By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part thirty-one

Memorie.al / I were born on December 23, 1951, in the black month of a black time, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief interrogator, Llambi Gegeni, the ignorant investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Internal Affairs Branch in Shkodër. They split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, and after breaking several of my ribs, half of my molars, and the thumb of my left hand, they sent me to court on October 23, 1968. There, the wretched Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After they cut my sentence in half because I was still a minor, a sixteen-year-old, they sent me to the political camp of Reps on November 23, 1968. From there, on September 23, 1970, I was transferred to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, during the revolt of the political prisoners; four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we aspire to have. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Renaissance” Government issued order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for the “Dismissal from duty of a police employee.” So, Divine Providence intertwined with the neo-communist “Renaissance” Providence, and precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced, no more and no less, by a former State Security operative from Burrel Prison. What could be more telling than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by his former persecutor!

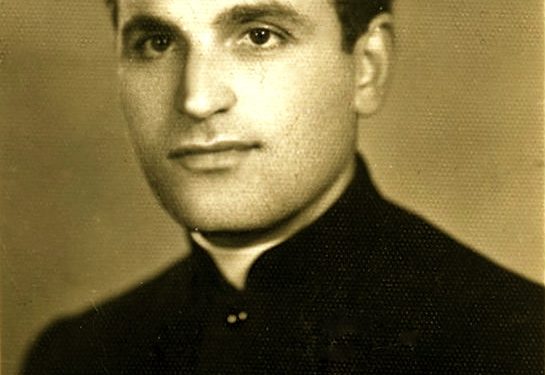

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

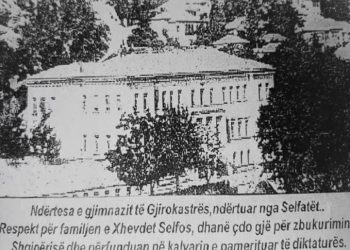

R E P S I

(The Forced Labor Camp)

Memoir

I rewound the “tape” to the moment when the assistant cook was looking at me strangely and the policeman intervened even more strangely. “Oh God, a long life to my friends! But who is this assistant cook whose name I don’t even know, really? And what does this policeman represent, who played dumb and probably risked his career, or even more?!” “Oh God! My dear parents! How could I have forgotten them?!” The idea immediately flashed in my mind that they, and only they, could have been the organizers of this unimaginable scenario. After all, who else did I have besides them? My throat tightened, and I couldn’t swallow the bread. “What kind of people are these?! To risk so much?!” This sudden change didn’t escape the Priest, whose eyes lit up with I don’t know what kind of invisible light.

“By the Great One, you truly have good friends!” this exclamation escaped him as if by accident. “Hey, but who are you?!” he added in surprise. “Dom Mark, I am a nobody!” “But your friends, man!?” “I don’t even know who could have made all this sacrifice! In any case, I owe them a lot! I’m in great distress until I can repay this honor!” “For now, let’s eat a bit, and then we’ll have time to talk about obligations! After all, today you need it more than anyone else, and your friends knew it!” He fell silent, took one of the halves of the bread, and broke it in the middle. A cigarette fell from the broken bread. “Look, look, they even put a cigarette in the bread!” In fact, it wasn’t a cigarette, but a piece of paper rolled into a tube so it could be hidden in as little space as possible. The priest took it, but he didn’t open it.

“Let’s eat first, and we’ll look at it later!” We started eating the black, greasy soup from the priest’s bowl. I had long since gobbled up mine. Now that my body had warmed up, the hunger returned, more terrible than before. I ate without fuss, even wiping the bottom of the bowl with my bites until the aluminum shined in the darkness; even soap wouldn’t have cleaned it better. Meanwhile, the priest ate very little and left the rest. “He’s tormenting himself, saving it for me!” I thought, but I couldn’t help but say: “Dom Mark, eat, we have plenty…!” “No, if I eat too much, I’ll die from an ulcer! ” he interrupted me. “I suffer from a stomach condition, my boy! We’re in isolation here, and I miss the baking soda with water, but even outside, the same thing happens!”

“I’m sorry!” I sympathized. “I have to take good care of myself, my dear boy! We’re in prison, and there’s no one to care for us…!” and he leaned against a corner. When I finished the last bite, I asked for the cigarette-letter. I carefully opened it, but the sheet of paper, a quarter of a notebook page, was not even as big as the palm of my hand. One side was filled with clean and clear, but very tiny, handwriting. It seemed that a master calligrapher had poured all his professional talent onto it, but in the dim light that penetrated the door, it remained indecipherable. After turning it over and over, I finally gave up. I handed it back to Dom, but he waited for me to read it first, so he folded it up.

“Tomorrow morning, a new day, a new fortune, as we say in Shkodër, we will find out who wrote it and what they wrote!” the priest concluded. Now full and warm, I felt better. My shoulder still hurt, but less, except for my wrists where the wires had been tightened. There were marks and some raised blisters on the skin from which a kind of cherry-colored liquid flowed. With my wrung-out but not-dried clothes, the priest blocked the space below the door, from which a cold draft of air was entering. Now that the icy current was no longer rushing in, the atmosphere inside the cell seemed to change. With the sleeves of his shirt, Dom made a bandage for both of my wrists. Now I was self-tied; I couldn’t stretch my arms more than the width of the cloth allowed, but at least the initial pain wasn’t bothering me anymore.

“You have to keep them like that all night! In the morning, you’ll feel light!” The wind carried to our ears the whistling of snakes. The whistles of the guards gave the signal for sleep. The priest got up and took the blankets. We had a total of four. He folded one in half and laid it flat on the floor, while he arranged the other three in a cross shape, two lengthwise and the third one crosswise. He formed a kind of box; it seemed that his long experience in prisons had given him expertise. “We have to lean back to back, in this small space!” I looked at him in surprise, straight in the eye, but I didn’t say anything. “We have to adapt to the conditions, my dear boy!” he explained when he noticed my doubtful look. “When one turns to a side, the other must turn as well. The corners of the blanket on top must be tucked under the body, so they don’t get lost!” the “Mentor” continued his explanation.

“What will we put under our heads?” “There’s no pillow here, my dear, all we have are our moccasins!” he replied dryly. “For tonight, we’ll use mine, one for me and one for you! Tomorrow, when yours are dry, we’ll have it sorted out!” “What about the cold, what will we do?” “If it’s too cold, one will sleep and the other will stand guard. And if it’s too cold, if you don’t want to freeze to death, we’ll both sleep squatting, either standing or with our heads leaning against the door!” “Oh, Great God!” it escaped me unintentionally. “Amen!” he accompanied my prayer with the sign of the cross over his thin chest and continued: “We have to do everything we can to sleep, because at five in the morning, they’ll take the blankets out and we’ll have to spend the whole day on our feet. Do you understand?” “Yes!”

“Well then, lie down, it’s getting late!” and he immediately took his corner. I also lay down. The instructions for the first night in the “hotel without rent,” as the old prisoners affectionately called the isolation cells, were useful to me this time, and they would be even more useful in the future. In the isolation cells in the camps, the conditions were much more miserable than in the interrogation cells. This was true horror. In winter, when the weather was cold, you couldn’t sit or lie down, especially during the day, because they took the blankets away early in the morning and gave them back late in the afternoon.

A prisoner punished with time in the camp cells, to escape paralysis or pulmonary tuberculosis, had to run, run, run endlessly. My friend Ismet Boletini, who liked numbers games, calculated: “A prisoner in a cell, every winter day, walks a distance of about forty linear kilometers inside the cell, or approximately the length of the Lezhë-Shkodër, Berat-Fier, or Tiranë-Milot roads. If you add to this the nighttime walks, it can come out to the length of the Tiranë-Durrës road and vice versa. If a person is punished for thirty days, they would travel an itinerary of about 1,200 kilometers, or a round trip from Tirana to Athens. Meanwhile, Tomor Allajbeu, who has been in the cell for four years, has walked about 20,736,000 kilometers, which means he has crossed the globe back and forth at the equator and the poles.”

“So, my dear friend, communism has produced explorers that even Armstrong would be jealous of, and they would have become more famous if they were allowed to discover the world!” he would conclude his “à la Ismet” calculations. A distinguishing feature of a prisoner who had turned the cell into his home was the rapid pacing with his head down, the sudden turns, and often talking to himself. When you came out of the cell, you needed a period of time to adjust to the environment and the people. This routine habit was compensated with walks in the prison yard. But even outside prison in free life, you could easily spot a former prisoner; all you had to do was carefully observe their instinctive actions, like walking quickly while hunched over, sudden stops and turns, sudden changes in tone, some even monologuing with themselves. All these prison habits often stuck with you for the rest of your life. This was especially noticeable in those who had spent a lot of time in isolation.

Since the cells had a very limited area, ranging from a minimum of five to a maximum of ten square meters, movement was also conditioned by these parameters. Within this perimeter, you could walk, but to avoid colliding with the wall or with your cellmates, you needed to make spectacular turns, because it often happened that there were more prisoners in a cell than its holding capacity. But even in the prison yard, where the number of prisoners was very large in relation to the space, you had to keep your eyes peeled to avoid collisions and encounters with undesirable people, who again were not few there. There were even cases when unwanted collisions took on unforeseen dimensions, with unforeseen consequences, even tragic ones.

As for the way of speaking, you would hear conversations with a thundering voice, but also muffled. For example, two people in a cell, to avoid the “pointed ears” behind the door, as the spies who eavesdropped on what the prisoners said about the regime were called, had to speak in a low voice, almost whispering. It sometimes happened that one of the conversationalists had hearing problems, and then the other would switch to sign language. In the bitter cold of Mirdita, it was impossible to survive punishment without getting pleurisy, which was the mildest form, or even severe colds, which caused incurable, and sometimes fatal, diseases. I have known many individuals who, after spending four months in isolation during the cold season, when they came out, were sent to a sanatorium to be treated for T.B.C., from which, even if they managed to return alive, they only had a temporary détente with the streptococcus, because they would return there again, only to come out in a coffin, broken in half and ending up forgotten in the desolate fields of Linza.

My friend with the same last name, Nuri Abazi from the villages of Skrapar, after months and months of isolation in harsh winter conditions, became a severe case of emaciation, spitting blood and ending up in such a state that he evoked pity. That healthy, agile boy like the roe deer of the mountains where he was born and raised turned into yellowish saffron, apathetic and anemic, so weak that you could see the water in his throat, and he had a very bitter and quick end. There are many other cases like this; anyone who has happened to have spent some time in prison knows them well. During the transition from spring to autumn, the cells were more tolerable and the temperatures were somewhat more bearable. With the exception of hunger, which was equivalent for all months of the year, as well as the physical tortures that did not change depending on the weather, the others were manageable.

But the horror of horrors remained the summer! In the hot months of the year, the cells turned into torture upon torture. The sun’s rays beat directly on the floor from morning until sunset, so much so that you would think the world was on fire. Inside the cells, the temperature reached record levels, added to this the lack of drinking water, which was rationed to only two seven hundred and fifty-gram flasks per day, one in the morning hours and the other in the afternoon. It’s easy to imagine the unbearable state the isolated person had to endure. The heat and hot air stimulated the greenhouse effect, aided by the floor and the cardboard on top of it, and even that little water became undrinkable. Often at the bottom of the aluminum flask, a reddish sludge would form, where thousands of tiny, red worms would swarm and swim without stopping. If you also consider the heavy stench that the two-meter hole of the bathroom behind the cell emitted, it’s easy to imagine what a plague you had to endure.

In that open pit, where the biological waste of human feces was decomposing, billions of worms with tails swarmed, often coming out of it and taking shelter under the blankets and clothes of the prisoner, even inside the bowl of soup. From the bursting of billions of bubbles that boiled and followed one another in this gigantic cauldron of biological waste, an odor similar to the burp of decomposing carcasses was released. And then to think that all this polluted air was inhaled and aspirated into human lungs, and about the endless amount of microbes and deadly bacteria it left as a souvenir there. The suffocating stench surpassed all types of torture, causing pathological and psychological disorders in the wretches who suffered it; so much so that they often paid the tribute with the most expensive price, their lives. Pathological, dermatological, and psychological diseases acquired in those environments became chronic and accompanied the poor person who got them for the rest of their life, until their carrier took them with them to the grave, but they could also transmit them to others during life’s tribulations.

Many political prisoners suffered in the Reps cells. My Skrapar friend Meleq Hasa, or Haxhi Meleqi, as he enjoyed being called, because in his early youth he had made a pilgrimage to Mecca, was one of them. That intelligent old man, an inexhaustible source of humor and folk ballads; uneducated in truth, but a born storyteller, nourished at the fertile spring of Kapinova, was very intelligent. I remember him with respect for his elegance in expression, especially for those special stories that left indelible marks on my consciousness and formation. Old Meleq was a cleanliness maniac; when he came to the faucet to drink or fill water, he would wash the bowl very well with soap or baking soda, until he was convinced that he had removed all the microbes, and then he would drink with his hands, never directly from the faucet. But he couldn’t stand the smell of soap produced in the Rrogozhina factory. Since there was nothing else, he used it out of necessity.

I often teased him jokingly: “Old Meleq, you’re suffering so much with this Rrogozhina soap, with pig fat, you’d better foam up some fig leaves!” “Ah, my boy, where can I find those fig leaves and that little green clay of my village, here in Mirdita! If only I could wash with them once, let me die in peace!” the old man pleaded and as he caught his breath, he added: “Even when I die, I will leave a last wish, that they don’t wash me with Rrogozhina soap, but with fig leaves and Kapinova clay! Only then will my soul find peace!” The cleanliness maniac was like those obsessive mothers-in-law who can’t stand their sons’ wives, and he, too, never felt completely clean. The elegant old man had established a strange relationship with water. When he happened to shake hands with someone, even at midnight with chattering teeth, he would get up and go to the faucet, wash his hands very well, and only after he was convinced that he was not carrying any microbes, would he lie down to sleep. Raised on the top of the mountains, where the dewdrop on a blade of grass resembles the pure tear of a child, he sought ecological perfection everywhere, an unattainable thing in prison conditions.

This virtue-habit had turned him into an allergic maniac towards any kind of filth. But one hot day in August, the cell door opened for old Meleq. They punished the poor old man with isolation in the cell. When he was put in, he was beautiful, handsome, and healthy as an apple, with full, radiant cheeks and a mustache trimmed short over his lips, where every hair stood in its place, like soldiers in a line, not a millimeter outside, not a millimeter inside. After fifteen days of isolation, he came out of the cell so changed that even his wife, if she had seen him, would not have recognized him. The good old Meleq had turned into a leper! The skin on his face and hands was peeled off; sludge similar to lymph was dripping from it; only his eyes and nails were recognizable. When you saw that old man disfigured by wounds, you were reminded of the forgotten stories about lepers of the middle Ages who were locked in quarantine so they wouldn’t spread the epidemic.

The smile had left his face; humor belonged to a bygone era! His open nature became gloomy. He closed himself inside a veil, with two holes torn for his eyes. Despite the titanic efforts of Doctor Naim Çitozi and the omnipresent Dilo’s medicines, that old man was still aesthetically and spiritually destroyed. On the day of his release from prison, when I saw him off, I wished him: “Old Meleq, thank goodness you made it to this day! I wish you good luck and a good old age, with your wife and children!” Do you know how that old man replied to me? “Ah, my son, I’m not happy about my release, but about the chance to find a cure from a doctor. If I could return to my former appearance for just one second, at that moment I would be happy to die!” But this wise old man was left with a memory from the Reps cells, eczema of the most aggravated degree, which gnawed at his body, soul, and even his heart. Although he left no doctor or hospital unturned, he found no cure. He spent the rest of his life in total oblivion, hidden under a veil. That beautiful soul died disfigured.

When I learned of his passing from this world, I cried with great pain: “Another one who was ground by the cell is gone!” But there were even worse cases! Kosta. R…, a minority from Mursia, was one of the most Albania-loving Greek speakers I have ever met. A man about thirty-five years old, as agile as the trout of Bistrica, where he had bathed since he was a child, with a special sense of humor, a rare singer, beloved and amiable with everyone, in short, a positive artist in every sense of the word. The most special phrase he used on every occasion was the expression “my dear.” But like all artists, he was fragile. Although he had faced duels with the State Security, had scornfully rejected every offer of cooperation in exchange for favors, and had pushed away comfortable corners with disgust, consciously choosing the “pickax,” as he liked to call it; in the Reps cells, the worms of the toilet defeated him.

It was the hot summer of 1969. The temperature in the sun at noon exceeded forty degrees. On one of these hot days, Kosta was cooling off with the water hose, with which we cooked on the concrete terrace. Born and raised by the river, he was so happy with the water that he didn’t care to watch the stream thrown upward in the form of rain, which hit the most savage policeman in the camp, Ndrecë “the skunk,” whose stench could truly be smelled an hour away. Ndreca, or “The Scorpion,” as we prisoners called him among ourselves, was the most negative policeman. He was a proverbial scumbag, with a tar-black soul and cruel to the point of sadism, vengeful to the point of madness; in a word, he was bitterness or a living poison.

When Kosta saw him, it was too late. “The Scorpion” was already soaked and screaming with rage. The apology that the “culprit” asked for inflamed him even more because he thought they were mocking him, due to his deformed personality, and as a result, the consequence happened: many policemen, attracted by “The Scorpion’s” screams, gathered, tied him up, and then crucified him on one of the poles of “The Road to Golgotha.” In the summer, the workday lasted beyond ten to twelve hours, depending on the will of the work police. Poor Kosta had to resist the hottest hours of the day in the scorching sun. In the absence of water, he would suck his own sweat. Late in the afternoon, when they removed the wires from his hands, they gave him a good beating and threw him into the cell. There, too, it was the same heat; his lips were on fire for a drop of water. Part from thirst, part from the blood he had lost, and his vision went dark. Blindly, in a corner of the cell, his hand grabbed a flask. As thirsty as he was, he drank it in one gulp, without caring if it was stale water or urine. It was just as warm.

Afterward, his stomach began to churn, he vomited everything he had in his belly, but since he hadn’t put anything in his mouth since morning, there was nothing to throw up. After a while, the cramps turned into convulsions, he expelled his bowels, accompanied by greenish, foul-smelling bile. He writhed and writhed on the floor, and when he realized there was no help, he started hitting the door with his head and feet. The clang of the sheet metal attracted the attention of the prisoners in the adjacent cell, who began to scream as loud as they could; “the officer of the guard, the officer of the guard!” Their screams and the banging of his head on the sheet metal were also heard by the soldier in the nearby watchtower. He gave the signal, and finally, the internal guards arrived. The first one at the door was precisely “The Scorpion.” When he opened it, he found poor Kosta unconscious, amidst his own vomit.

“Eh, friend, how do you like the bed!” he mocked cynically. “Ah-aah, but you’ve thrown up all this venom, man!” and he kicked him in the back. “An enemy only knows how to throw up venom from his mouth! Let him be, he wants to make a face!” But when he realized that the fallen man was not showing any signs of life, he called the doctor. Doctor Naim and Dilo were a few meters below, and they arrived at the cells in a flash. When they saw him in that condition, they insisted on taking him to the infirmary. But their insistence was met with the opposition of the policeman. “Oh God, he has vomited the whole world!” Dilo was astonished. “It smells like urine!” the doctor said, and they were forced to wash him where he was. “Ah, what a vile Greek this is, he wants to mock the Party by drinking piss!” the scorpion intervened. “But look, doctor, how he drank the whole flask of piss? He wants to get sick on purpose! But who does he want to throw it on, me! No, my friend, you’re going to die there, like a dog! We’ve seen so many like you, faithless Greeks with a knife in their belt!” Ndreca fumed. /Memorie.al