By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part One

Memorie.al / I were born on 23.12.1951, in a black month of a time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the brutish investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the cruel prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, mutilated me at the Branch of Internal Affairs in Shkodër; they split my head, blinded one of my eyes, deafened one of my ears, after they broke several of my ribs, half of my molars, and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the pathetic Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After my sentence was halved because I was still a minor, a sixteen-year-old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the Reps political camp, and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the Revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we claim to have. But on October 23, 2013, the Director General of the “Renaissance” government sent order No. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for the termination of a police employee’s duty. Thus, Divine Providence became entangled with the neo-communist “Renaissance” Providence, and precisely on the 23rd, they replaced me, with nothing less than the former operative of the Burrel Prison State Security. What could be more telling than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

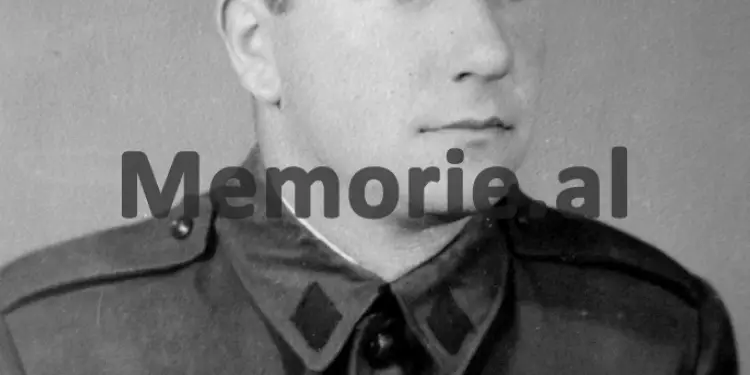

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

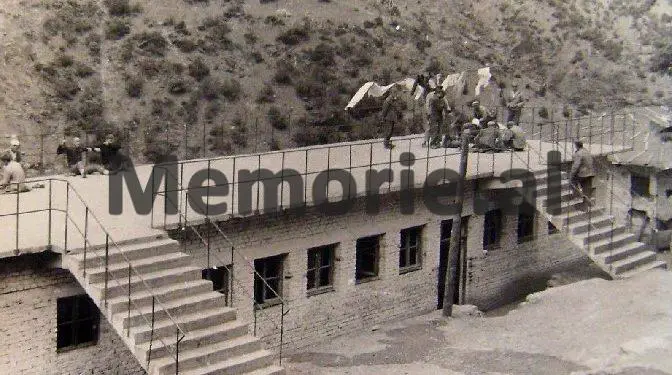

REPSI

(The Forced Labor Camp)

Memoir

That morning, Luigji was the first to get up. As he did every day, he greeted us with a, “How you fellas feelin’?” then started to stretch. He stood up, and his bulky body blocked what little light came in from the narrow embrasure above our heads.

“Please, Luigj, don’t block the light!” I pleaded.

“I swear to God, I gotta stretch a little, ’cause I’m all froze up!”

“Yeah, but come closer to the door and leave us the light!” I begged again.

“Come on, man, tonight’s the last night here!” he bounced up and down like gymnasts warming up before they leap over the vaulting horse. “Tomorrow morning, who knows where dawn’s gonna find us!” he added, twisting his joints, which cracked like a goat’s knees.

He did a few more jumps, then squatted down and began rubbing his large, bear-paw-like hands.

“Brr-rr-rr, it’s so cold, men!”

It was indeed cold. All night we had been pushing and nudging each other, not only because the cell was so small but mostly because we couldn’t feel any warmth.

“So, Bixh, got any news?” I asked deliberately, just to pass those minutes until it was our turn.

“I swear to the Great One, today I had some real beautiful dreams!” the lanky guy turned to me.

“Enough, Bixh, you’re making us sick with your dreams!” Ladi cut him off.

“But listen to me, man, this one dream is gonna come true! You’ll see!” Luigji argued back.

But Ladi didn’t let him continue:

“Hey, do you know any other trick to get to the bathroom a little sooner? My bladder’s killing me!”

We had been together for about two weeks. The day after the trial, they put Ladi and me together in cell fourteen, which was a little more spacious than the one I had shared with Matish. After a few days, they brought Luigji. So, from two, we became three.

They turned us into a clan again. The custom that, as soon as a trial was over, the condemned would be gathered in shared cells, in groups of three or four, while waiting to be sent to the new prison in Tirana or directly to the labor camps, had been passed down for a long time.

As Matish, a repeat prisoner had told me, the Shkodër prison used to have some pretty large sheds where they crammed dozens of political and common prisoners together, who happened to be held there for long periods.

As the years went by, the number of detainees increased several-fold, and as a result, the need for cells also grew. But by then, experience had also taught them to separate the political prisoners from the common ones. The goal was to keep the latter from being politically “infected,” which had pushed the authorities to reconstruct the prison.

Thus, they broke up the large rooms into several parts and adapted them into mini-cells, one meter and twenty centimeters by two-forty. Ultimately, the number of cells increased, but the space inside them decreased. They crammed us into one of these holes. Three people in a space of two point eight square meters. We could barely get through the days and nights, impatiently waiting for the moment we would be transferred elsewhere.

The transport procedures were delayed, because it didn’t just depend on the wishes of the local leaders, who were ready to get rid of us an hour sooner, but on some major factors, such as delays in the final decision from the higher court, the number of political or common prisoners in a given Branch, (add to this the need for labor in a given work site), etc., and the anxiety would last endlessly.

They wouldn’t start the prison-van for just one or two people. So, we continued to “wait indefinitely” and listen to the symphony of empty guts in cell fourteen. The cell where they placed us for the moment was a little more spacious than the five or six cells I had “traveled” through until then.

Because the embrasure opened toward the inner courtyard, there was less noise, but it was more exposed to air currents because it faced north; it was colder. Its position on the left side of the corridor entrance had the advantage of quietness and the disadvantage of a long wait time for activities.

Usually, when they took us out for personal needs, to the bathroom, and for fresh air in the open areas outside, they would start from cell number one and continue in numerical order. By the time it was our turn, more than an hour had passed. Since this ritual took place twice a day, we knew exactly when we should be ready, so while waiting for our turn, we would crowd behind the door. We waited impatiently for them to open it.

We each had a half-liter urine canteen, but the endless winter night, which lasted over twelve hours, with its biting cold, forced us to get up more often to pour out our thin water, so the canteen would fill up; not infrequently, we couldn’t hold our urine and would seek an alternative release.

Of course, when I mention other ways, it must be clearly understood: it’s not that there were many choices there, but we found the most practical one in those conditions – that is, we would empty the piss canteen into the cracks between the floorboards. This repeated action, by almost all the prisoners, for years and years, had turned the room into a horse stable, where the stench of rotted wood and preserved urine reeked.

Along with the foul smell, germs would spread, and as a result, it was rare for a prisoner to escape infectious diseases. This was one more reason to escape as soon as possible from that boat sailing on a sea of piss. As I mentioned above, crowded behind the door, anxiously, we waited for our turn.

More than once it happened that our urine, or even our solid waste, escaped into our pants behind the door before it was opened. Therefore, everyone had invented some small, original trick, for example, to fake being seriously ill, to foam from intestinal pains, to strain from diarrhea, etc., in order to get service a little faster.

But this method wasn’t always guaranteed to succeed, because the internal service police officers had also gotten used to our tricks and were not impressed by such games. And when it really happened that a prisoner was in a critical condition, they would let him writhe in piercing pain, and what’s worse, they would sometimes mistake him for a professional faker, and the poor guy would see himself getting handcuffed. In the end, he had no choice but to get covered from head to toe in his own filth.

So, depending on the guard, we would improvise the next game. For example, when Seit Bardhi, from “Tirona,” was on duty, no one would make a sound, because we knew what awaited us. When a “big-hearted” one happened to be there, we would sometimes benefit. For example, when we saw Jonuzi or Shefqeti coming, I would take the dancing scarf. I would start howling loudly, so much that the roof tiles would tremble, and they, like patriots of mine, would come and open the door for us. In fact, so as not to be obvious, they themselves had taught me to fake such a farce.

But that morning, it was neither one nor the other, so the trick didn’t work, and we had to wait for our turn to approach.

“Hey, Çim, for Christ’s sake, are you listening to me?”

“Yes, Bixh!” I said aloud, but my mind was wandering somewhere else.

“I had a strange dream, you know!”

“What did you see, Bixh?!”

“Two big goats came to me and spoke to me like they were people! I swear to Allah, I swear to God!” Luigji swore repeatedly and shook me by the arm. I didn’t want to extinguish the hopes he had pinned on his dreams, even though he often daydreamed in the middle of the day.

“Okay, Luigj, I believe you! But what happened?” I feigned interest, so he would talk, to pass those few minutes until they opened the door for us.

“I swear, we’re gonna leave today! I spoke with the Great One, you know!” he fixed his round eyes, like those of a peaceful bird, right on my eyeballs. “May seven hundred devils eat me if I’m lying!” he added and rubbed his paws.

“You don’t have to swear, man, of course I believe you!” I said, pretending to be a confidant.

We got used to his type; he was harmlessly naive, not dangerous, half-witted. His whole world, like a closed circuit, came down to eating; it started with bread and ended right there, with bread. He was, so to speak, the most prominent prototype of a species that lived only to eat. This poor guy, he connected everything to his stomach, as if his brains were in his stomach and his stomach in his head!

Naturally, hunger prevailed there. The prisoners were under a millstone that squeezed and ground them; on one side, hunger gnawed at you, on the other, violence crushed you, and both together negatively influenced everyone’s consciousness.

But while the more responsible ones experienced the lack of food as a physiological deficiency that forced them to concentrate all their mental and spiritual strength to reason about the circumstances and the catastrophic state they had been reduced to (so that even under the destructive effects of hunger and violence, they would find opportunities for moral and physical resistance, to save what could be saved), the opposite happened with the category of the miserable, who would give up everything in exchange for a benefit.

Every morning, Luigji would wake up in a stupor from the variety of foods that appeared to him in his sleep. As soon as he started talking, he would ramble on and on until he would come back to bread. I understood it right. This insatiable simpleton, who had grown up with an empty belly at the doors of the world, represented the man-animal. But what surprised me was the fact that they could sentence such a simpleton for political reasons, a man with a below-average intellect?!

However, this dilemma would only bother me at first, because later, I would get to know many others, in a much more serious psychological state than Luigji.

“You know, Çim? The second thing that appeared to me was a big dish, full of halva! I ate, and I ate, until I was full!” He was silent for a moment, then… “Are you listening to me, man?” When he realized that my mind had flown elsewhere, he shook me hard.

Although I pretended to be listening to him carefully, my mind was elsewhere, outside the walls of the cell.

“Hold on, Bixh, you’re breaking me, man! And besides, as far as I know, they serve halva for the dead!” I interrupted him with a laugh.

“Yeah, man, that’s exactly how it is! But in dreams, things go backward!” he explained to me seriously.

“Bixho, you’re the luckiest of all the lucky ones! You lie down without eating, and you get up with a full stomach! But, when you wake up… a-ah, me too!” Ladi mocked and, with his hand, imitated a violin bow over strings.

“So, man of the earth, I’ve never gotten full when I’m awake, and I get bloated in my sleep, but you’re worse off than me, you don’t get full when you’re awake or when you’re asleep!” Luigji retorted, quick as a flash. “But today, you’ll see, my dream is gonna come true!” he added, self-assured.

“We’re on the same page, Bixh!” I agreed to please him.

In fact, I didn’t think that at all, but how could we get through the days without Luigji’s nonsense? While we were talking, it was our turn to go to the bathroom and get some air. Each of us grabbed our water and urine canteens and rushed outside.

We went to the single bathroom in turn and headed to the aeration cell, which was waiting for us, especially with its door open. Inside that four-square-meter circle, everyone began the movements they thought were most beneficial for their body. We limbered up, as much as a stiff person can.

Meanwhile, the flapping of slippers died out. It was understood, they had finished taking all the prisoners outside. Now the opposite ritual began, that is, the return to the inner cells. However, this was also done according to the same rule; whoever they had taken out first, they would put in first, and so on. So, we still had a little time available to enjoy the clean air.

That day, they broke the rule. When it was the turn of one of the cells before ours, the policeman bypassed it, he didn’t open the door, and no one from inside made a sound. Naturally, no one would utter a word when it came to staying a little longer in the fresh air, because no one was given the chance to do it again. And when it was our turn, they didn’t open the door either.

“Looks like they’ve become kind-hearted, they’re letting us enjoy the fresh, sub-zero air!” Ladi rejoiced.

“Oh, Çim, didn’t I tell you?!” Luigji burst out.

“Phew, you say so many things, Bixh! How can I remember what you’ve told me?”

“I swear to God, they’re gonna send us away, right now!” Luigji braced himself and gave Ladi a challenging look.

“You are, Bixh!” I agreed.

But Ladi couldn’t take the challenge:

“Hey Bixh, are you gonna be a simpleton your whole life, you miserable wretch! Are you still daydreaming now?!”

“You’ll see! You’ll see!” Luigji insisted.

“What are we gonna see, you simpleton? The handcuffs?!”

“We’re gonna leave right now, I swear!” and Bixhi made the sign of the cross.

“They’re gonna disinfect our cell with Koçifos, you fool! You’ve brought all the fleas in the world here!” Ladi taunted him with this mournful song from Labëria.

“Come on, man! When they brought me here with you, I found you two, along with all your fleas!” Luigji defended himself, offended.

Then, he strained his ears to catch the sound of the latches opening and closing and added:

“See, see, we’re gonna go!” He reinforced his thought by rubbing his hands more forcefully than ever.

“Of course we’re gonna go, ’cause the beans with mouse meat are waiting for us!” Ladi tried to extend the game.

“Oh no, Mom, I’m dying for a piece of bread!” Bixhi began his daily complaint when he heard food being mentioned.

“Hang in there, Bixh! Because for sure, where they’re taking us, trays of pilaf and halva are waiting!” I consoled him.

“I don’t know where we’re gonna end up, men, but it’s gonna be better than here!”

“Without a doubt!” I reinforced it.

“Or at least, we’ll get full!” he vented to the sky with a deep sigh: “Uf-f-f, oh Jesus!” He followed it with the sign of the cross and bowed his big head.

“Hang in there, Bixh! We’ll definitely get full, someday!” I stimulated his gastronomic senses.

“Wherever we go, just not in a cell! There will be other people there, and they’ll give us something! I swear to the Great One, we’ll be how God wants us to be!” He made the sign of the cross again and continued his monologue.

He couldn’t hold on any longer; he had mounted Bacchus’s back and was sailing over the crossed irons, beyond the cold walls of the cell, toward some flying trays, stuffed with rice and beef bones. The simpleton was trying to fill his empty belly…!

Eventually, the latch screeched, and our door opened. A few steps away, three shaven-headed men, their skin faded from the long stay in the darkness of the cell, stood startled. They were terribly pale, weak, exhausted; their dry legs could barely hold them up. It seemed they hadn’t been hit by a ray of sun for a long time, because all three blinked their eyes like chickens with the flu. The first one was taller, the second was a little rounder but still bony, while the third was short and skeletal.

After so many months, it was the first time I faced other prisoners, besides those I had shared a cell with. I went straight toward them, my eyes fixed on their unfamiliar faces. Without getting too close, it seemed to me that I had met two of them somewhere. But where? Under what circumstances? I couldn’t remember?! The cell had tangled my thoughts.

I struggled to recall the people I had met in my life, but it was fruitless. I had indeed fixed those two faces in my mind, maybe I had even talked with them; still, no detail became clear.

“Where could I have seen them?” I was torturing myself, when at that moment; the skeletal one formed a slight smile, which in the corner of his grimacing mouth, on his upper jaw, revealed a jackal-like tooth. “Nika”?! This exclamation escaped from me at once.

“Yes, man, it’s me!” the other one affirmed.

“Stop the chatter!” the policeman interrupted us before we had even started, and ordered: “Get your rags ready, you’re leaving right now!”

“Hooray, hooray – a…”! Luigji burst into prolonged cheers, and a few sparks of triumph flashed in his eyes.

He rushed at me, threw his long, chimpanzee-like arms around me, almost suffocating me.

“Didn’t I tell you, huh, didn’t I tell you?!” he chirped in my ear and jumped, unable to wait to leave these scabrous holes behind, which had hollowed out a cave in his stomach.

They returned us to our cell. They ordered us to get our rags ready, which I can say we had none of (Ladi and Luigji had neither a mattress nor a blanket, just two torn blankets, which they would leave where they found them).

We only gathered mine and sat down, the three of us, on my rolled-up mattress. In silence, we wondered where we might end up. No one spoke, because no one could imagine the HELL that awaited us. Not even Luigji, who was generally known for his wild imagination, uttered a word.

“Where are they taking us?” I asked pointlessly, just to break the silence.

“The devil knows! If even Bixhi doesn’t have a clue, how would the rest of us know?!” Ladi replied, his eyes fixed on Luigji.

“Well, I swear to God, they’re gonna take us somewhere, men!” Luigji played the prophet.

“But where, man?”

“To Tirana, to Skrofotina in Vlora, to Burrel prison, to Spaç, to hell and back, just not here!” he continued his prophecy.

But it was only guesswork, endless guessing! One would guess here, the other there, but it remained fantasy and only fantasy. Taking advantage of the long moments when we racked our brains to imagine the HELL that awaited us, and which no one could guess, I will give a brief description of it, as I found it the day I arrived there, at the Reps prison camp. Memorie.al