From KRISTAQ JORGO

Part Two

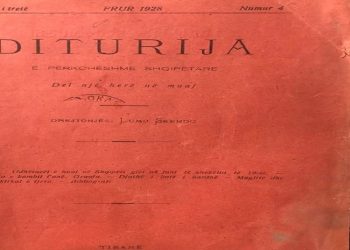

Memorie.al / Over the years, it hasn’t just been the figure and complex personality of Konica that have been the subject of debate, but also his creative work. For example, “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” a work considered to be left unfinished by the great thinker, serves as a model. The following article is an attempt to prove the opposite. Faik Konica’s first biographer, Qerim M. Panariti, would write in 1957: “His most powerful work is without a doubt the novel Dr. Gjëlpëra, which reveals the roots of the Mamurras drama,” where he performs a merciless anatomy of Albania’s social and economic diseases. This satirical work began as a series of articles in “Dielli” in 1924, but it was interrupted after Konica aligned himself with Zog.

Continued from the previous issue

But, if the work as we know it is finished, how could we then explain the note at the end of the last fragment, that of November 1, 1924: “to be continued in a future issue”? Precisely in the days when the publication of “Dr. Gjëlpëra” ends (as we believe) or is “stopped,” the trial for the organizers and murderers of Mamurras reopens in Tirana.

Konica resumes writing about the “drama,” and even publishes the “Official Report of the investigations into the Mamurras event” in several issues of “Dielli” in December 1924. Could Konica have had the idea that everything he wrote about this topic and this report itself, should be conceived as somehow related to the work, if not as part of it?

But here we are at the limits of genuine speculation. Let’s try to imagine more similar reasons that could justify our thesis that, even despite the note, “to be continued in a future issue,” we are dealing with a work that, from an authorial point of view, is complete. And there are several possibilities:

The note at the end of the last fragment is an error by the editor or typesetter, or in other words, his first readers, since, as we saw, in itself and from a superficial glance, it does not have any kind of concluding nature; the note is part of the text, intended by the author, who, through this virtual continuation of the work, may have wanted to make the reader aware that a civilizing action, such as that of Dr. Gjëlpëra, cannot and should not “end.”

The note is an elegant provocation that Konica may have had the whim to make to the public’s horizon of expectation. The note truly announces a continuing and more conclusive fragment of the work, but which – and Konica may have reached this conclusion after the release of the November 1 issue – would in a sense make the work mediocre.

If all that has been said so far proves to be fundamentally unimpeachable, how can an error made so many times be explained?! There are, in our opinion, two reasons, one general and one specific.

The general reason is, among others, a consequence of what we have named the complex of superiority of the meta-literary mind over the Albanian literary mind, which is close to another complex that of the superiority of the present-day mind over the earlier Albanian mind.

The reason, or rather the specific justification for the repeated error, is related to a radical change in the perspective of reception: the historical reader knows almost everything about the Mamurras drama, but almost nothing about its roots, in the sense of the deep historical, political, psychological, etc., causes that nourished it, just as they have nourished and continue to nourish hundreds and thousands of small and large Albanian dramas.

Meanwhile, the reader of today knows almost everything about these roots, but almost nothing about the specific “drama” of Mamurras. It is natural, under these circumstances, that the historical reader does not expect anything about this drama, while the reader of today seeks to learn almost only about it from the work. In other words: for the historical reader, the Mamurras drama is present in the pre-text (title), absent in the text, and omnipresent in the context.

For the later and present-day reader, the Mamurras drama is present in the pre-text, absent in the text, and even more so absent in the context. In this dual textual and contextual absence, is the source of the persistent demand of today’s reader and scholar, who necessarily expects the “appearance” of Mamurras in the work?

Let’s put aside Michel Butor’s thesis, according to which incompletion is not a characteristic of one or a few given works, but an incoherent feature of modern literary work. Let’s accept as a complete given the myth or half-truth that Faik Konica left us only with unfinished works!

One fact can in no way be denied: Konian texts, even the “unfinished” ones, or those that are truly so, are paradoxically elements of a finished macro-text.

We are talking first and foremost about the coherence in time of Konica’s general worldview. This statement of ours – we are aware – is in blatant contradiction with the prevailing opinion, which precisely underlines incoherence as one of the fundamental features of the author of “Dr. Gjëlpëra.”

Let’s be clear: Konica demonstrates masterful incoherence, but, and this is essential, in matters of second and third importance. In first-rate matters, and this is what we should consider, his coherence may have few peers in the modern history of Albania.

Which are those Albanian personalities who can “boast” that they have insisted repeatedly and steadfastly, for so many years or decades, to root the same idea in the Albanian world?: “I have said it for twenty-eight years in a row and I repeat it once more: Albania needs a moral revolution, a change of values, a new understanding of good and evil, an understanding not only new but stronger, deeper, and more alive.” (“Dielli,” July 19, 1924, p. 4).

From the perspective of this fundamental coherence of worldview, it can be said without exaggeration that during his life, Faik Konica materialized, as few others in the Albanian cultural world, in general terms, a single work, a corpus (with a strong internal coherence) of parts, which are linked to each other and to the whole by dense intertextual relationships.

To cite just a few examples: “Lulia e malit,” the “tale” written about three decades before “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” has essentially the same plot structure as it, it is a kind of architext of it, just as “Një ambasadë e Zulluve në Paris” and “Shqipëria si m‘u duk” have strong connections with “Dr. Gjëlpëra” – and this has been noted.

Konica takes care to conclude his single literary-life work, even textually, with the “Testament,” which also speaks of a return – just as Tosku (“Lulia e malit”) returns with a civilizing mission, as Plugu (“Një ambasadë e Zulluve në Paris”) returns, as Dr. Gjëlpëra returns – now their father himself and definitively returns.

It is undoubtedly a sign of genius, not so much the rigid conclusion of the parts, but the open conclusion of the whole, the parts of which appear as variants generated from a single essential matrix.

The basal coherence of the whole, on the one hand, has allowed Konica the “luxury” of not worrying too much about “finishing” his works, and on the other hand, this coherence has the ability, in a sense, to “finish” even the “unfinished” ones. Based on the above conclusions, two words now concerning Konica’s place and his action in the context of the Albanian whole.

First of all, it is worth seeing what the Albanian whole, or entity, is for Konica himself: “The English have a popular saying, that a person who is in the middle of a forest cannot see the forest but only sees some trees. A true saying. The forest can only be seen by those who are outside the forest. Observers like the undersigned, which live far from Albania, may be confused in local ‘details’ about Hasan or Gjergj, but they see the whole (l’ensemble) much better and more clearly than the insiders.

Do you know what Albania looks like from the outside? It looks like a muddy, troubled, and dark place, without a guiding light, without specific goals, where everyone fights for his own bone, where interests fight against interests, and where vileness and mud scream that they are noble […]. That’s what Albania looks like from the outside. And if I am not blind, that’s what it is. A tragedy without a name.” (“Dielli,” July 29, 1924, p. 5)

Yes, it is true, in other words, a battered boat. However, here Konica errs. He errs, because Albania is not just what it “is.” Albania is also what it has been; besides this, Albania is, for example, also Konica.

Albania is not, therefore, just the battered boat. Albania is the battered boat which – no one knows how – has withstood a two- or three-thousand-year-old storm, and which – again no one knows how – a thin but unbreakable thread holds tightly connected to the highest rock of civilization. This is Albania, in its triple nature: battering, resistance, orientation. Extreme battering, indestructible resistance, superior orientation.

And as if this were not enough, an individual, an idea, an action in the Albanian world, not rarely, to say often, helps at the same time both the battering, the resistance, and the orientation. Under these conditions, it remains to be determined, although it is not easy, what the dominant function of the individual, the idea, and the action is in this triple and confusing Albanian world.

Naturally, not the function of the idea, the individual, the action in itself, since a function in itself does not exist, not even the function of the part in relation to the part, because this shows a deformed picture, but their function in the whole.

Konica, and this is one of his unique qualities, is a partisan not of syncretism, but of the differentiation of functions. His function is the most difficult one, the function of orientation, of the unbreakable thread that keeps the battered and resisting boat tightly tied to the highest rock of civilization.

“And Faik changes face” – yes, it’s true; “Yesterday he cursed, today he praises” – that’s how it has been; “he puffs his cheeks and trumpets / that tar turns white” – you can’t argue with that. All of these are truths. The point is that these are truths more emotional than rational, that the part tells the part, for the time being, within the battered boat that survives and tries to orient it.

It is enough to broaden the horizon, to get out of the battered boat, to move away from it, to grasp the full view of the triple Albania from a distance and from above, of Albania-in-the-world-and-in-time, and then we will understand that in the perspective of this whole, Konica is not simply a personality, even “one of the most brilliant sons of Albania,” as defined by Noli; he is a component or rather a dimension of the Albanian world and civilization.

Without him, Albania of the first half of the 20th century is mainly battering and resistance. Not only with him, but primarily with him, Albania of the first half of the 20th century is battering, resistance, orientation. The battered boat that is inevitably tossed, swayed, pulled, and spun from one side to the other the thread that connects it to the highest rock of civilization; it might even break it.

Since the thread has chosen the position of unwavering stability, since it will not and cannot yield, it will naturally experience all these tensions.

Most of the endless complex of vices, sins, and mistakes attributed to Konica, viewed not from a personal-psychological perspective, because that tells us nothing, but from a systemic perspective of the Albanian whole, is nothing but the inevitable counterbalance of his position of unwavering stability, his single idea, his life’s dream, the function of his work, which happened to be not just his dream, his work, his idea, but a dimension of the Albanian world.

We tried to prove succinctly that “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” from a plot perspective, has nothing to do with the Mamurras drama, that its so-called interruption did not happen on December 24, 1924, but two months earlier, that this fact has no connection whatsoever with Konica’s so-called change of political course and his alignment with Zog, that, since the work is proven to be finished three months before the publication begins and for a number of other literary and extra-literary reasons, there is no way it should be called unfinished!

That in terms of genre affiliation – we did not dwell on this point – the work should not be rigidly evaluated, as it is an excellent example of the dynamics and complexity of the evolution of the genre system in Albanian literature, that all the components of the work, at all levels, a detailed examination will be able to prove organically functional, that Konica’s so-called serious flaws appear important only if they are examined through an unimportant perspective, that “Dr. Gjëlpëra,” like all of Konica’s action in the Albanian world, finally and in summary, is not an unfinished work, but a finished one, even something more, a perfect one.

This last word brings to mind once again Qerim Panariti, the man who first started that story of the repeated error of the repeated error, and who, as if to atone for that sin, left us the most lapidary description ever made of the father of Dr. Gjëlpëra, “the most perfect Albanian,” Faik Konica. / Memorie.al