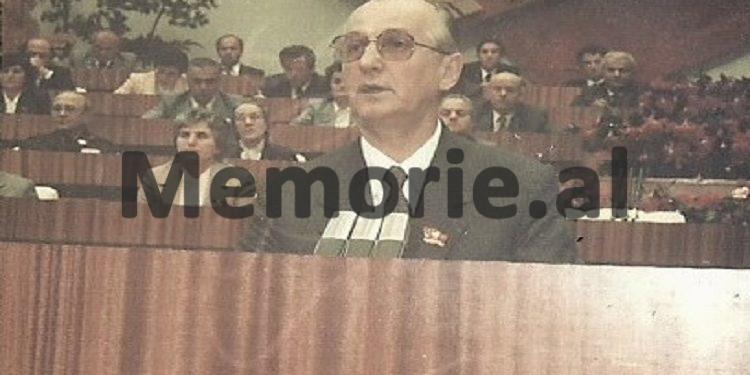

Memorie.al / As the dictator Hoxha had just died in Albania, it seemed that the West, and more specifically its press and media, were becoming more interested in what was happening and what would happen next in the small communist-Stalinist country. While the enigma of who would be Hoxha’s successor had been solved for some time, it now seemed that the first results were expected from him, and he was being evaluated by them as the most effective ruler Albania had had since Hoxha had disappeared from the public scene.

A rapprochement with the West had begun even before Hoxha’s death, and this had not gone unnoticed by the Western press. But a series of dilemmas still remained open. For example, what would happen now with the small Stalinist country? Would it get closer to the Soviet Union or the West? Who was Ramiz Alia really, and how many supporters did he have in the Politburo? Had he brought a new spirit, especially after the 9th Congress of the Party of Labor, and did he intend to carry out stable economic and political reforms, however small, that would thus make it possible for the country to get closer to the West and the outside world?

The increase in diplomatic relations with the world was already an evident fact, as was the “determination” not to establish relations with the US and the Soviet Union. While the signing of several trade agreements with regional and Western countries is noted, the doubt is raised that if the opening to the world does not continue, the Albanian economy is destined to remain stagnant and go bankrupt. “People, however, are no longer so isolated from the foreign world. Their main contact with the West comes from foreign radios and TV channels. Young people wear ‘blue-jeans’ and Italian glasses.”

This was the atmosphere full of anxiety, but at the same time full of hope for post-Enverist Albania, which now seemed to have left behind a long dictatorial history and was trying to break away, at least economically. “Economic self-reliance has gone hand in hand with militant nationalism. Starting in the early ’60s, Albania began building bunkers with a small window, just big enough to stick a rifle barrel out of—the result of a defense campaign initiated and inspired by Hoxha, who trumpeted the constant threat of a Western and Eastern invasion of his country.”

These and many other things, then, were what was presented in the two articles of TIME magazine, dated April 22, 1985, and December 1, 1986, respectively, where from one to the other, one feels, so to speak, the “hope of change,” even though not much time had passed since the death of Enver Hoxha.

Returning to the events in retrospect, in the first TIME article, a few days after Hoxha’s death on April 11, 1985, we find, of course, a brief and general description of Enver Hoxha’s life and political career, before moving on to the presentation of the post-Hoxha situation in Albania and the hopes for a more open policy towards the outside world.

There we also learn of Albania’s refusal to reconnect or improve relations with the Soviet Union, by rejecting the official telegram of condolences for the death of the Albanian dictator. Moreover, the article in question also casts a shadow of doubt on the (self-) suicide of Mehmet Shehu.

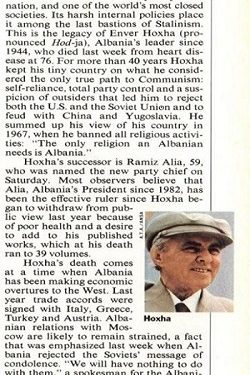

Albania, an isolated mountainous country with 2.9 million inhabitants, is a country of dark statistics. It is the poorest nation in Europe and one of the most closed societies in the world. It is the country of harsh internal politics and one of the last Stalinist bastions in the world. This is the legacy of Enver Hoxha, the leader of Albania since 1944, who died last week of a heart attack at the age of 76.

For more than 40 years, Hoxha kept his small country on what he considered to be the “true communism” line: self-reliance, complete party control, and suspicion of foreigners were the reasons that led him to reject both America and the Soviet Union, and also to cool down relations with China and Yugoslavia to the maximum.

He fulfilled his complete vision of what he intended to do with his country in 1967, when he stopped all religious activities in the country: “The only religion that Albania now needed was the Party and Albania.”

Hoxha’s successor is Ramiz Alia, 59, who was appointed head of the party, as its new secretary, last Saturday. Many observers believe that Alia, the President of Albania since 1982, has been the most effective ruler since Hoxha began to disappear from public appearances last year, due to poor health and the desire to add more to his written works, which, after his death, now reach the figure of 39 volumes.

Hoxha’s death comes at a time when Albania has made progress in reviewing economic relations with the West. Last year, trade agreements were signed with Italy, Greece, and Turkey, as well as with Austria. Albania’s relations with Moscow are very likely to remain tense, a fact that was also highlighted last week when Albania rejected a message of condolences from the Soviets.

“We have nothing to do with them,” said a spokesman for the Albanian embassy in Vienna to the “Reuters” agency. Enver Hoxha broke off relations with Moscow after Nikita Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization efforts in the early ’60s. He later accepted economic aid of $5 billion from China, but this connection was also extinguished in 1972, after China improved its relations with the US.

Hoxha, a product of a middle-class Muslim family and educated in France, came to power as the head of the partisan resistance movement against the Germans and Italians during the Second World War. He led Albania with an iron fist, sending tens of thousands of people to forced labor camps. He tolerated no political opposition in the country, and his rivals were continuously eliminated, including Prime Minister Shehu, his closest collaborator.

Mehmet Shehu was officially reported to have committed suicide in December 1981, but it is widely rumored that Hoxha was the one who killed him, because he had sought stronger ties with the West, which Hoxha had then opposed. / Memorie.al

(Adapted from “Time – magazine,” Monday, April 22, 1985)