Memorie.al / We bring to the reader for the first time a fragment from the unpublished drama of Shpëtim Gina, written in the early ’70s. The breakdown of Albanian-Russian friendship, in a unique version, as a human drama. Today, many years after the tragic end of the unrecognized 23-year-old writer. “Everywhere it is said that things are bad. We broke up with friends and someone said that the anger of broken friends is the most terrible!” What happened next? The shadows came, surveillance, the destruction of intimacy, the hitting of strong loves, the young became old and the old became children. The time of blockades came. Isolation greater than the isolation that the entry into the communist red bloc had put Albania in.

In 1959, Khrushchev laid the first brick in the foundations of the Palace of Culture in Tirana, which would be built according to the model of Russian architecture. Two years later, in 1961, the Khrushchev-Hoxha couple broke up forever. The drama “House No. 1961” by Shpëtim Gina is based on this year.

The character who talks about the anger of friends is an architect. And who better than an architect, can talk about the structure of a regime that had put the country on a blind path: “There is no other way. There are wolves and imperialists there. They will take it from us. Let’s drag it to communism. There we will lay it on a board!”

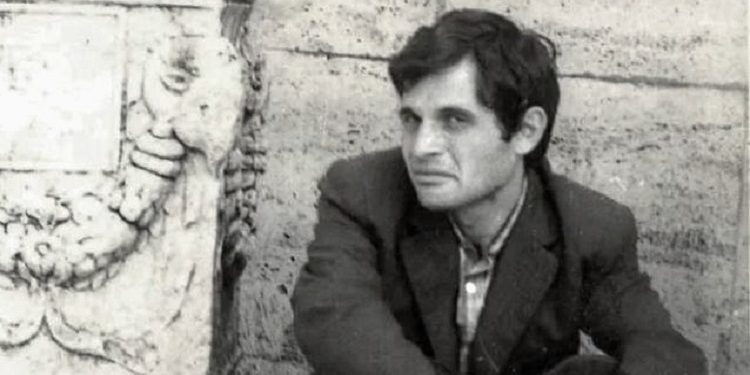

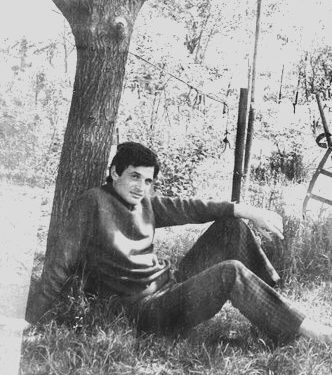

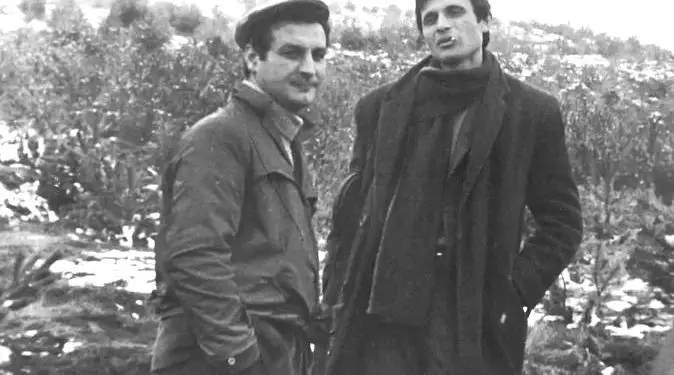

Today, many years after the tragic end of the playwright Shpëtim Gina, we are publishing for the first time a fragment from the drama in question. The author of a total of 7 dramas, essentially unknown to the reader, wrote “House No. 1961”, at a time when he wrote all the others, in the years 1970-1974. On August 15, 1974, he was found drowned in the Droja River near Mamurras, in mysterious circumstances, while he was in a military exercise.

This drama, which Gina’s sisters knew existed, fell into the hands of the director Viktor Gjika, to whom the playwright had given it to read. When a drama by Gina, “The Weight of Peace” (“The Accusation” – is the original title), was staged for the first time at the National Theater, Gjika handed over the original manuscript, which he had kept for over 30 years.

One of Gina’s close collaborators, the director Pali Kuke, says that it is so significant that; “this boy at a time when the state that had set up the barbed wire did not allow the circulation of modernists, and Shpëtim did not know the modernists, he wrote like a modernist”.

Gina adored Dostoevsky, Hemingway, read poetry by Éluard, Aragon, Yevtushenko, but it is late to say that he was influenced by these and others. The fact that he cultivated, after poetry, only drama, is an ambition to search in an untrodden path, a feature that only talents prove.

Gina is not a cultivated connoisseur of dramatic technique, but he builds his own architecture whose strength lies in other elements, in dense and strong psychological dialogues, in the unraveling of a monotonous way of theatrical narration, in sudden leaps, both in small scenes of reality, and in the big ones, of the world of thought.

Even in “House No. 1961” which his sister, Mira Gina, offered us, we find a drama not as well organized as “The Accusation”, which we have seen and read, or as “The Enemies”, which was to be staged by the director Mihal Luarasi, but was stopped just before the premiere. This drama is not as strong as “The Accusation”, but just like “The Accusation”, it gives us a modern tableau, where the importance is not taken by the matter, the object, but the undoing of the matter, of the object to get to its essence, where an indirect human relationship is conceived, but the analogy of a spiritual, dark, futile, frightening reality.

We are dealing with a drama about the diabolization of power, about its undecipherable architecture from the Minotaur. All this could not fail to make Gina’s work unacceptable, which nevertheless passed underhand in the circles of the most famous artists of the time, in Tirana in the ’70s.

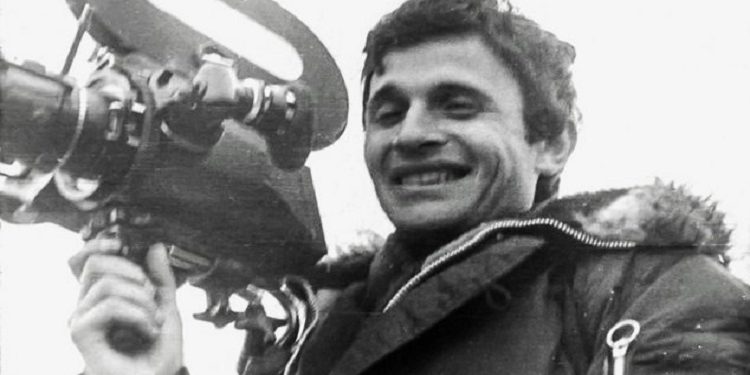

Gina collaborated as a screenwriter for several documentaries by Pali Kuke and Mevlan Shanaj. Pali Kuke recalls the documentary “Berat”, made in 1972. “Berat was interrupted, and for this, they took us to the IVth Plenum. The whole aroma of Berat, how it was filmed, how it was spoken, was different and as a result pushed the apparatchiks, whom we thought could not read the metaphor or ellipsis in that film, to stop it. In fact, they read these in “Berat”.

Pali Kuke is one of those who has read Gina’s dramas and thinks that at first glance they look dark, but they are not dark at all as one might think. “In short, they are special. Shpëtim was for symbolism. You are dealing with a very special figure in this whole sky of Albanian artists”.

Pali Kuke accepted that he could make a documentary about a completely unknown character of letters, referring to his sister Adelina Gina’s memoir book, “Where did you take Shpëtim?” “It would be a very modern film, which would start with the interruption, just as the life of Shpëtim Gina and his unapproved work could not be conceived otherwise.”

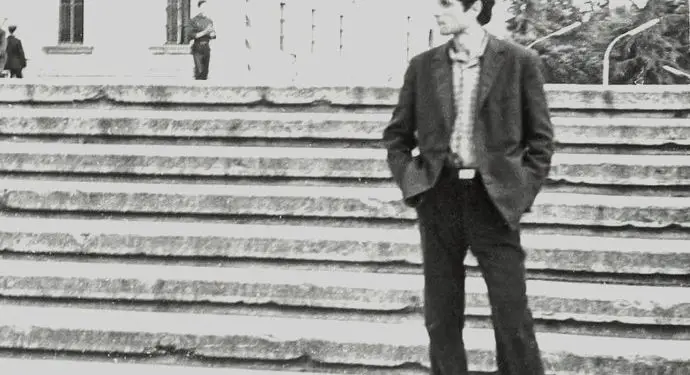

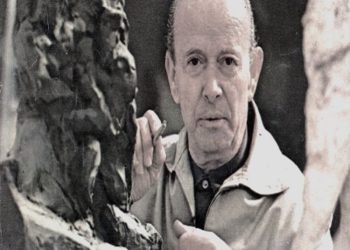

VIKTOR GJIKA “WANTED TO REACH THE GREAT TRUTH”

The director Viktor Gjika, one of Shpëtim Gina’s friends, who kept the manuscript of the drama “House No. 1961” for 30 years, comments on some of the playwright’s works.

Mr. Gjika, how do you remember Shpëtim Gina?

Special, very special?

What made him special?

His thoughts, the dramas he wrote. I am not saying that his dramas were perfect, but the research within them was very interesting, especially for the time.

How did you get the drama “House No. 1961” which was finally handed over to the family?

Shpëtim gave it to me with his own hand to read. He needed to process it. But what happened happened. I experienced the news of his death as a total tragedy.

What do you think of his dramas?

Shpëtim’s dramas seem dark, but they have an underground language. Such is “House No. 1961”. But what I liked the most is the drama “The Accusation”. The courage of such a young boy makes an impression on you. For me, he remained a talent who unfortunately did not fully achieve what he wanted, he could not.

Did he express among you those thoughts that appear in his dramas and that are contrary to the whole spirit of a dictatorial regime?

This cannot be fully said. He had it more as a demand on art and not on the nonsense of our daily life. Finally, I say that; even where Shpëtim Gina reached with his art, for me it is a lot.

What strikes you in what he created is the allegory, because this boy wanted to reach the great truth. It is not a question here of either overestimating him or underestimating him, by not publishing him. The work of Shpëtim Gina needs to be edited by someone who loves this author.

EXCLUSIVE

“House No. 1961”

The dialogue between the two central characters of the drama, the architect Madu, whom the government has entrusted with the task of building a palace that, would bring him a misfortune, and the Sculptor, a foreign restorer, who had come to Albania at the time of our country’s friendship with the Communist Bloc. The references to the dictator’s figure are clear. Here is the dialogue, about the state, politics and art.

Madu – Why did you come to Albania?

Sculptor – To restore that sculpture, which you would later have as your god.

Madu – We have no gods.

Sculptor – Every people has its spiritual foundation. You would have that.

Madu – Where is the statue?

Sculptor – It’s getting drunk.

Madu – It’s not human.

Sculptor – The artist always brings his work to life by comparing it to people. This is the comfort of art. In this way we are not alone, although outside of everything that has nothing to do with beauty, art.

Madu – Do you like politics?

Sculptor – The cocktail has seemed futile to me. It is mixed and it is understood that there is a lack of sincerity…!

Madu – Do you know how much the blockade weighs?

Sculptor – Your questions are strange. And you are quite young!

Madu – Are you leaving…?!

Sculptor – (Interrupts him) I haven’t decided yet.

Madu – It’s not for you to decide. (After a while) You took everything and you are leaving. The blockade is stretched all around.

Sculptor – This is open politics. I would ask you not to continue the conversation in this way. A true artist’s taste can be spoiled in such conversations.

Madu – Does what we are talking about have to do with politics?

Sculptor – I think so.

Madu – Then you know politics well.

Sculptor – I know the politics of statues. It’s very nice to deal with the diplomacy of statues. They have traveled with caravans in the middle Ages and have made long journeys through lost lands. That drunken statue has a terrible muscle tension, they gave it to me to restore. As if he continues to ride on a flying horse, among enemies who are chasing him. This is how I know politics and this is what distances me the most.

Madu – Even an ancient statue has something from today’s time.

Sculptor – Of course! People are like states and in their constructive structure, they have never changed. States curse each other, rape Virgin Islands, do a lot of mischief and the next day they laugh at each other. The statues have not changed only because art has always been outside of politics. What do we need politics for?

Madu – What about the palace?

Sculptor – We need it. It must be a sanctuary for people who do not mix with the general weakness called politics. Politics is the state of intoxication of nations. In such a state, at most it can reproduce itself but nothing outside of it. Thus the artist must move away from it…!

Madu – The palace that would serve people who stay away from politics, in its construction, is subject to it. Why did you leave, who abandoned it? It must be raised. The building does not belong to any diplomacy. Can you organize a crusade of artists (he mocks) to protect this “unfortunate” building that must be subject to politics? Its fate is terrible. Imagine if you yourself were made of bricks and were subjected to it in this way. You would be a building but in cubic form but with cubic form of…!

Sculptor – It is a victim. But I can say that no one would help me. I wouldn’t even allow it. He would reach out and disappear into my fate.

Madu – Leave!

Sculptor – This is also politics. It seems that you reached out to that building and it gave you its fate. To be a victim is an abstract pleasure for a true artist.

Madu – And to be a runaway, is a betrayal that politics condemns, by calling you an enemy. This brings war.

Sculptor– Ah war! / Memorie.al