By Prof. Dr. Bardhyl Çipi

Part Two

SCIENTIFIC PROOF OF IMPRESSIVE DEATHS

(Public figures, victims of dictatorship, and other events)

Memorie.al / Bardhyl Çipi are one of the most experienced specialists in Albania in the field of Forensic Medicine and Bioethics, their teaching, and the training of new forensic experts. Some of his cases include: victims killed at the border while trying to escape the communist dictatorship, whose hidden bodies were found with the help of a loyal dog; an interned woman who committed suicide out of despair; citizens of Kosovo killed by Serbs because they wanted to live free and not be humiliated and tortured; residents who lived in Albania 1500 years ago; a professor from the University of Tirana who was robbed and murdered; and others. This book is about death and the scientific evidence for discovering different types of death: murder, suicide, those induced and forced by the communist regime, murders and genocide against Albanians by their neighbors, and fresh, decomposed, and skeletal remains. It also documents the deaths of prominent figures like Kennedy, Lincoln, Napoleon, Lenin, Trotsky, as well as the deaths of ordinary people. The book provides knowledge on the changes that occur after death and the examination of human remains around the world and in our country, from a historical, ethical, forensic, and legal perspective. Some of his recent books are: “Manual of Forensic Medicine” (2015), “Bioethics in Albania nowadays” (2016), “The Albanian Transition through the Lens of Forensic Medicine” (2018), and “Forensic Criminalistics” (2020).

Continues from the previous issue

Medical Secrecy in General and After the Death of a Patient and Public Figures

The preservation of secrecy is a very important issue for the respect of human freedoms and rights, which is also provided for in the Constitution. According to the Constitution, non-interference in a person’s private life is guaranteed unless authorized by law (Article 35) (Elezi, 2002).

The Albanian Criminal Code includes several articles that criminalize the dissemination of personal secrets (Article 122), unjust interference in private life (Article 121), and obstruction or violation of correspondence secrecy (Article 123), etc. (Criminal Code of the Republic of Albania, 1995).

This principle is also very important in medicine and is provided for in the Albanian Code of Medical Ethics and Deontology. This is even truer today, as the risk of its violation has become greater due to the development of electronic media, computers, faxes, voice messages, etc.

Under these conditions, a new medical legislation has started to be drafted in many countries for these issues.

However, the field of medical secrecy after death is not as well-known as it should be. It is important that its various aspects are also known in our country, because recently there have been many publications here, accompanied by discussions and criticisms, especially in relation to the illnesses and deaths of some public figures.

General Knowledge on Medical Secrecy

Is it permissible to publish everything about the medical studies carried out on the human body? Can all medical data on illnesses and the cause of death be made public by doctors? Should efforts be made to discover post-mortem data on the human body, such as the consequences of criminal acts or suspicions of their commission?

Is it possible that the application of the principles of medical ethics-confidentiality, consent, and respect for the human body after death-are conditioned by the period of time that has passed? (Charlier, 2014).

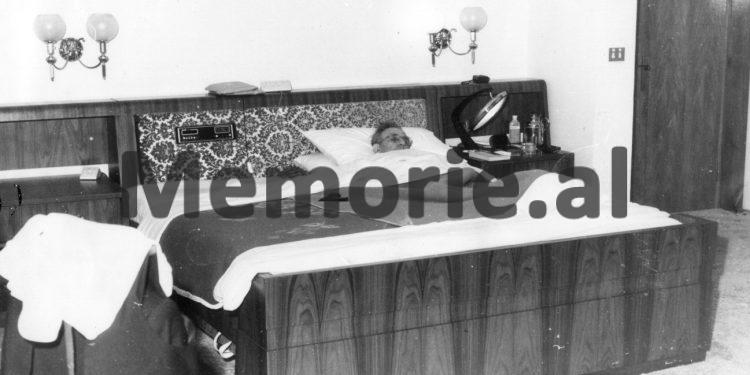

Recently, these questions have also started to be raised in our country, especially in relation to the medical data and deaths of public figures from the previous regime, such as Enver Hoxha, Mehmet Shehu, Nako Spiru, etc., or those who were persecuted and killed during that period.

To understand them, we must first analyze the important principle of medical confidentiality, which from a moral obligation was transformed into a legal obligation and finally into one of the fundamental human rights (B. Çipi, 2015).

According to this principle, in protection of the patient’s interests, the information that the doctor receives from them during the exercise of their medical practice should not be told to other people or spread. In the absence of a guarantee that their secret will be preserved by the doctor, the patient may keep important data hidden that could negatively affect their treatment, or that of other people (B. Çipi, 2005).

In fact, the concept of medical secrecy in many countries, especially Western ones, has a close connection with that of the privilege of the doctor-patient relationship, a concept that is narrower than the confidentiality of patient rights. According to it, the treating doctor should not reveal the data they receive from the patient to a third party and should not use it against the patient in court or other legal proceedings (Robitcher, 1968; De Witt, 1959).

Recently, the issues of medical secrecy are being given more and more attention, in relation to their ethical and legal aspects. The great development of electronic media and the achievements in the fields of medical genetics have changed the meaning of the traditional transmission of medical information.

The use of cell phones and today’s electronic devices – computers, faxes, etc.- have made it possible for unintentional violations of medical secrecy to occur. Voice messages sent electronically can be heard by people other than patients.

Likewise, the computerization of medical data, which has many advantages, risks violating their confidentiality (Berg, 2001).

For this reason, a new medical legislation has been drafted in many countries to protect confidentiality in different circumstances (Guidance and advice, confidentiality and disclosing information after death, 2021).

Medical Secrecy after Death

Medical secrecy after the patient’s death and for public figures constitutes a special, not very well-studied field.

In this study, some of the main aspects of this issue have been analyzed from foreign literature that deal with the concept of preserving or not preserving medical secrecy after death, the philosophical and ethical arguments of these positions, the circumstances in which this secret is not kept, the influence of the time that has passed since death, who will have the right to keep or not keep the medical secret after death, etc.

The preservation of medical confidentiality after death is necessary to protect the individual, either for their private life or their social position, due to the primarily moral damage that could be caused to the patient, in case this medical data were to be revealed (Berg, 2001).

Today’s concerns about confidentiality relate mainly to the issue of when a doctor reveals a venereal (sexually transmitted) disease, or that the person was an alcoholic, or other data that may be offensive to the public, or if the disclosure is made to protect against a defamatory act by the patient.

Likewise, blood groups themselves may not be information that should be kept secret, but in cases of paternity determination issues along with DNA, they can be very important.

For example, in the cases of the identification of the corpses from the Srebrenica massacre, carried out by the Serbs in Bosnia, through the comparative examination of DNA data with those of their living parents, it turned out that in some cases the father of a victim was not the real biological father. This finding was necessary to be kept secret to avoid subsequent serious family conflicts.

Or in the case of people affected by HIV/AIDS, this disease must be kept secret even after their death (Berg, 2001).

Failure to maintain medical confidentiality after death can occur because doctors have not made any promise to their patient to keep medical data after their death.

In fact, even though this is foreseen in the ethical codes, few doctors have shown the obligation to preserve the confidentiality of specific patients, and even less so for medical secrecy after death.

According to foreign medical literature, the protection of medical confidentiality after death depends on the interests the deceased had before death, in order to preserve it.

So, if the non-preservation of post-mortem medical confidentiality will be in favor of the deceased person, this cannot be objected to (Berg, 2001). Philosophical views regarding the interests of the person after death (Berg, 2001).

The interest of the deceased person is to have their information preserved, if its announcement after death would harm them, for example, by not keeping the promise to preserve medical secrecy that could affect the memory of the person when they were alive, or from defamation that could cause them moral harm.

In truth, the deceased person, whose consciousness has disappeared, has no reason to have interests. But, when they were alive, they had interests that should continue to be preserved even after their death.

The relatives of the deceased also have interests, which are determined by the fact that the deceased lives in their memory. Thus, damaging the memory of the deceased by not keeping the medical secret by doctors will damage the interests of living people to keep the virtues of the deceased person in their minds.

It may happen that for a person who was very correct during their life, the disclosure of confidential medical data changes the opinion of all their acquaintances so that they now understand that they were a person with flaws, a phony.

From a philosophical and ethical point of view, there are two positions regarding the preservation of confidentiality after death (Berg, 2001):

-The first position, according to which, the preservation of confidentiality after death should be much stronger, to have an absolute character, in comparison with medical secrecy before death. This is because the person who has died no longer has the possibility to approve this non-preservation of confidentiality, or to defend their reputation or identity.

-The second position, according to which, the interest of the deceased person to preserve their confidentiality will be smaller than when this person was alive. This is for the reason that the person who has died cannot be harmed, in the sense that they no longer feel pain, happiness, or other emotions.

While for a living person, the non-preservation of confidentiality, for example medical confidentiality, will harm them and make them suffer from this action, due to the consequences of this disregard for their wishes.

Some other situations of non-preservation of medical confidentiality after death (Guidance and advice etc, 2021):

-cases of denunciations for the medical follow-up of the person before death,

-in cases of contesting wills,

-when medical documents of insurance companies are requested by relatives, which are necessary for financial benefits, which are determined by the medical cause of death of their person who was insured in these companies,

-the need for relatives to learn about the diagnoses of inherited diseases of the deceased person, in order for them to take medical measures to prevent them,

-the interest of studying the course and distribution of various diseases (non-preservation of confidentiality is only for the researcher and not for other people),

-the interest of publication, e.g., for events with multiple deaths from specific diseases, or when the deceased person is a public figure,

-cases of medical information requested by the media, bibliographers for general interests, for the discovery of criminal events, etc.

The Influence of the Time That Has Passed Since Death on the Preservation or Not of Medical Secrecy (Berg, 2001; Charlier, 2014)

Over time, the memory of the deceased, which is kept in the mind of a living person, begins to fade.

Likewise, the interest of the family members of the deceased, over the years, will decrease.

In this case, it should not be forgotten that the memory of the people who knew the deceased is much more important than what has remained in the subsequent generations.

Therefore, the protection of medical confidentiality after death will decrease with the passage of time, until its complete disappearance.

In foreign literature, there is a point of view, according to which, confidentiality should no longer be preserved when a period of time has passed that corresponds to one or two generations after the person’s death.

In French legislation, this time has been 150 years; later it was reduced to 120 years, and there is a tendency for this time to be reduced even more.

But it is emphasized that even with the passage of the necessary time, this does not mean that the information should be made public (Charlier, 2014).

This difficulty to preserve or not to preserve this secret can also occur because the doctors in this case may have died over time, or because the medical documents of this case have been destroyed.

In practice, we encounter cases of our study of the medical or forensic aspects of corpses or skeletal remains from the past. They have not been “patients”, in the true sense of the word.

In medical legislation in general, the preservation of medical secrecy, both while alive and after death, usually belongs to the treating doctor of the patient.

So, in these cases, these will be considered as “deceased persons”, without life, but they must also be respected (Charlier, 2014).

Therefore, in the publications of the examinations of these cases, at least their anonymity must be preserved (Charlier, 2014).

Who Has the Obligation to Preserve or Not Preserve Medical Secrecy after Death?

This obligation belongs first of all to the treating doctor of the patient who has died; but this can also be for the doctor who performed the autopsy of the deceased person, or other medical personnel (Berg, 2001).

The request for non-preservation of medical secrecy can be made by the relatives of the person who has died, or by the person themselves before they died.

The disclosure of a medical secret can also be carried out by the doctor in the circumstances mentioned before, such as in cases of medical information requested by the media, bibliographers for general interests, clarification of criminal events, etc.

Cases from Literature

In 1965, Churchill’s friend and personal doctor, Lord Moran (Charles McMoran Wilson) published his book, “The struggle for survival 1940 – 1965”, immediately after Churchill’s death, a biography of Churchill’s life, based on the diaries that Moran had kept throughout the period from 1940 until Churchill’s death in 1965 (Robitscher, 1968).

The book was based on Moran’s diaries during all this time and contained two types of arguments (Robitscher, 1968):

-events listed in chronological order about what Churchill had done and expressed in his meetings with Roosevelt and Stalin, his remarks about the war, his opponents in Parliament, etc. This is because Lord Moran, as Churchill’s personal doctor, had been present in all these confidential matters, not in the role of a doctor, but in that of a trusted friend.

-arguments about Churchill’s health condition, which, if they had been made public during his lifetime, he would not have hoped to continue his duty as prime minister for another two years.

The publication of this book was accompanied by harsh criticism in the British press of that time (Robitscher, 1968).

According to them: Dr. Moran should have kept silent about what he had seen.

In the well-known journal Lancet, on the occasion of the publication of this book, it was emphasized that: “The public’s trust in the medical profession derives mainly from the conviction that what happens between the patient and the doctor should not be spread” and that; “If confidentiality is preserved while alive, it must be respected twice as much for the deceased.”

“By writing publicly about the health of an identifiable person, Lord Moran has created a precedent, which should not be repeated.”

Meanwhile, at the well-known British Medical Association, at its annual meeting after this publication, its representative body, composed of 560 members, took the decision, with only three votes against, in which Lord Moran was not mentioned, which emphasized: “The death of a patient does not release the doctor from the obligation to preserve secrecy.”

Despite these opposing views on this book, many opinions and arguments in its favor were also given in the discussions and press of the time (Robitscher, 1968).

According to them, “Lord Moran’s testimonies are very valuable, because through them the missing aspects of Churchill’s life have been revealed, first of all, through the public disclosure of medical testimonies.”

“A figure like Churchill cannot have any privacy. He belongs to the whole world, alive or dead, and everything that has to do with him, especially his health problems, have a universal interest” (Robitscher, 1968).

“We live in a time when public figures, alive or dead, become the subjects of biographers, secretaries, assistants, or family members. When everyone is allowed to write about these cases, then why are doctors forbidden from doing so?” (Robitscher, 1968). Memorie.al