extended my hand mechanically, saw off the first one with a “thank you” and waited for the next one. I couldn’t believe that in such a short time, I had become so well-known!

But I had been wrong; the endless line of elderly or sick visitors, whose names I didn’t even know, forced me to change my mind. Locked in the cell, I thought that in a month, even those I had worked with would forget me, let alone others! But events had flowed differently. In the camp, my gesture had been given the strangest colors. It had been brought up and conveyed, judged and over-judged, spun long in conversation after conversation, and in the end, the effect this news had produced had taken a meaning completely opposite to what the command aimed for; that is, to intimidate the other young people through terror.

Because the healthy part took this gesture as a positive example, they served it to the newcomers as the best way to act, when they found themselves in the same conditions or under the pressure of the spies and immoral people introduced by the operative. But there were also those who considered this action an extreme, excessive, almost crazy reaction. Nevertheless, in interpretations, the positive opinion prevailed. Memorie.al