From Nafi Çegrani

Part Three

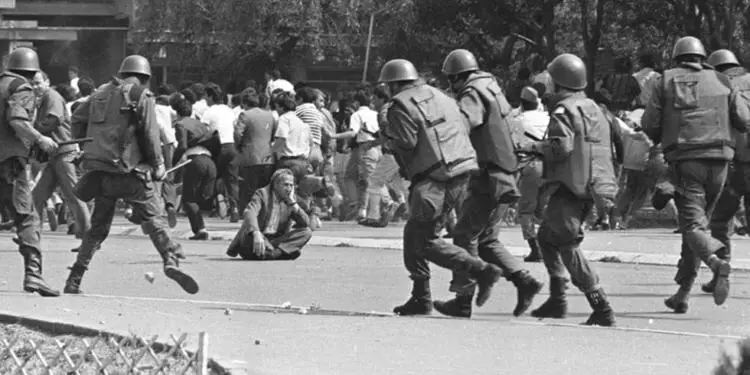

THE PHENOMENON OF YUGOSLAV SPYING

Memorie.al / Espionage, known since ancient times as the “invisible eye of power,” always took on a tragic and bloody hue in the Balkans. In this region where empires have clashed like waves on rocks, secrecy and betrayal became everyday currency. For Albanians, this phenomenon was not merely a technique for rulers to control the populace, but a wound that became ingrained in the collective psychology and historical consciousness. At its core, espionage is not just the gathering of information—it is a refined violence against the human mind, an intrusion into the most intimate zones of freedom. It mixes fear with suspicion, causing a person to lose their inner peace and society to be torn apart by mistrust. In this sense, espionage is a second act of slavery: the first is physical chains; the second is the imprisonment of consciousness.

Continued from the previous issue

1967–1970 – Double Control and Sacrifice

During this period, tension reached its peak. The UDB intensified operations to control the activities of students in the diaspora and within Yugoslavia, while the Albanian State Security (Sigurimi i Shtetit) strengthened surveillance to prevent foreign influence on young individuals. Students were forced to use coded letters, secret meetings, and double-meaning messages.

Some of the most dramatic actions included:

- Warning friends about UDB operations, risking their own careers and lives.

- Withholding certain information from the Albanian Sigurimi to prevent baseless arrests, without betraying the trust of the community.

- Refusing orders that would lead to arrests or persecution, a decision that often cost those scholarships, separation from family, or symbolic punishment.

Personal and Moral Consequences

By the end of the ’60s, the consequences of their actions became evident: some lost the opportunity to study abroad; some were isolated from the academic community; others lived with the constant fear that any move could expose them to both networks. Those who continued to act with conscience often experienced constant psychological tension but maintained their integrity and morals.

Philosophical and Sociological Reflection

The history of this group shows that intelligence networks are not just mechanisms of power, but also a test of human nature: the tension between fear and conscience, survival and loyalty to values. Sociologically, this journey illustrates the fragmentation of a community and the power of fear to affect social relationships. Philosophically, it shows that even under the greatest pressure of espionage, there is room for sacrifice, morality, and inner resistance.

It was a cold winter evening in 1967 when an unexpected notice reached the hands of the group of Albanian students in Belgrade. The UDB had planned an operation to arrest an Albanian professor who was suspected of “foreign influence” and secret activities that could favor Albanian political emigration. The professor was known for his honest stance and his support for Albanian students.

The group met in secret, feeling the tension growing with every minute. One of the young men, who had direct access to UDB reports, realized that the professor was in immediate danger. The moral dilemma became unbearable: if they intervened, they risked their own careers and lives; if they didn’t act, an innocent life would be broken.

After long discussions and a heavy silence, a decision was made: they would use the information they had to change the professor’s itinerary and to warn some close collaborators, without exposing their identity. The messages were sent in coded form, and meetings were secretly organized in different apartments.

When the UDB operation was carried out, the group followed the movements of the operatives from a distance. The tension was indescribable: every mistake could be the difference between life and arrest, between freedom and prison. The professor managed to avoid capture, thanks to the students’ silent intervention.

At that critical moment, conscience and morality became their strongest weapons. They realized that every decision made in the darkness, every secret act of sacrifice, was a small victory for freedom over the absolute control of power. But the personal consequences were not absent: some students lost scholarships; some were isolated from friends and professors, while others lived with the double burden of secrecy and psychological tension.

This dramatic scene clearly shows the double game: a sophisticated interaction between the Yugoslav and Albanian networks, where the Albanian individual often had to find a path of morality and freedom within the labyrinth of surveillance. It illustrates that espionage is not just a mechanism of power, but also a test of human nature, a battle for integrity, conscience, and sacrifice in the darkness of absolute domination.

DOUBLE AGENTS AND ALBANIAN EMIGRATION

The phenomenon of double agents was one of the most complicated dimensions of classical espionage in the Balkans and the Eastern Bloc. In Yugoslavia, the UDB created this category of individuals to infiltrate Albanian communities, monitor political and cultural activities, and build a control network that extended beyond the borders. In Albania, the State Security used similar methods, trying to identify and manipulate any suspicious contact with the diaspora or with foreign services.

Double agents became sophisticated instruments to manage the tension between the two powers. They reported simultaneously to the service that recruited them and to their community or other services, maintaining a delicate balance between survival and moral conscience. This category of individuals often lived with a permanent psychological burden, as any mistake could lead to arrests, persecution, or total isolation.

In relation to Albanian emigration to the West, especially the USA, Germany, France, and Switzerland, double agents were used to infiltrate emigrant organizations. The UDB and the Albanian State Security engaged individuals who had family or academic ties to the emigration to report on political activities, diaspora meetings, and funding that supported national initiatives. Many of them were presented as “trusted collaborators” of the community, but in reality, they served two services simultaneously.

Concrete examples include Albanian students in American universities in the ’60s and ’70s, who were initially recruited to oversee student organizations and patriotic activities, but some of them developed secret contacts with representatives of Albanian communities, helping to maintain the integrity of organizations and save individuals at risk from secret services. In Germany and France, some members of emigrant organizations were discovered as double agents, creating division and mistrust within the diaspora’s ranks.

The phenomenon of double agents explains the tension between loyalty to the community and duty to the secret service. Individuals faced permanent dilemmas: to act to protect their compatriots and families, or to fulfill orders that often brought tragic consequences for others.

By understanding that this phenomenon contributed to the fragmentation of the Albanian diaspora, things become clearer. Mistrust, isolation, and secret control influenced how emigrant communities organized and cooperated. Many old ties were destroyed, while trust became a luxury.

Double agents are a symbol of the tension between inner freedom and the absolute control of power. They show that a person often has to balance between two worlds: a visible world where they live in security and a secret world of conscience, where moral decisions determine not only their own life but also the fate of the community.

This phenomenon shows that even far from home and in the diaspora, espionage is not just an instrument of power, but a mirror of the complexity of the Albanian soul amidst external pressure, fear, and the need to preserve identity and dignity.

THE DIASPORA AND THE UDB

In the ’60s and ’70s, some Albanian students and professionals who emigrated to the USA, Germany, and France were faced with offers for collaboration from the Yugoslav and Albanian secret services. A part of them, feeling isolated and lonely far from their homeland, agreed to serve as informants, often under the pretext of helping their country and community.

A typical case was that of an Albanian student at Boston University in the USA. He was initially recruited by the UDB to report on the activities of Albanian students and their ties to patriotic organizations. But very quickly, he also became involved in contacts with the Albanian State Security, becoming a double agent.

In his actions, he avoided the arrest of some compatriots by transmitting controlled information and maintaining the secrecy of organizations. The moral dilemma was constant: every report could cause punishment; every silence could support a risk for others.

In Germany, a group of Albanian professionals was recruited by the UDB to monitor the activities of emigrant organizations in Frankfurt and Munich. They reported on meetings, funding, and diplomatic contacts, but some of them developed secret ties with the Albanian community, saving individuals from secret service plots.

A member of the group, facing pressure, decided to sacrifice personal relationships and professional opportunities to maintain the integrity of the organization and the lives of his compatriots.

In France, some Albanian intellectuals were recruited to report on the cultural and political activities of the diaspora in Paris and Lyon. They were forced to use coded letters, secret meetings, and double-meaning messages to avoid the suspicion of authorities and to maintain the trust of the community.

Their sacrifices included social isolation, loss of professional opportunities, and a permanent psychological burden, but for many, maintaining dignity and moral integrity was a greater victory than any career or material gain.

The impact on the emigrant community was twofold: while secret services created tension and mistrust within the diaspora, the secret intervention of some double agents saved many individuals and preserved the functioning of patriotic organizations. They learned to act with caution, keep secrets, and secretly support their compatriots, creating a unique morality of survival and conscience.

Psychologically, this phenomenon showed the tension between loyalty to the community and pressure from the secret services. Sociologically, it explained the fragmentation of the diaspora and the creation of an atmosphere of constant suspicion. Philosophically, their history illustrated the permanent battle between inner freedom and external control, and the power of human conscience that can be preserved even under the greatest pressure.

These specific cases show that Albanian emigration to the USA and Europe was not just a path to a better life, but also a ground where a sophisticated moral and political battle took place, where every decision had an impact on the lives and fate of compatriots, leaving deep marks on the history of the Albanian diaspora.

CODES, CIPHERS, AND SECRECY – OPERATIONS OF COMMUNIST AGENCIES IN THE WEST

During the communist period, the intelligence agencies of Yugoslavia (UDB, OZNA) and Albania (State Security) used a sophisticated language of secrecy, based on codes, ciphers, and symbols that enabled the management of intelligence networks and the control of information, often in a perfidious and invisible way.

The main methods of coding included:

- Numbers and symbols – every agent, report, or document had a unique code that was not directly linked to the individual’s name or activity. For example, Albanian students who reported on patriotic activities in Belgrade or Frankfurt were identified with secret numbers and coded initials.

- Hidden signs in letters and documents – coded letters with simple or complex symbolism were used to transmit important information, without using direct words that could be discovered by others.

- Coded verbal messages – during secret meetings in apartments or cafes, agents used seemingly every day phrases that carried a secret meaning to indicate activities or to warn of dangers.

In the Albanian diaspora in Belgium, the USA, Germany, Switzerland, etc., these methods were used to infiltrate emigrant organizations and oversee patriotic and cultural activities. Double agents and secret informants used these codes to report on community meetings, organizational funding, diplomatic ties, and discussions of anti-communist activities.

Concrete examples include:

- Albanian students at Boston University who sent coded reports about the meetings of Albanian student associations, using numbers and initials that only the UDB or Sigurimi could understand.

- Members of emigrant organizations in Frankfurt and Paris who used signs and secret words to warn each other about potential secret service operations.

- Informants who used coded letters and ciphers to transmit news about diaspora meetings in Switzerland, without being discovered by community members.

The role of these codes and ciphers was strategic: they allowed the agencies to act in a perfidious and secret manner, maintaining control over the networks and isolating the emigrant community. But for Albanian individuals who used the information with conscience, they were also a tool to save the lives of compatriots and protect patriotic organizations from repression.

Nevertheless, it requires deep professional preparation to understand things from this field. However, the use of codes and ciphers created a constant tension, because any mistake could lead to arrest, deportation, or punishment. Sociologically, this method influenced how the emigrant community organized and cooperated, causing mistrust, fear, and internal fragmentation.

Philosophically, the code and cipher symbolized the secret game between power and freedom, a battle for integrity and conscience, even far from home. This phenomenon clearly shows that espionage had no geographical boundaries and that, beyond the borders, the Albanian diaspora was a sophisticated ground where political interest, fear, and human morality interacted dramatically.

In the ’60s and ’70s, some Albanian individuals in the USA and Europe faced a dangerous reality, where any contact with the patriotic community could turn into a risk to their life or freedom. They used codes and ciphers to transmit secret information and to maintain the functioning of organizations, often risking their careers and personal lives.

A well-known case is that of the Albanian student in Boston, who worked as a double agent. He used ciphers to send reports on the activities of student organizations, while at the same time warning about dangerous meetings that could lead to the arrest of colleagues. A meeting organized to raise funds for students persecuted by communist regimes was canceled, only thanks to a coded message that the student managed to send without being discovered.

In Germany, a group of Albanian professionals used a simple system of numbers and initials to identify at-risk individuals and to coordinate aid without being discovered by the UDB. A dramatic case was when an Albanian professor, who was targeted by the UDB for arrest and deportation, was warned via a coded letter. The professor managed to avoid capture, while the Albanian agents within the Yugoslav network took great risks to save his life.

In Switzerland, an Albanian intellectual used ciphers and secret symbols in his messages to warn the diaspora about the movements of secret services. A meeting organized to discuss diaspora strategies for helping the persecuted in Albania was saved thanks to the use of these codes. He took a double risk: any mistake could expose his identity and community members, but he decided to act to protect lives and organizations.

The impact on the emigrant community was great. Thanks to these individuals, many Albanian organizations in the USA, France, Germany, and Belgium managed to survive, maintain their function, and continue their patriotic activity, even under the constant pressure of secret services. The individuals who used codes and ciphers became secret heroes, showing that even within the darkness of espionage; there is an opportunity for moral integrity and personal sacrifice.

It was the spring of 1969, I had just started my work as an official of the Republican SDB in Skopje, in the sector for tracking foreign diplomats and military attachés, etc., when I received information from the analytical office that at that time in the city of Frankfurt, the UDB and the Albanian State Security were conducting a coordinated operation against the Albanian emigrant community.

The objective was a group of intellectuals and students who were organizing cultural and political activities to support their persecuted compatriots in Albania and Kosovo. The secret services had shared information and had planned to arrest some of the key figures, creating tension and panic within the ranks of the diaspora. Even about some secret operative actions and combinations that had been undertaken by the Albanian agency from the embassy in Vienna, headed by the diplomat Simeon…! / Memorie.al