By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part thirty

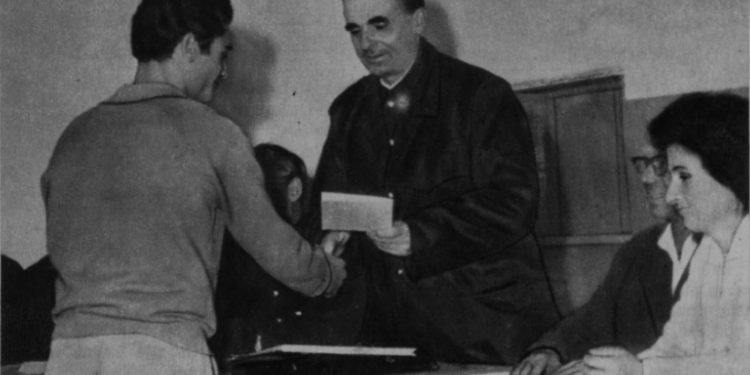

Memorie.al / I were born on December 23, 1951, in the black month of a black time, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief interrogator, Llambi Gegeni, the ignorant investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Internal Affairs Branch in Shkodër. They split my head, blinded one eye, deafened one ear, and after breaking several of my ribs, half of my molars, and the thumb of my left hand, they sent me to court on October 23, 1968. There, the wretched Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After they cut my sentence in half because I was still a minor, a sixteen-year-old, they sent me to the political camp of Reps on November 23, 1968. From there, on September 23, 1970, I was transferred to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, during the revolt of the political prisoners; four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we aspire to have. But on October 23, 2013, the General Director of the “Renaissance” Government issued order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for the “Dismissal from duty of a police employee.” So, Divine Providence intertwined with the neo-communist “Renaissance” Providence, and precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced, no more and no less, by a former State Security operative from Burrel Prison. What could be more telling than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by his former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

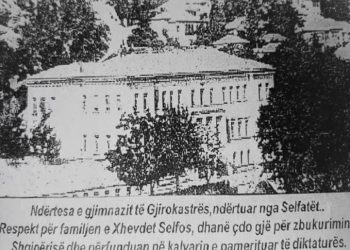

R E P S I

(The Forced Labor Camp)

Memoir

I looked up to where the sky should have been and added: “Thank you, Great God!” After the prayer, I collapsed like a wet chicken in a corner of the cell. I am especially grateful to Mark ‘the red-mustached,’ and I believe I’m not the only one; thousands of other prisoners throughout the years knew him and others like him. Even though they were few in number, they have remained in our memory as the standard for an honest policeman and a suffering Mirditor (a person from Mirdita). With that policeman, as well as a few others, I maintained a relationship of understanding, as much as there can be one between an executioner and a victim. I mean to say that policemen like him were rare; they performed their duty without abusing their power, they knew how to distinguish the law from excesses. In any case, in the Spaç camp, in the second zone, I had the opportunity to know another one later.

After two years, in the pyrite mines, fate would bring me together with another Mark. When the camp commander, Çelo Arëza, ordered him to tie up an old man who was being punished for not meeting the quota, Mark “the giant” responded with words that few executioners have ever uttered: “Friend, do you want to kill him?! I’ll kill him with my pistol, but I can’t tie up an unarmed man, let alone an old one!” And when the commander fumed: “I’m ordering you!” He replied: “Friend, an animal is tied up, a man is killed!”

But when the time comes, I’ll talk about Mark “the giant.” As soon as I was untied, I crossed the threshold, my tension vanished, and I collapsed in the corner where my feet led me. It was the first time I had been in the camp’s cells. I had no idea what they represented. The building, located at the northernmost edge, far from the sleeping barracks, beneath the guard watchtower, was an ideal spot for secret tortures. Even if you screamed, even if you cried out, no one would hear you, except for the soldier with the automatic rifle, who would be happy to shoot any political prisoner; moreover, he would earn a decoration and a fifteen-day leave.

During the investigation, they had moved me between several cells, but in the end, they were all part of the same building, even though they were located in the rear, in the damp basements. When I compared this hole to those in the investigative prison, the cells of Shkodra seemed like a walk in the park. At a quick glance, the environment here seemed horrifying, beyond horrifying. However, as these things would belong to the days to come, at that moment I was happy about the little I had: “Thank God you protected me from physical punishment and disfigurement!”

Curled up in the corner, I repeated one more time: “Thank you, Great God!” and I melted, like an ice structure under the heat of July. “God helps the honest and the believers!” a tenor voice boomed, piercing through the concrete floor. At that very moment, I understood that I wasn’t alone in the cell. A shadow was moving through the solution. It took a moment for my eyes to adjust to the darkness so I could make out an elderly man who resembled some grotesque caricatures from the magazine “HOSTENI” (The Goad); he had a large head with a thin neck on an extremely skinny body. He was so haggard that you’d think his soul was living in the ether.

It was the first time I had seen this face. As he was pacing, he looked at me, as if to weigh me, and in silence, he continued his wanderings along the cell. My clothes were dripping water; the spot where I sat quickly turned into a puddle. The slush that had flowed onto the floor from my muddy moccasins had left a trail of brownish clay, mixed with streaks of blood. My teeth were chattering. From the corner where I was huddled, I silently thanked my cellmate for not bothering me with idle chatter. But it wasn’t long before two simultaneous voices pierced the darkness: “Who are you?” the first one asked. “Who did you hit?” the second one. I heard them clearly, I could even hear their breathing, as if they were behind my back, but despite my determination to make out another person in the semi-darkness, I couldn’t distinguish anyone else besides the caricature that was pacing with his head down.

I quickly understood. I couldn’t see their faces because they were speaking from the adjacent cell, and a concrete wall and two iron doors secured with large padlocks separated us. I figured out that they had followed the conversation between me and Mark ‘the red-mustached.’ They had heard that there had been a fight and that the victim was a negative person, but they were asking to confirm it from my mouth. I briefly told them what had happened to me and who I was. Before I even finished, my unknown neighbors congratulated me. They were excited, bursting into praise, good wishes, and promises. “Just open your eyes now, you’ll have shadows on your back!” the powerful voice boomed at me again, making the ceiling of the cell echo. This loud, unsettling tone stunned me. I couldn’t believe that this caricature-like person, thin and frail, could have such an extraordinary voice. Then, when the echo continued even after he fell silent, my surprise multiplied.

It was interesting that from this thin, gaunt throat, full of veins and tendons that were clearly visible even in the semi-darkness, this thick, yet surprisingly gentle voice came out! “It takes great courage to face the devil!” he added again in the same tone. “These people are twisted, my friend!” he emphasized, in the mountain dialect. A shudder went through my heart, and my teeth, rubbing against each other, made a chattering sound. I was unable to stop this noise. The rattling of my jaws must have attracted the attention of my cellmate because he came closer to me and stared intently at me from head to toe. “Are you getting cold?” “Yes, very much so!” “But you’re all soaked, man! You’re dripping water as if you’ve been pulled out of a well!” he added when he saw the puddle beneath me.

“What can I do, they kept me tied to the pole for four hours!” I replied. “And today the skies have wrinkled, praise the Great God!” “Yes, it was a great storm!” I affirmed, shivering. “Alright, hang in there! In a little while, they’ll come to let us out for personal needs and they’ll bring us blankets.” “Will it take much longer?” “The devil buys their minds!” he took a couple of steps, and then added: “But until then, we have to move! Doesn’t just squat there, man, or you’ll freeze completely! Come on, get up now, and pace around the cell to warm up a little!” I got up sluggishly. I started to walk around the cell. At first slowly, then faster, and then, running.

The old man stood in the middle, like a coach training his athlete, while I circled this microscopic mini-field. But this field was not a circular square, but a rectangular space, ten feet long and six feet wide, and in the middle, instead of a wooden stake, there was a living being. I ran around this boundary for several minutes. Very soon, I felt the effects; my feet found their positions and no longer rattled as before. But my wet clothes continued to drip and weigh heavily on my body. It seemed the cotton filling was oversaturated beyond its absorption capacity, so it was releasing the excess in the form of a trickle.

Now somewhat warmed up, my clothes felt like a burden, so I took off the fleece jacket and threw it by the door. “You’re soaked, my boy, you need to wring out your clothes, one by one! Take off your moccasins and wool socks too, or you’ll get pleurisy!” the big-headed trainer, who resembled some grotesque caricature of a coach, ordered in a loud tone. Strangely, every word that came out of his mouth seemed commanding; perhaps because of that tone and that appearance, he resembled the ancient Mentor. I undressed without a word. I took off the denim jacket, my pants, and my wool socks. I was barefoot, only in my long underwear and T-shirt. “Take those off too!” the Mentor ordered.

I felt ashamed; I lacked the courage to undress in front of a stranger, especially a white-haired old man who commanded respect after every word. But the Mentor’s drooping eyebrows left no room for hesitation. I obeyed, pulling off the wool T-shirt that was stuck to my body, but… my collarbone hurt. A stabbing pain pierced my heart, a searing groan escaped my lips: “Oh, oh-oh!” I moaned. No matter how much I tried to suppress it, my teeth wouldn’t hold it back because they chattered, and the scream came out involuntarily.

“Come on, my man, don’t be ashamed, we’re men!” the old man, who had mistaken my exclamation as a sign of shame, tried to encourage me. “Besides, you’re terribly wet, you need to dry off! But there’s no place here, so you have to wring them out hard!” he added in a loud tone. When he noticed my hesitation, he pushed further: “You can’t spend the whole night shivering, my boy!” With superhuman effort, I also took off the rough poplin shirt. I was left in a tank top and long underwear. “Take that off too!” The Mentor gestured to the tank top. “Wring them out here!” with his index finger; he gestured toward the iron door. “Do you see this handle? Put them in and wring them with force!”

I approached the door. In the middle, I saw a kind of handle made of a rounded profile, about twenty centimeters long and wide enough to fit a hand. It seemed the craftsman had welded it there on purpose for such cases. Perhaps that welder must have been an old prisoner with long experience in cells. “Maybe he put that handle there to silently help his fellow sufferers or even himself”?! This thought came to my mind at the moment I put the tank top in to wring it out. I wrapped it around the iron handle, but as soon as I applied force to turn it, a sharp scream involuntarily came from my throat.

The pain in my collarbone from above my shoulder, multiplied, moved to my heart. The cell spun around me, as if I had been tied to the epicenter of a swirling fugue, and the fugue was spinning at a hellish speed, and I was thrown to the ground, unconscious. Today I am unable to remember what happened next, except that when I regained consciousness, I felt someone rubbing me with a swab. When I became aware, the old man signaled me to be quiet; meanwhile, he continued rubbing my injured collarbone. I felt somewhat relieved; the pain now seemed more bearable. “The murderers crippled you, but thanks to Holy Mary, you don’t have a fracture!” he said, as if talking to himself. “And your wrists, they’re bleeding too!”

I listened, but I kept my eyes shut because the masterful rubbing of those bony hands somehow relieved me. Perhaps this feeling was also caused by the kindness radiating from that stern face. “You’re beaten, man, you need to be treated!” and his skillful fingers carefully moved from the injured bones to the bleeding wrists. “I don’t know how I ended up like this, but they tied me badly!” I replied. “It seems so. But we’re in isolation here, my son, and there’s no one to take care of you!” he added with fatherly concern. “You must undergo a strict therapy!” he was now speaking likes a doctor. “And this is possible, even here where we are! Do you understand?”

I didn’t know how to take it, as a mentor’s order or a parent’s concern? I was unable to make the distinction. At that moment, he resembled both a surgeon giving advice to a patient and a worried father. Whether it was his well-chosen words or his professional competence, he lacked nothing, neither as a father nor as a doctor. “Excuse me!” I interrupted. “Are you a doctor?” “No, I’m not a doctor, but a priest! A Catholic priest!” he specified further. “What is your name?” “They call me Dom Mark Hasi!” “Ah-ah-h-h!” I interrupted in surprise, because I had indeed heard the name of this stoic priest, but no one had ever told me about his special abilities in medicine. “But what does it matter, my man, now you need a doctor most, and I know a little something about medicine. In these conditions, we’ll do what we can!”

He pulled my wet tank top from the corner, which was hanging like a rag, and tore it into pieces. With the strip he created, he began massaging from above my shoulder, passed it under my armpit, and then once more around my chest, where he wrapped it as best as he could. He had bandaged me masterfully, because right after that, I felt very different. The pain still existed, but it was lighter, more bearable, sweeter, if I can put it that way. Perhaps the feeling of kindness prompted the thought in my brain that someone was taking care of me, even there, at the bottom of skewer.

“God must be Great, since he brought this blessed priest my way,” I said in my mind, while with my mouth, I said: “Thank you for the care, Dom Mark!” “We do what we can!” he replied modestly. “You took away my pain! You must be a saint!” “I am a soldier of Jesus Christ!” “Without a doubt, I will repay you someday!” “Come on, man, here where they’ve put us, anyone would do this for anyone! I myself am a priest, and I have spiritual duties, but we got caught!” again with excessive modesty. The work I couldn’t do, which was wringing out the soaked clothes, the priest finished. The puddle of water below the door grew larger.

The clothes were wrung out, but the clay slush would dry on them because there was no place to shake them, let alone wash and hang them to dry. More than an hour had passed since they had locked me in there, when from outside the cell, the rattling of the bolt was heard. They opened the door. Under the light of the searchlight from the watchtower above, I saw two policemen and a prisoner in the hallway. The prisoner was looking at me intently. He was staring me right in the eye, as if he wanted to tell me something.

I only knew the camp’s assistant cook by face; I saw him whenever I came to get my ladle of soup, but nothing more. Usually, I didn’t get close to the people employed in the rear, and especially in the kitchen, because people spoke ill of them, and public opinion did not view them favorably. They were generally considered spies and collaborators of the operative or simply servile to the head of the technical office. When I got my food, I didn’t exchange words with them, but I stood in line at the cauldron, extended my bowl when I got close, and pulled it back as soon as they put the soup in, then I would go away to slurp it wherever I could, either at my bed or in some corner.

I had never returned for an extra ladle, even though hunger was gnawing at my insides. I had been fed the idea that to maintain your dignity and integrity, you shouldn’t go back to the cauldron for a second time. Meanwhile, in the camp, I met many hungry people who had made it a habit to stay around the kitchen, waiting for a second portion of this disgusting stew that remained at the bottom of the cauldron, or to scavenge for a piece of discarded bread. These prisoners without help, without families, or abandoned by their relatives, were trying to survive. Although returning to the cauldron was seen as an insult, these hungry wretches had swallowed their shame because only in this way could they ensure their existence.

The assistant cook had placed the black pot on a wooden bench. Beside it, a large, dirty canvas bag whose original color was unrecognizable. The priest approached the bench with his bowl in hand, waited for them to ladle out the slop, and returned to the cell. He placed it on the floor and went toward the toilet to take care of his personal needs. One of the policemen whispered something to his friend that I couldn’t catch because I was still shivering; then the other one moved to the far end of the cell to keep an eye on the bathroom.

“Hey, friend, have you peed inside?” the policeman asked, surprised, when his shiny boots landed in the puddle near the door. “What is all this water, man? Hey, friend, do you want to get your food?” he turned to me, pointing his finger at the assistant cook: “Come on, then, move!” “I don’t have a bowl!” and I stopped at the cell door with empty hands. “Come on, I’ve brought you some!” the prisoner jumped in and, after untying the drawstring of the bag, pulled out a bowl and something else that I couldn’t see because the policeman was blocking my view.

“Hurry up, friend, we don’t have time to wait for you!” the other one, from the corner where he was watching, snapped. I put the fleece jacket, which was still dripping, over my shoulders and approached. At their feet lay a package wrapped in cement paper. “Take them, they’re yours!” With one hand, the assistant cook handed me the bag and the packaged items, while with the other, he gave me an aluminum bowl filled with soup. “What are you giving him, friend? What’s in that bag?” the policeman who was watching from the corner of the cell jumped in. “Nothing, his dishes and blankets!” As he spoke, the prisoner turned pale and secretly gave a quick glance to the other policeman.

I smelled something; this lightning-fast look implied a conspiracy, so I didn’t hesitate; I snatched the bag from his hands and headed for the door. “Wait, friend, I want to see them myself!” “Leave him alone, Preng, I’ve checked them myself!” the other policeman cut him off. “Come on, then, move, the wind is drying us out here!” he fumed at me. “What kind of a person are you, man, you’ve been in this job for a lifetime and you’re still an idiot!” he taunted the assistant cook. I returned to my corner with what they had given me. “Hey boy, aren’t you going to the bathroom now, or do you want to stay up until tomorrow morning? Are you listening to me, friend?” Police officer Prenga addressed me.

This order brought me back to my senses. I remembered that I hadn’t gone outside since before they tied me up. “As you command!” I replied briefly and headed for the bathroom behind the cell. Meanwhile, Dom Mark, who had finished his business before me, took the blankets from the bench and a broom made of heather branches, and began pushing the accumulated water outside the threshold. He finished and went back inside, and I followed him. The policemen locked the door with a bolt and a key and headed to the neighboring cell.

I had a busy day, with events that followed one another. In a segment of just a few hours, I had to experience several phases: first, the clash with the pederast and reaching a state of savagery; then, the total confusion from the event that I had never even considered could happen, which was to turn from a victim into a conscious murderer; then, being crucified with barbed wire for over four hours behind the pole on Golgotha, in the freezing cold and relentless rain; finally, a supportive policeman who didn’t tie me with pliers and this blessed priest who came to my aid at the most critical moment; now a prisoner whom I had just a short while ago considered unworthy to talk to, and again, another supportive policeman! All of these were too much for one day!

However, my growling intestines brought me back to the bitter reality. I grabbed the bowl with the stinky soup and gulped it down in one breath. The leek rings almost choked me, but they warmed my stomach. I collapsed on the floor. I was shivering. The wet fleece jacket on my shoulders made me feel even colder. Five minutes of rattling were enough for the shivers to return, my teeth chattered more intensely than before. My heart was fluttering in my chest like a swollen bird. When the priest saw me shivering, he ordered me: “Throw that wet fleece jacket aside! Open the bag and take a blanket and put it on your shoulders!”

I didn’t wait for him to repeat it. My eyes found the dirty bag in the darkest corner. With my trembling hands, I untied the drawstring of the bag and, after widening it with my fingers; I turned it upside down and shook it to get the items inside to fall out. But they were packed very tightly and wouldn’t fall, so I put my hand in, grabbed a corner, and pulled. When I pulled them out, in one hand I was left with a roll tied in a military style with string, while in the other, the dirty bag. I tried to undo the tangled knot. Deliberately or not, the knot was tightened excessively, so much so that I couldn’t untangle it even with my teeth. The priest helped me, and finally, we managed it. I grabbed the corner of a rough piece of cloth and wrapped it around my shoulders. The roll unraveled on the floor, and a bundle of other clothes scattered at our feet.

The priest picked them up one by one; they were some undergarments, among them a vest and a pair of wool pants, a thick-thread wool sweater, a pair of socks of the same kind, and another smaller package wrapped in cement paper. The voices outside had died down; the policemen had finished the ritual with the other prisoners in the neighboring cell and had left.

“You have golden friends, get dressed now!” the Mentor ordered and at the same time congratulated me. Still dazed by the unexpected sight before my eyes, I mechanically threw the wet fleece jacket by the door; I took a shirt, put it on, over it a wool sweater, and over that, a vest with wire buttons. I then untied the drawstring of my wet long underwear and put on the dry ones, over them the wool pants, and finally, the wool socks.

The warmth spread throughout my body, from the periphery to the inside, my blood began to boil in my veins, and my heart settled down. What a delight I felt at that moment, my soul was at peace! Life had triumphed! I unwrapped the paper package; inside, two portions of bread, cut lengthwise. “Oh God, bread! Two daily portions of a worker!” I couldn’t believe my eyes. Someone had voluntarily given up their food for two days for my sake! Others had gone to great lengths; they had deprived themselves of the clothes on their bodies! But someone had risked even more, by taking on the transport, all the way to this mouse hole!/Memorie.al