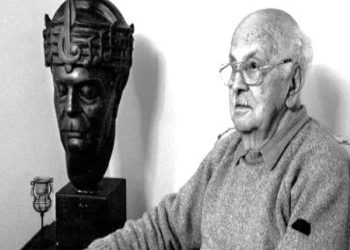

Memorie.al / It weren’t difficult to find the scion of the Frashëri family, as suggested by the reader Përparim Skënderi. The secret wasn’t so much in his famous lineage, as Mehmet Frashëri, but rather in the strange pseudonym for a man approaching his 90s: Pipi. All his life, he had been called by this affectionate name, given to him by his aunt who was educated in France, so much so that… it was forgotten that his name was Mehmet Frashëri. Forgotten by the neighborhood, friends, and relatives, but not by… the State Security. For 45 years under the communist system, he was persecuted in the vilest ways as a descendant of beys, while high-ranking state officials defended their theses with the fact that the Frashëri family sold their wealth to fight for a free Albania.

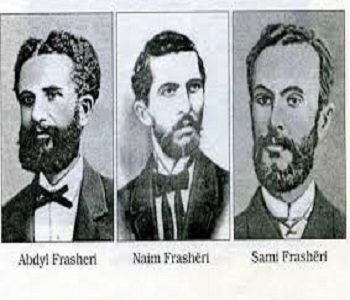

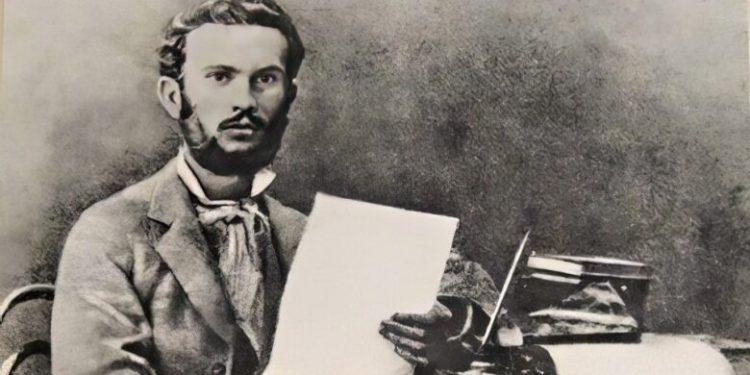

He was not given any kind of job, despite knowing two foreign languages perfectly, and despite the fact that an entire era of literature, the National Renaissance, was identified by the names of his uncles: Abdyl, Sami, and Naim. Mehmet Frashëri’s children were denied the right to study despite their excellent results, while children in schools were taught “Pastoral Life and Agriculture” by his uncle Naim.

You can find Pipi every morning at 9:00 AM at the nondescript pub across from his house on “Qemal Stafa” street. He absolutely has to be there because he drinks his daily “ration” of “Grapa” raki. “It’s good for my heart. If I were Veseli, I’d smoke too. Just one small glass every morning, I don’t overdo it,” Pipi says, inviting us to sit down as if we were “family.” He doesn’t take off his dark, brown glasses, and despite being in a chair, he holds on to a cane.

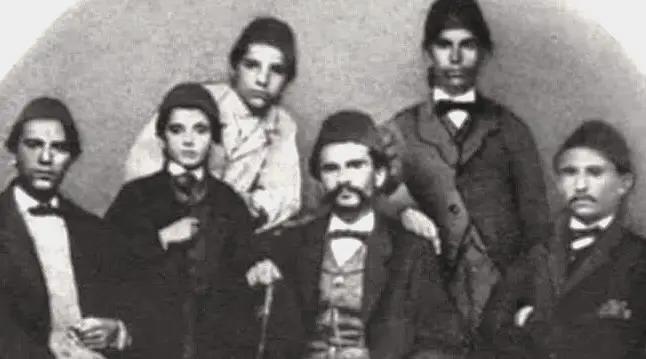

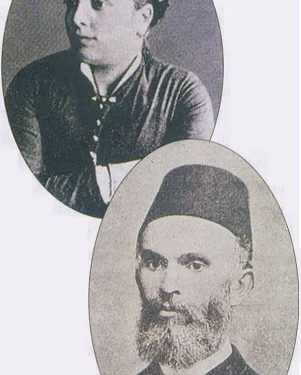

Pipi is the only male scion of the great patriotic Frashëri family, who inherited the name of his grandfather, Mehmet. Talking about his family tree, he clarifies: “My great-grandparents, Halit and Emine, had 6 brothers and 2 sisters. The first of these was Abdyl, who had 2 sons, but neither of them married. So, he had no descendants. Then there was the eldest daughter, Nafisa, but I don’t even have a photo of her and nothing accurate is known about her anywhere. After her was Sherif, who unfortunately died at a very young age. However, Sherif left behind one daughter, Asia. Asia was adopted by Naim. Naim also had another daughter. Again, no son…! After Naim came the other sister, Shahnisha. She married Ibrahim Pasha Vërzheshta, a military doctor. Shahnisha, after marrying, went to live in Turkey and nothing was ever heard about her. In order, we come to Sami, who also only had a daughter as his heir. The males were further reduced in the Frashëri family with the rapid death of the other brother, Tahsim. The seventh in line, Tahsim, was very talented in the field of literature and philosophy but died at just 27 years old. Now we come to the last son, from whom I got my name, my grandfather, Mehmet. He had an only son, Hysref, my father. Likewise, my father only had me as a son and three daughters. Since I was the only male among all these descendants, he decided to preserve the legacy by leaving me the name of my grandfather, Mehmet.”

Pipi shares every detail about his family with photos. The genealogy album is missing two photos: that of his great-grandmother Emine and her eldest daughter, Nafisa. This is because, at that time, women did not often appear in photos, and above all, it was difficult to find a photographer.

After finishing his account of the family tree, Pipi moves on to himself, although it’s difficult to get him to talk. “I have a lot of bad memories, so I don’t go back to the past, but I deal with the present,” he says, while recounting fragments of his life, from what happened to him with the Agrarian Reform in Albania. The great surname he was always proud of began to persecute him. But it wasn’t only the Frashëri surname that persecuted Pipi.

He also had another “blemish” of inheritance. He was a descendant of the Toptani family. When his grandfather was in prison during the Austro-Hungarian period, he met Murat Toptani. Since they had become very close friends, they decided to make an “exchange.” Murat gave his sister to Mehmet as a wife (Pipi’s grandmother), while he himself married Naim’s adopted daughter (the daughter of his deceased brother, Sherif), Asia.

So, Pipi inherited endless properties from both parents and was ranked among the largest beys in Albania. Meanwhile, he had a beautiful house in the center of Tirana, on what is now “Qemal Stafa” street. All of Pipi’s wealth was “buried” in 1945, never to be recovered, despite the arrival of democracy. “They took everything from us. The properties, we knew that would happen and we accepted it out of hardship, but they also took our house, putting others there, even though we had sheltered dozens of partisans during the war. They forgot all our good deeds, the contribution of my uncles, and only remembered the fact that we were a family of beys. As kulaks, which they labeled us, they left us only an old shack next to the big house, which had always been used for coal or even livestock. For half a century, I lived there with my family, in the cold, almost without work, enduring contempt and hatred that I don’t know where it came from. This hatred went so far that they even took my suit, because they had already devoured the mattresses and quilts. It’s strange, but the very people I had grown up with, had collaborated with during the war, or had eaten bread in my house, turned against me,” the old Frashëri man recounts. According to him, even though he was one of the few who had studied and knew foreign languages at a time when Albania suffered from illiteracy and needed teachers, he was never accepted to be part of the education campaign, despite his many requests.

Not only that, but Pipi was not accepted for ordinary or mundane jobs. With his remaining friendships, he would occasionally find a job as a painter, until his talent as a designer and the need for such a profession managed to get him a job as a decorator in the village of Tërshajë in Tirana. And Pipi says they gave him this opportunity out of need, because he was very skilled at designing shops and maps, and not out of generosity.

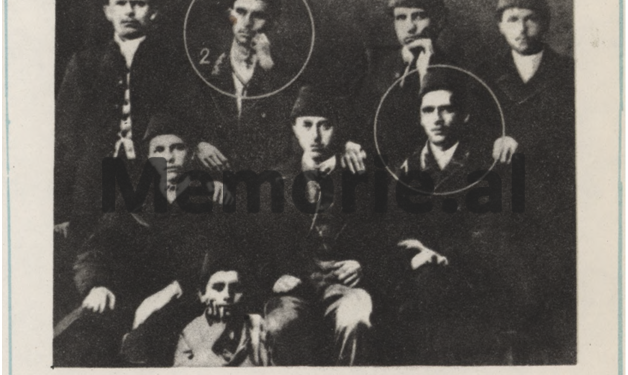

Despite the fact that, year after year, his real name had been forgotten and everyone knew him as Pipi, the joy of a secure job would not last long. Someone had remembered that he was Mehmet Frashëri…! It was Sami’s own grandson from his daughter, named Eminereji. Born and raised in Turkey, he had remembered his relatives and had learned that the male heir was in Tirana.

Eminereji had requested a visit to Tirana in 1974, on which occasion he would bring the remains of two of his uncles, Naim and Abdyl, to Albania, but not Sami’s, which the Turkish state had refused to allow to be moved. Many “fake” Frashëri family members appeared at the reburial. The real one had been kept away, until the moment Eminereji insisted on meeting him, as he would leave urgently the next day. “Someone from the neighborhood came to me and told me that I was wanted at the Central Committee. I got scared because I had barely found a job and I thought who knows what awaits me this time. I took a friend of mine with the last name Arbana, who was with the Sigurimi, and I started heading there, where they told me to go to Hotel ‘Dajti’ to meet Eminereji. I did as they told me. Eminereji welcomed me very well and kept asking me what I needed, how I was doing, if the state respected me, and so on. And I said ‘yes,’ ‘yes’ to everything, without telling him anything close to the truth. Convinced that it was as I told him, Eminereji had to leave very quickly as he was heading to Turkey. After this meeting, my hours of anxiety began. Again at the Central Committee…! But it turned out completely different. I remember it like it was yesterday. It was room 3, on the second floor. A man was sitting there waiting for me, with glasses, and another was standing. I told them who I was and they told me to sit down. ‘Good for you! You’ve shown yourself to be a man, we didn’t expect it!’ I was speechless, then I realized they knew the whole conversation I had with Eminereji. They even thanked me for not having told him anything and for this ‘sign of loyalty to the party,’ as they from the Central Committee called it. They asked me what I wished for. And I only asked for a job, for my wife and my sons. What more could I want?!” Pipi recounts, not forgetting to occasionally lift his glass of “Grapa.”

Even today, after decades, Pipi doesn’t want more. He hasn’t even bothered to ask for the many properties confiscated back in 1945. “Why should I ask?! It’s known that properties will never be returned in Albania. There’s no law or authority that will lead the owner back to his land. On top of my properties, politicians’ palaces have been built, from Kamza, to Central Albania, all the way to Përmet. Others have been forcibly seized from me, and I know it’s useless to deal with this. What’s gone is gone forever, just like my years. I don’t intend to spend my small old-age pension on photocopying papers, considering that with that money I can very well buy the medicine that strengthens my heart. I’ve also told my children not to chase after papers. I’ll repeat it: Properties will never be returned in Albania,” the largest heir of properties in the Cadastre insists, but the owner of only a few square meters in his daily life. What remains of his great surname are only the bitter memories of 50 years, the house he reclaimed after the 90s, and a photo album…! / Memorie.al