Memorie.al / The former head of the Propaganda Branch at the Book Enterprise talks about her work under the communist regime. The organized fairs abroad, where the stand with the publications of Enver Hoxha’s works was the best-selling one, the interest of foreigners in them, and their distribution in every city of Albania. At the same time, she shares memories from life near the former ‘Bloc,’ as the niece of former Prime Minister Adil Çarçani, from the latter’s appointment to this post, to the possibility of the elimination of his predecessor, Mehmet Shehu.

Today, they have ended up on the sidewalks of the former “Bloc,” exactly where once upon a time, the high leadership used to stroll. We are talking about the dusty works of Enver Hoxha, with that unmistakable red or burgundy cover and golden letters, which after being cleared from the library of some house that couldn’t possibly lack them, especially during the years of the communist regime in our country, have taken their place in the corners of the capital, being sold at the price of today’s market.

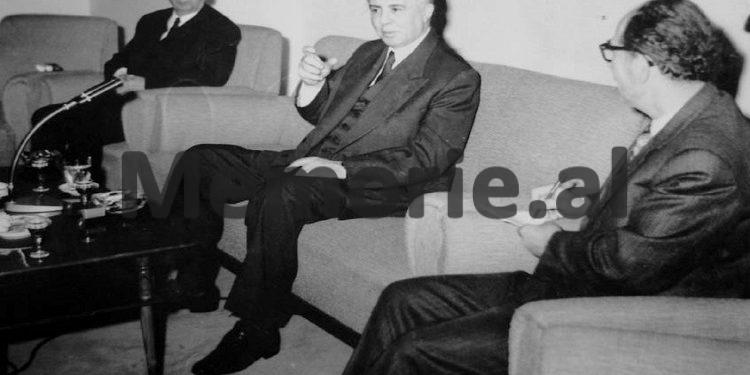

However, in those years, the path to publishing such a work was not simple, even though there was an entire enterprise for the production and propaganda of new books, and mainly those that bore the signature of the dictator and the other retinue that followed his vision of leadership. In her capacity as head of the Propaganda Branch at the Book Enterprise, Natasha Bocaj, the niece of the country’s former Prime Minister, Adil Çarçani, had the primary role of ideological “injection,” through the publications of Hoxha’s works, as well as those of other leaders.

The most serious work was done especially in the various international fairs that were organized, where posters and publications of Enver’s works were always exhibited at the head of the stand, while the others followed behind. According to Natasha, the interest of foreigners in the dictator’s works, translated into foreign languages, was extraordinary, so much so that not a single copy was left to be returned to Albania, and at the end of the book fair days, the Albanian stand turned out to be one of the most successful for the number of copies sold.

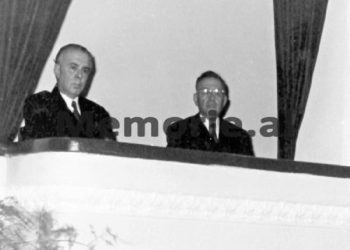

Today, Natasha tells not only how the sector she led functioned but also about the special relationship with her uncle, Adil Çarçani, especially after his appointment as Prime Minister, immediately after the sensational event of December 1981, the “suicide” of former Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu. As the daughter of Sadik Bocaj, the head of the Statute at the apparatus of the Central Committee of the Party of Labor of Albania, with his role of selecting and excluding from the Party ranks, individuals who were initially classified by the word of Enver Hoxha…!

Ms. Bocaj, let’s start by talking about your relationship with your uncle, the country’s former Prime Minister Adil Çarçani. What was your connection with him like?

It was an excellent relationship, not only for the fact that my uncle was a wise, humble, and hardworking man, but above all a generous individual with a big heart. I am the daughter of Adil Çarçani’s sister, and to be the Prime Minister’s niece in those years was not a small thing.

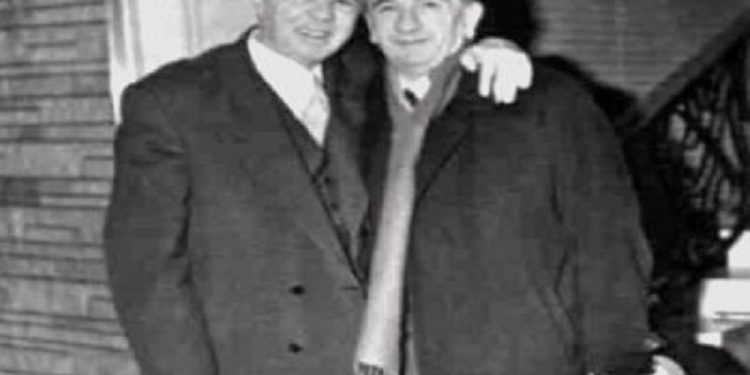

Although we didn’t enjoy great privileges. We lived in a house near the “Bloc,” where the villas of the leadership were located, so we were very close to my uncle, while a privilege I remember even today was enjoying the three summer months in the officials’ holiday homes, mainly in Vlora, where we stayed as a family. And for many years in a row, we also had a governess, a woman who cooked and cleaned the house for us; this was not because I was his niece, but because my father was also a person with a political position. When Adil was appointed to this post, immediately after the sensational event with his superior, that is, the “suicide” of Mehmet Shehu, I was almost 40 years old.

A very positive opinion circulated about my uncle, not only among the people but also in the category of leaders with whom he was connected by daily work, so much so that I often heard them express how it was possible that “the wolf” (Mehmet Shehu) and “the lamb” (Adil Çarçani) worked together. So, for a man as rough as Mehmet to get along with a gentle person like my uncle was a great achievement, which made them both value each other very much even in difficult days.

How was the suicide of Mehmet Shehu received in your family, and then in Adil’s?

Everything was so unexpected. Hearing from my uncle, but of course, I had known Mehmet myself, because of the many visits he made to our house, often with Enver Hoxha, I knew that he was an iron man. And it was unimaginable that he would point a pistol at himself to commit suicide.

The different theses that circulated highlighted the possibility of his elimination, not even by foreign agencies, but by those within the leadership clan, which then concocted the whole story of this unusual event. Someone who wanted to take his place, for sure. I cannot mention specific names…!

Natasha, your father also had a position in the ranks of the Party of Labor of Albania, a member of the Central Committee, right?

I am the daughter of Sadik Bocaj, who was a member of the Central Committee of the Party of Labor of Albania, more precisely the head of the Party’s Statute. His beginnings were those of a fighter, near the First Assault Brigade with Mehmet Shehu, and then he moved to the Army Division. My father was appointed to the Central Committee in 1953, and his duty was of special importance. Only with his signature could possible candidates for delegates, for members of the Communist Party, and other high leaders be accepted into the Party.

His role was more than selective, because of course the candidacies had been determined beforehand by Enver Hoxha himself. But, if there were “snags” in the biography or involvement in some event that violated the “party’s ideal,” my father was the first person to make the exclusion from the Party ranks, after things were proven before the dictator Hoxha first, of course.

In which of these leadership decisions was your father involved?

Because of his commitment, he was naturally present at all the meetings organized by the debaters, that is, the members of the Political Bureau, who unanimously made decisions to exclude a certain functionary from the Party or eliminate them…! One such person was Beqir Balluku, who was sentenced with the “putschist group” in 1974.

In that meeting of the Plenum of the Party’s Central Committee, it is understood that everyone agreed with what Enver said, they agreed without question, and their motto was even: “to be firm with the enemy, loyal to the Party.” My father had his biggest clashes with Hysni Kapo, and at the latter’s request, after some possible contradiction, for the eliminations in the Party ranks, which were agreed upon by all the bureau members.

But my father was a just man, he did not easily accept deceit, and for this reason, after many years of work at the Central Committee, they sent him as Party secretary to Shkodra, and then to Durrës. His last experience would be at the “Zëri i Popullit” newspaper, as editor-in-chief, while precisely because of the clashes with Hysni Kapo, my father ended up as a director in a shoe factory in Tirana until he reached retirement age. And an event that had to do with me had even more influence on my father’s clashes…!

What specifically?

In 1974, when the group of generals was hit, I was at a fair in Greece. A group of Albanians approached me there, people from the State Security, asking me directly; what possible information I had about this event, from my father. However, when the activity ended, a woman (a Greek) a few days later, as a sign of gratitude for the books I suggested and the communication we built during the days of the fair, sends me a letter as a thank you.

This fell into the hands of Hysni Kapo, who accused me of having connections with Greek agencies, and he conveyed this opinion directly to my father. This later became the reason why the clashes between Kapo and Sadik, that is, my father, became continuous until he ended up in a shoe factory.

Compared to others, you can’t say you weren’t privileged, right?

Even in those years, I finished two faculties, and my first job in 1970 was at the Chamber of Commerce Abroad. It was a beautiful and responsible job, for the fact that we were the main link with the foreign gate, that is, with foreign trade, where we had to import and export various goods every day.

For example, Albanian chromes ranked third in the world for the quality and quantity we exported. It was our duty as the Chamber of Commerce to act as an intermediary, to make our Albanian products known to foreigners, starting with food and artisanal ones, like carpets from our artistic enterprises, etc. So, everything was “Made in Albania.”

What goods were imported in large quantities, what did our country need most?

They were mainly tools, machinery, and various electronic equipment needed for work processes in factories and plants.

Is it true that there was a special sector for the leadership’s “Bloc” in the directorate where you worked?

There was the Reception Directorate for the leadership, which was located near the Chamber of Commerce Abroad, and mainly from imports, specially ordered clothing for the bureau members came there. This included high-quality and expensive fabrics, as well as special suits.

Even though there was a specific sector in the Tirana VET (State Enterprise of Clothing) where clothes for the bureau members were sewn, or even though the first ladies of the country had the opportunity to buy things they liked whenever they went on trips abroad, there were still certain goods that came with specific orders for the leadership.

How did you then move to the Propaganda Sector at the Book Enterprise?

After working for several years at the Chamber of Commerce Abroad, I was engaged as a Propaganda inspector at the Book Enterprise, until I reached the post of head of the Propaganda Branch at the Book Enterprise, a place where I worked until the beginning of 1991, as soon as the first days of the fall of the communist regime were felt. It is understood that every publication and book went through a sieve, every sentence and every photo that accompanied the inner pages of the publications. It was a job with great responsibility, to be honest.

What was the function of the sector you led?

The enterprise had the special task of taking all the publications from the two main Publishing Houses; “8 Nëntori” and “Naim Frashëri,” the first one dealt with socio-political, technical-scientific, and translated books, while the second one dealt with the editing of various publications of artistic literature, novels, stories, poems, children’s literature, etc.

We had a transport workshop, in which we took all these publications and sieved them one by one. Afterwards, we prepared leaflets and distributed them everywhere, so that people would know what new publications had been published.

Which publications did you focus on most?

Of course, those that had a stronger political content, especially to check them from the orthographic side, but also the graphic one. Mistakes were intolerable. In fact, if during the time of publication there was any elimination of leaders, his name was erased from the places where he was mentioned, and besides this, the photo, which was montaged by erasing the person in question.

It was very tiring for every sentence to undergo deep editing, because then these publications was distributed to the people, and then our propaganda and work was to convey it to the countries of the East and those of Europe, through the various fairs we organized.

I went to Radio-Tirana twice a week, so it was a propagandistic form to talk about new and most requested books. I have not escaped my primary role that of emphasizing the evaluation of the dictator’s works. Our work was then passed through other filters of the directors of the propaganda sector, who were initially Gani Keçi, and then Estref Bega, and Fisnik Sina.

Being a job of special importance, did you often have visits from the bureau members?

Not from them directly, but from their delegates. Sevo Tarifa, who was responsible for the book sector at the Central Committee, often came to our enterprise; he came to us and took works, especially those of Enver Hoxha, or even other leaders. Also, Agim Popa came, who was in the foreign directorate, and his interest was mainly in the leadership’s books in foreign languages.

You said that the leadership’s works were mainly presented at international fairs. Where was the most targeted?

We organized fairs in the country as well as in Europe. It was our request that the fairs in these states be organized in those places where there were more Albanian and Kosovar emigrants, because the publications in Albanian were larger, while the other publications, in French and English, were more reduced in number, which were translated by well-known names, Jusuf Vrioni and Robert Shvarc.

What was the interest of foreigners in Enver Hoxha’s works?

Absolute! We did not return any book written by Enver Hoxha to Albania. All the publications were sold, and in the end, it turned out that our stand, that is, the one from Albania, was the most successful and with more copies sold than the others.

The interest was extraordinary in Enver Hoxha’s works, and this is understandable because we lived in a communist period and the need to spread the propaganda of the Party of Labor of Albania…! The prices were a little more expensive than the real ones, but this was acceptable. The biggest buyers were foreigners, who asked for the dictator’s works in foreign languages.

How did the propaganda spread in Albania?

I said that, in addition to my role with the radio broadcasts, we in the enterprise had a very well-organized work line regarding the distribution of the leadership’s books, and those of other genres. We had a distribution workshop for the 26 districts of the Republic of Albania, and through trucks, we took our shipments to the heads of the book branches according to the districts.

Of course, we emphasized books of a political nature, Hoxha’s works, but without leaving aside the readers’ interest in artistic books and not only. It was very difficult then to get a certain book; even people who were friends came to us in the enterprise to get a book by Enver, or others.

Today, times have changed a lot, regarding the freedom of the book, right?

I think that every political system has its own flaws and merits. For the time in which I worked, the issue of treating propaganda through books, that with a truly ideological character, was the primary interest of the leadership, which aimed to reach the people, the simple reader through books. And this was not a random thing; it had happened to the entire sister systems of Eastern Europe, wherever the socialist system occupied societies.

Our task was clearly defined; our role was to go with our selective work as it should into the minds and hearts of the simple people. It is understood that the publications were limited in number, the process was slow, but in essence, it was the work that had to be done properly. Today, books are plentiful, you can find any title you want, and there is no way for someone else to get a friend to get a certain volume. / Memorie.al