From Prof. Assoc. Dr. Gjergj P. Titani

Part Five

Memorie.al / In this article, we are publishing a long interview with “People’s Artist” and “Grand Master of Labor,” the distinguished composer Dhora Leka. The conversation with her began a long time ago, but almost nothing has been published because her desire was to finish her memoirs, summarizing them in a special book titled; “Moments and Impressions from My Life.” The book has been revised several times and has been cross-referenced with both archival documents and her family’s personal archive. Today we are publishing the first part of the presentation with the distinguished composer, which will continue for several issues.

Continued from the previous issue

THE FAMOUS ARTIST WHO WAS SENTENCED TO DEATH

Mrs. Dhora, what happened with your mother?

A few months after I was interned, my 80-year-old mother was brought to me from Berat. Here’s what had happened! They demanded the room she was living in, and finally they took it from her. “It’s nothing, my daughter,” my mother said to me when I hugged her. “They want to throw me, an 80-year-old woman, out on the street. They don’t care that I was the mother of four partisans and sheltered in my home all those who are great today. Where can I find them to spit on?”

So, they threw my mother out onto the main road and told her, “Go and live where your daughter is.” And that’s how they indirectly interned my mother as well. With my mother’s arrival, I parted ways with the good Xhina and went to another barrack, across from the only multi-story building. Regardless, despite the hard physical labor, I found the strength to weave the rebellious verses of revolt. The day after I left Berat, my terrified mother burned all my poems.

THEY BURNED MY “REBELLIOUS VERSES”

They burned my “rebellious verses”

on a cruel night

that I awoke in the cell.

Poor Mother knew

what awaited me

for “The rebellious verses”

(if they fell into their hands)

they would make a sacrifice of me!

But the news of the burning

heavier than a bullet

pierced my chest!

Oh, Mother!

Poor Mother

what a crime you have committed

You don’t understand this,

you don’t know

You burned “Harlem,”

“the silent riverbed”

and left the PORTRAIT

of “the sick one”

forever half-done,

You burned “Macbeth,”

the “Bells” whether you want them or not

will not be heard,

you burned them all,

oh, the verses of command

that cannot be counted…

I tire my memory

now night and day

to bring the rebellious verses

back into the light

but “the Dead River”

where I live:

-Don’t waste time

it tells me

Write new verses

and more rebellious ones

I will dictate to you.”

Internment in Seman, June 1968

Do other words really need to explain what happened? Of course NOT.

Were you upset that your mother came to you?

Is that a question?! Are there words that can describe both pain and joy together?! No! There are not! My mother had risen us, had followed us in the war, in internments, she was my inseparable, tireless, brave, and self-sacrificing companion, who accompanied me even in this barrack, where whatever was outside came inside.

So, I was both revolted and happy at the same time. My mother was with me; that was the most important thing. She was my calm, my courage, my support, my comfort- she was everything.

After New Seman, where were you sent?

It seemed my persecution had to experience all of its “varied” forms. From Seman, I was assigned to live as an outcast in the city of Fier. The living conditions were relatively better. I was assigned to work as a seamstress. The years flowed one after another.

“Under the weight of violence,” as my friend from my youth, Todi Lubonja, accurately describes in his writings, until February 1973, with a minimal pension of 3,500 ALL, I retired.

I had turned 50 years old but had not received anything from the pension for veterans of the National Liberation War because, according to the law at the time, as an “enemy of the people,” we were not entitled to it. Although I was 50, I never stopped my creative work.

During my time in Fier, my main creative work in music, besides poetry, was the opera “To the Mountains for Freedom,” dedicated to the “People’s Heroine,” Zonja Çurre.

However, unexpected things never stopped happening to me. The years I lived with my mother in Fier were relatively the easiest years of my long persecution. On this occasion, I want to mention my metaphorical saying: “When black clouds covered the sky of Tirana, storms and lightning erupted everywhere.” I felt the storm that had broken out in Tirana, even in Fier.

It was December 1982, when the terrible vortex of the dictatorship’s crimes did not spare even Mehmet Shehu. On January 13, 1983, I was interned in Sheq-Marinëz. On the same day, my sister was also given the same internment order for Sheq-Marinëz, along with her children. Tuk Jakova had died 24 years earlier in the hospital of the Tirana prison under very mysterious circumstances. In Sheq-Marinëz, with my sister and her children, we stayed until the overthrow of the dictatorship.

What are your impressions of Sheq-Marinëz?

My life in the Sheq-Marinëz internment had the same troubles as the internment in Seman. By then, the family had grown. My sister and I were pianists. The children had grown up. The boys and their wives worked in heavy agricultural labor. Children were born into our family as well. And there is no greater pain than to see your child’s children being treated cruelly.

And for a child to experience the weight of violence. I remember one day, my grandson, Lulëzim, came. He came crying: “Grandma, why do the village children call me; ‘go away, traitor’s grandson’?! You told us that Grandpa Tuku was a partisan. Oh, I love Grandpa so much! But what did they do to Lila; do you know what they did to her? They put s**t in her mouth!”

The child spoke with sobs, and tears flowed without stopping. What was said to the children?! What fault did they have for being born into internment and being treated as such?! No fault! The pain was nothing compared to the insult. I have never felt more spiritually and morally devastated than when I passed by the stairs and the children, singing my song, “Those striped mountain tops,” threw stones at me, shouting loudly; “You old woman, you interned old woman, enemy, Ballist, rotten,” etc.

And what fault did these children have, and what fault did their parents have, what fault did the teachers have who mutilated their souls in this way?! They had no fault at all! The great and unforgivable fault lies with the dictatorship and the dictators. There is no need to dwell further on the internment in Sheq-Marinëz. Internments in Albania during the dictatorship were endless suffering. To describe them would require volumes, many volumes. On January 13, 1988, when we were expecting our release, I was informed by the Fier Internal Affairs Branch of another 5-year term.

What about today, after so many years…?

Today there is much speculation in the written and television media about the course of events and specific individuals. More than anyone, these speculations are felt by those people who went through the arduous calvary of the over 50-year-old dictatorship. They are the authentic witnesses of this holocaust.

And it is a civic dedication, a necessary duty that these distortions staged by the specialized organs of violence do not violate the rights of those who have suffered and that the light of truth is shed, especially in judicial processes. The files of the judicial processes are authentic. I will tell you about a specific case that happened to me in the trial of the “hostile group” of Kadri Hazbiu. Here is the truth!

It was still the beginning of my internment in Sheq-Marinëz, in 1983. I later learned that Kadri Hazbiu had been arrested. From the day Tuk Jakova, my sister’s husband, died under such enigmatic circumstances, all of his relatives were tormented by this fact. And we constantly tried to find data to uncover this enigma, and the signals were not lacking.

At the moment of his death, Filip Jakova, Tuku’s brother, who was interned on the island of Zvërnec, told me: “Listen, Dhora, I am dying, but I am leaving you a great trust, which happened years ago. Tuku did not die in the hospital from appendicitis. That’s what they say, but the truth is completely different.

One day, an officer of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, who was serving at the prison hospital at the time, came to my office, and after he closed the door, he said to me; ‘On a man’s honor, I’m telling you that Tuku did not die simply from appendicitis, but he was poisoned with an injection.

And after they sent him to the morgue, Kadri Hazbiu, who was the Minister of Internal Affairs at the time, went to see his corpse personally. At that moment he said: ‘This is how you ended up, you dog!!!’

Dhora, never forget this information! I believed the officer’s statement because he was a highlander from our North and his dialect was like that. He asked for my ‘man’s honor,’ and precisely for this reason, I have kept silent until my last moment.

When Tuku died, Kadri Hazbiu informed Enver Hoxha when he was in one of the Political Bureau meetings and told him: ‘Comrade Enver, today Tuk Jakova died in the hospital from acute appendicitis.’ Enver, at this news, burst into shouts and said: ‘Listen, Kadri, they will accuse us of killing Tuk Jakova; how can a person die like that in a hospital from a simple appendicitis’?!

But it seemed this was the acting game he knew how to play very well in front of the other members of the Political Bureau. Nevertheless, I have kept this trust from Filip for a long time, because the earth does not swallow a promise, and I had not even told my sister. She was extraordinarily shaken when she found out about this.

More specifically…?

We continued the conversation all night. We listed all the information we had learned about Tuku’s death. In the end, I told my sister that I wanted to bring this fact to light and had decided to denounce it in the judicial process. “Will you do that, my sister?!” “Yes,” I said. “I will do it. I have the courage to do it because I owe it to Tuku. Do you remember what he told me in Berat when we finished cleaning the house?”

“Thank you, Dhora, thank you very much; I never expected it from you. When I was there,” and he motioned upwards, “I never did anything good for you. I’m sorry that maybe you will have some bitter hardship because of me…!” And after that shocking moment, we hugged, and she, in tears, kissed me.

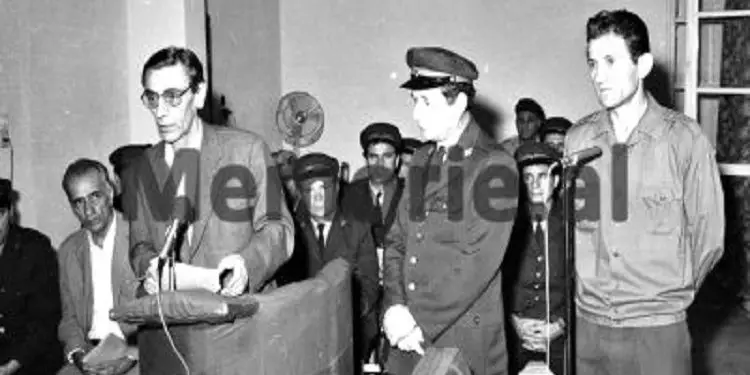

Let’s talk a little about you, how did you go to Kadri Hazbiu’s trial?

During the days of Kadri Hazbiu’s trial, I got permission from the Fier Internal Affairs Branch, went to Tirana, and asked to meet with the person who was dealing with Kadri Hazbiu’s case, telling him that, “I have something very serious to denounce.”

Shkëlzen Bajraktari was introduced to me, and he told me that he was the investigator of the case. After he asked me why I had come, I told him the reasons I explained above, and he said to me: “Yes, you can come!” On one of the days of the trial, I was also notified, and I came with my desire to testify and accuse him of the serious crime against Tuk Jakova.

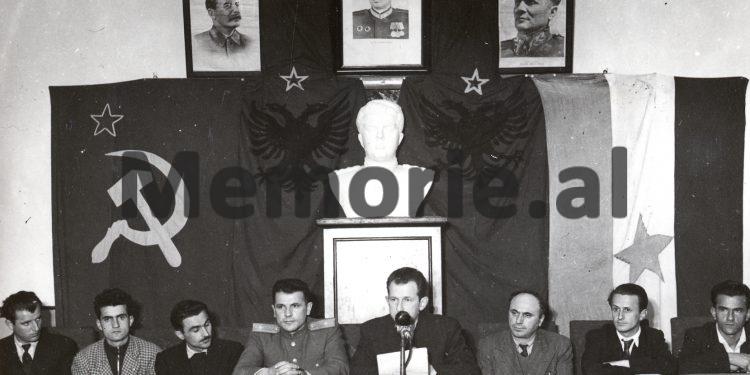

The trial was held in the Tirana prison (Department 313), in an improvised hall. Specifically for us outsiders, to get there, we had to pass several iron gates, guarded by sentries and locked with keys.

I remember that in my speech before the court, I presented what I have told you above during our conversation. I ended my accusation by addressing Kadri Hazbiu… “Regardless of what you charged Tuk Jakova with, you had no right to take his life…!”

The Chairman of the Special Court, Arianit Çela, addressed Kadri Hazbiu, asking him: “What do you have to say, defendant?” Kadri Hazbiu stood up and said neither yes nor no to my words. He only said these words: “Let it be verified,” and sat down. After that, Aranit Çela turned to me and asked: “What do you want with what you said here?” “Nothing! I came to denounce a crime.”

After this, the chairman motioned for me to leave the courtroom. In all cases, when films or articles have been published or shown about the trials of Kadri Hazbiu’s group, the film or writing has been interrupted precisely when I said in a loud voice: “That I came here to denounce a crime!”

Based on my specific case, I am convinced that this case of inaccuracy or distortion is not the only one for which I am extremely indignant. / Memorie.al