From Yamamoto KAZUHIKO

Memorie.al / The Gheg tribes in the northern highlands of Albania have a customary code known as the Kanun. In a tribal society like that of Northern Albania, where the judicial system does not function well, an act of revenge carried out by the injured party is the ultimate sanction to punish a perpetrator or an offending party, a necessary step to restore and maintain social order in human society. In Northern Albania, an act of revenge against an offender who commits an ugly act, which the Kanun considers an unethical action, is judged as an act of justice.

The question of how ethics and social order arise and develop in a society without state power is one of the enigmas that human beings have long tried to solve. It has been rightly assumed that before state power appeared in human society, human beings lived in a society where this power was absent. Thomas Hobbes was the first to show that a social contract constituted the beginning of social order in a society without state power.

Rousseau, Nietzsche, and Girard proposed theories on the origin of social order, supported by Hobbes’s social contract theory. However, all these theories must have failed to discover that a society without state power has its own personal ethics, which have developed spontaneously as a result of a pagan culture. The tribal society of Northern Albania, where the Kanun exercises normative power in place of state power, has its own ethics and social order.

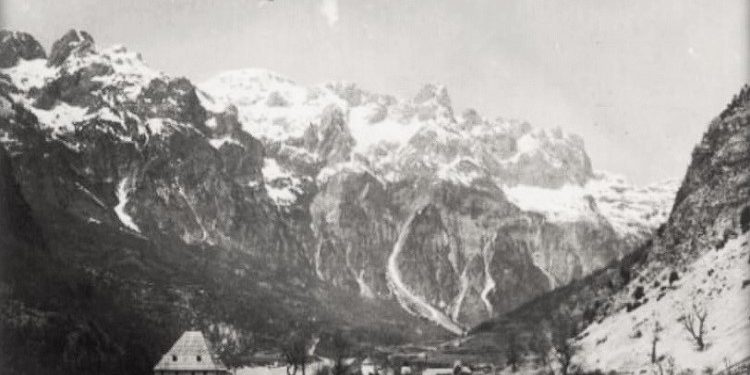

In this paper, I will clarify the ethical concepts of the Kanun and propose a new theory on the origin of ethics and social order in human society, using the ethical structure of the Kanun. The northern part of Albania consists 1of a rugged mountainous terrain with deep gorges, with the exception of a narrow strip along the coast of the Adriatic Sea. The population of this area, which speaks the Gheg dialect of the Albanian language, has preserved tribal structures based on the Family, Brotherhood, and Clan until the Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha destroyed it after the Second World War.

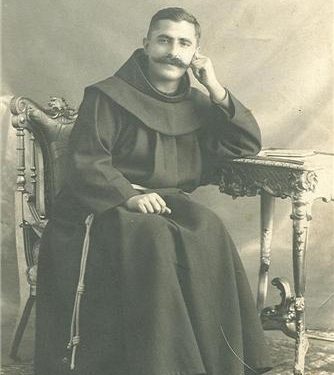

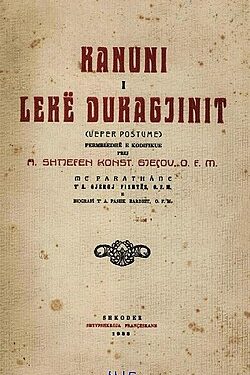

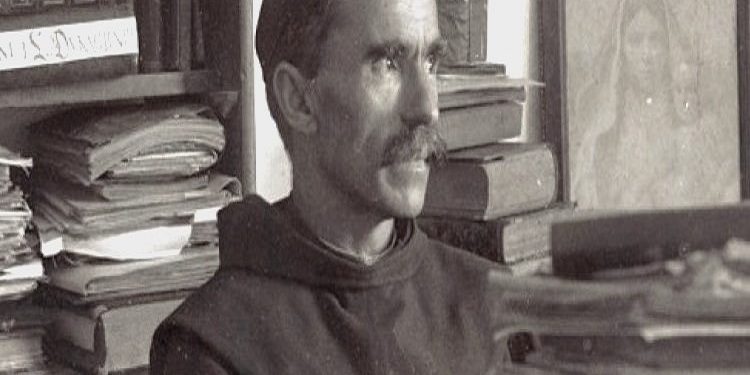

The highlands of Northern Albania have been subject to the customary tribal code called the Kanun since the middle Ages. The Kanun was transmitted orally among the Albanian tribes until the Franciscan friar Shtjefën Gjeçovi finally managed to compile the code, which was published after his death in 1933, under the title Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit (Lopasic 1992: 89-105).

Ethical Concepts of the Kanun

The Kanun, collected and codified by Shtjefën Gjeçovi, consists of 1263 articles. Since article 1181 is similar to article 1081, we are actually dealing with 1262 articles (GJEÇOV 1989 [1933]: 198, 208). The most distinctive feature of the Kanun is that it allows men to take revenge, an action that functions as a sanction against the violation of the rights of others. If an act of revenge carried out by the offended party is not supported by ethical concepts, it results in endless wrongdoing and violence.

The fact that for several centuries the Kanun has functioned as a customary code in Northern Albania and Kosovo, which created opportunities for the people to maintain social order by resolving conflicts within the community, shows that the population in this area considers the act of revenge defined in the Kanun as an ethical action. Clearly, the concept of revenge is the cornerstone that can potentially develop the ethical structure of the Kanun.

Since the Kanun clearly defines that spilled blood must be paid for, it is understood that revenge is inextricably linked to the concept of “Blood.” Searching for the causes of such vengeful violence, which consequently results in bloodshed, provides us with the key to understanding the concepts that build the ethical structure of the Kanun. It is easy to discover that the four concepts, “Oath” (Betimi-Beja), “Pledge” (Besa) (besa is an oath for a truce), “Honor” (Nderi), and “Guest” (Miku), are associated with “Revenge” (Hakmarrja).

For example, when a man is insulted, he has every right to restore his honor by killing the offender. When a man or a guest is killed, the spilled blood must be paid for. In this way, all four concepts, “Oath,” “Pledge,” “Honor,” and “Guest,” will converge on the concept of “blood,” through a vengeful act of violence. What is the ethical background that convinces a man to kill an offender when he is shamed? “Why is a man obligated to seek revenge when his guest is killed?”

When we try to understand the ethical structure of the Kanun using the six concepts: “Oath,” “Pledge,” “Blood,” “Honor,” “Guest,” and “Revenge,” we fail to do so because we lack a crucial link between these concepts. Then I discovered that the marebito (guest-deity) theory, proposed by Shinobu Orikuchi, a Japanese folklorist and writer, was a key to solving this dilemma. According to him, the deity appears disguised as a guest during religious rituals of ancient Japan.

When the God-Deity, disguised as an old man, visits a village twice a year to bless the people, a host must treat the guest-deity with special hospitality (ORIKUCHI 1972 [1954]: 3-62). In return for the hospitality, the guest-deity gives a blessing to the host, a blessing that ensures the happiness and health of the host family. In the ritual of welcoming a guest-deity, offering food to the latter is a moment of critical importance. There are no rituals for a visiting guest-deity without food, which is eaten in a proportional and shared manner.

It seems that Albanians have a concept of the “Guest” and a tradition of hospitality similar to that of the ancient Japanese. The Kanun says: “The Albanian’s house belongs to God and to the guest” (Article 602). The guest must be honored with bread, salt, and heart (Article 608). The Albanian writer Ismail Kadare writes: “The guest inside someone’s gate (house), for an Albanian, is more sacred than anything else.” “The guest, in the life of an Albanian, represents the highest ethical category, more important than blood ties.”

The comparison of culture and tradition between Albanians and ancient Japanese leads us to the concept of “Food” (Ushqimi), which is an essential element for understanding the Kanun. In this way, we discovered seven ethical concepts in the Kanun: “Oath,” “Pledge,” “Blood,” “Honor,” “Guest” (guest-deity), “Food,” and “Revenge.”

“Oath” – “Beja”:

“An oath is a faithful act by which a person, wanting to clear himself from a shameful accusation, must touch a sign of faith with his hand, invoking the name of God as a witness to the truth” (Article 529). A person accused of theft or murder is allowed to clear himself by taking an oath that he is innocent in the name of God. If he makes a false oath, either intentionally or unintentionally, he is a dishonest man who must be punished with a heavy fine or by expulsion from the community. The one who makes a false oath may lose his life or that of his kinship group, as it is assumed that God’s wrath will fall upon him.

Besa (Pledge): “Besa is a period of freedom and security, which the family of the victim gives to the murderer and his family, temporarily suspending the taking of blood until the end of the specified period” (Article 854). When a person seeking revenge kills his enemy, he is given a pledge of 24 hours, during which he must await the funeral of the killed person, and then a pledge of 30 days. During this period, he is under the protection of the pledge, and his enemies are forbidden to kill him. Besa is a type of oath taken by the injured party, bringing a temporary cessation of bloodshed.

Gjaku (Blood): “For the Highlander Albanian, the chain of blood relations is endless” (Article 695). “If someone insults me and I kill him, I take the blood upon myself” (Article 910). “Blood is never unavenged” (Article 917). “After they mix the blood of one another and shake it well, drinking each other’s blood, they become like new brothers, as if born from the same mother and father” (Article 990). Blood in the Kanun is a metaphor for human life, kinship, and blood feud. The blood of an offender, or of a member of the offending tribal group, is the only thing that allows the injured party to neutralize the dishonor or spilled blood.

Nderi (Honor): “An offense against honor is not paid with property, but through the shedding of blood or through a public act of forgiveness” (Article 598). “A man who is dishonored, according to the Kanun, is considered dead” (Article 600). “A man is dishonored: a) if someone calls him a liar in front of a group of people; b) if someone spits on, threatens, pushes, or hits him; c) if someone betrays his promise for mediation or breaks his word; d) if his wife is disgraced or if she goes with someone else” (Article 601). Thus, when the offended party cannot forgive an offender, they will take revenge for the dishonor suffered in the community.

Miku (Guest): “Every guest should be given food as the host eats himself” (Article 611). “The guest is placed in the place of honor at the table, and consequently is under the protection of the house” (Article 653). “A guest is an honored man who must be treated with due hospitality as if he were a divine being. If the guest, under the protection of the host, is killed, his blood must be taken at all costs.”

Ushqimi-Buka (Food-Bread): “The traveler, like the messenger, travels for payment and with his own food; therefore he is not under anyone’s protection” (Article 489). “A rifle or bread given with prior knowledge that it will cause death brings blood upon the one who gives it” (Article 839). “The food of blood happens when the mediators of a blood feud, along with some relatives, friends, and associates of the blood owner, go to the murderer’s house to settle the blood feud and eat a meal to observe this reconciliation” (Article 982). “If the members of the elders eat bread with the accused, they are considered to have taken the pledge” (Article 1068). The people of Northern Albania develop and strengthen their relationships with each other by eating food together. If food were not eaten (or if food were not eaten together), rituals such as giving a pledge and reconciling a blood feud, according to the Kanun, would not be considered fulfilled.

Hakmarrja (Revenge/Blood Feud): “The injured person has the door open for his honor: he lays no pledge, takes no elders, seeks no trial; takes no fine. The strong man collects the fines himself” (Article 599). “According to the Kanun: an offense against a father, a brother, and even against a cousin without an heir, can be forgiven, but an offense against a guest is not forgiven” (Article 649). When unethical acts are committed in the community, the injured party takes revenge to restore balance and an equal position in this community.

(Translated and annotated by Prof. Dr. Romeo GURAKUQI).

Who is Kazuhiko Yamamoto?

Kazuhiko Yamamoto currently works as a professor at the Institute of Health Sciences at Kyoto University, with an M.D. and Ph.D. degree. His areas of specialization are Internal Medicine, Health Sciences, Psychological Anthropology, and Cultural Anthropology on Ethics. Among his most important studies in the field of Ethics are: The Ethical Structure of the Kanun, Illyria, The Ethical Structure of Homeric Society, and The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini similar to the Japanese code “Mitochin,” The Origin of Morality and Social Order in a Society without State Power.

The study that we are presenting in this issue and then in the following issues, aims to introduce the ethics of the Kanun in its origin, its brilliance, and its decline. The thoughts and theses are only of the author and the translator, and we have respected that by not making any comments. / Memorie.al